People have always been more fascinated by bad news than good. Drive on the highway and there’s a crash, the likelihood of looking at the wreckage is inevitable. There’s something out of ordinary about the destruction and death if you don’t witness it every day, which quickly turns into boredom and acedia.

Living a fairly comfortable life allows people to sift through the news, which is rarely positive. This is true especially today. Not only are we living through the age of high anxiety but also high distraction. Yet, is there anything new about predicament? Apart from being able to “carry the internet” with us everywhere, we’re still the same creatures of habitual doom-seeking.

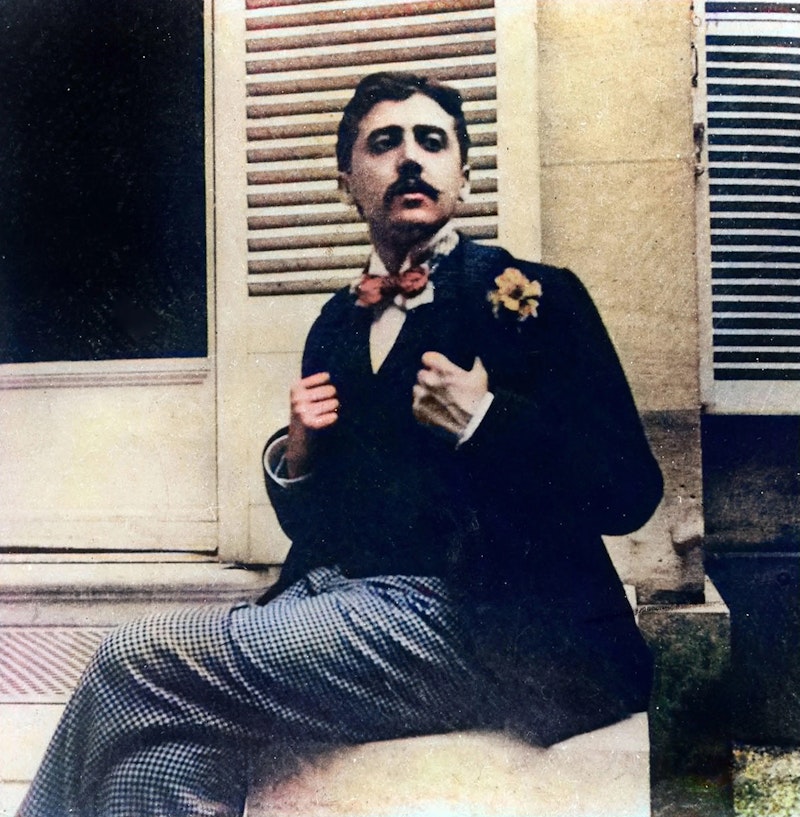

Marcel Proust, a writer who reveled in grainy details of one’s life, found a daily dose of bad news both disgusting and intriguing. On this subject, Proust wrote, “The abominable and sensual act called reading the newspaper, thanks to which all the misfortunes and cataclysms in the universe over the last twenty-four hours, the battles which cost the lives of fifty-thousand men, the murders, the strikes, the bankruptcies, the fires, the poisonings, the suicides, the divorces, the cruel emotions of statesmen and actors, are transformed for us, who don’t even care, into a morning treat, blending in wonderfully, in a particularly exciting and tonic way, with the recommended ingestion of a few sips of café au lait.”

There’s always another catastrophe or the end of the world that has been averted. Our concern is oriented toward death: denial, fear, obsession. Most people don’t embrace going toward the Nietzschean edge, yet couldn’t an obsession with “the end” be construed as a way of seeking a path of destruction.

Earlier, I mentioned that we have become a society of high distraction. I write “high” because we essentially carry computers with us, whipping them out as soon as we find ourselves faced with solitude. I don’t think that is an unusually serious existential issue. Rather, it’s mostly a question of habit, which (as most people can attest to) can be easily changed with some willpower.

The question we ought to ask is how do we see and value (our) time? This was also Proust’s concern who penned thousands of pages on memory and passage of time. Proust’s point, if there is such a thing in his aesthetically charged meditations on time, is that life must be noticed, or else it’s not life at all.

Proust took his time. His attention to detail is not to everyone’s tastes. When Proust tried publishing his work, one of the publishers remarked, “…I fail to see why a chap needs thirty pages to describe how he tosses and turns in bed before falling asleep.”

Most people are inclined to agree with this sentiment. Get on with it already! We have things to do! We have no time for this nonsense! Aesthetically speaking, not everyone would choose to read Proust’s long ruminations. But that’s less significant than what Proust’s literary output signifies, the importance of memory.

In a recent interview for Palladium, novelist Walter Kirn said something very important in regard to the current predicament of distraction and negation of time itself.

“If you want to throw off the ballast of the past,” says Kirn, “in order to be more responsive to the present, there’s a logical next step which is to be no longer loyal to the present—to exist in a constant state of anticipation—such that one does not even form memories to get attached to! You don’t bond with the present because you’ve learned that it’s about to become the past, and the past is a bad thing, and memories only hold you back, so why even form them? Why even have experiences? Because if I have an experience that lodges deeply enough in me, it will turn into a memory and it will hold me back.”

There’s a price to pay for this, and Kirn understands that with the mind of an artist and philosopher. He continues, “As a dramatist, I can tell you that without memory, you don’t even have a story. Unless Othello remembers what it was like when he first saw Desdemona and fell in love with her, then Iago’s attempt to get him to distrust her is meaningless. Unless the temptation to see her as deceptive is posed against an earlier honeymoon period, it has no meaning. When you live perpetually slightly ahead of the present, never bonding, never settling down, never letting yourself be penetrated—even by experience let alone memories to hang onto—you are a digital bit of information to be formed into anything. You volunteered for it!”

Kirn, like Proust, is in many ways asking us to notice life. Not in any sentimental or that awful “live, laugh, love” way but in accepting the uncertainty of the future with a constant “remembrance of things past.” What better way to feel like an embodied human being than to know that there were others before we came, and that today is the only worry we can handle.