It has sometimes occurred to people in my former line of work (philosophy professor) to wonder what a name is. For example, is a name a noun? A noun is supposed to be any word that picks out a "person, place, or thing." But there are cases where nouns behave strangely or it's not certain whether we're dealing with a noun or not. Consider the new use of the pronoun “them,” for example. On any particular occasion of use, it picks out a particular person, but in general there is no particular person to whom “them” (or “her”) refers uniquely; it refers to all particular persons equally, but one at a time, which is not how nouns like “person” behave. Or it refers to whomever one is pointing at, which is a weird noun indeed.

“Crispin Sartwell,” however, doesn’t refer to whomever one is pointing at. If you're pointing at someone other than me and saying “Crispin Sartwell,” you’re making a mistake. It's like my very own noun, a noun I possess or that possesses me, that designates and encompasses me. But it's also a handle that other people can grab: "Crispin! Get your ass over here." "Crispin Sartwell, we wish to notify you that your payment is delinquent." My name picks me out and distinguishes me from the likes of you: like a prize or a felony conviction. Without names of some sort, prizes and felony convictions would be impossible.

I've heard many people say that they dislike or even hate their own names, and I've known people to change their names or insist on being designated exclusively by a middle name or a nickname for various reasons: a fallout with their family of origin, for example, or a gender transition, or just a sense of mismatch between name and reality.

This is hard to figure out: Why and how and in what respect a name, perhaps found in a "what to name the baby" book or on a website, seemingly chosen arbitrarily, can come to feel like an identity, an essence, or some sort of description, maybe appropriate, maybe misleading. “Robert” and for that matter “Crispin” have no particular content; they don't attribute any character to anybody.

And yet it could be felt as a mistake to be named “Robert.” Maybe Robert, the man, doesn't "feel like a Robert." Is that like the fact that Robert’s an accountant, but he doesn't feel like an accountant, or that Robert is 70 but doesn't feel that old, or that Robert "doesn't feel like himself today"? It sounds like that last one, but maybe he's feeling just like himself; it's just that feeling like himself is not feeling like a Robert. No idea what that can mean, really, but I manifest a version of the same puzzle: I feel so much like a Crispin that I don't think I’d ever change my name. I can't think of myself otherwise than as the thing “Crispin Sartwell” dangles from like a tag. But I also can't say what “feeling like Crispin” involves.

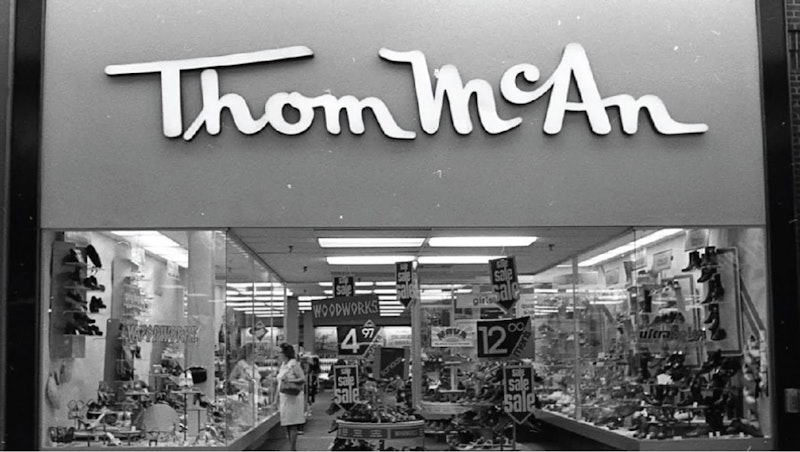

I think it was a bold move for my parents to give me such an unusual name, which they claimed they got out Shakespeare (the Battle of Agincourt is portrayed in the bard's Henry V as occurring on "St. Crispin's Day"). That Crispin was the patron saint of cobblers was probably not a factor, since my parents were atheists who bought their shoes at Thom McAn.

My dad told me that it came down to “Crispin” or “Alaric” (after the first barbarian to sack Rome) which had in common that the person thus named could choose the very unusual full version, or just shorten to “Cris” or “Al” and no one the wiser. My father did call me “Alaric” from time to time, including in print as he wrote under pseudonyms about raising his kids. As a teenager, Ithought being named after a brutal Visigoth Rome-sacker would’ve been cool. But when you get down to it, “Alaric” is pretty weird.

If “Crispin” is also weird, it's my very own weirdness. I love my name. I love that it's unusual. I wasn't worried that “crispinsartwell@gmail.com” was already taken, for there is (I’m confident) only one Crispin Sartwell in the world, perhaps only one Crispin Sartwell in the world's history. That's me, bubba!

I know that here are other Crispins here and there, especially in England, such as the actor Crispin Glover and the philosopher Crispin Wright. My slogan for awhile in philosophy was "I'm not Wright, but I'm not wrong." Meanwhile my grad school professor Jim Cargile relentlessly referred to me as “Jean-Paul Sartwell.” But I've never actually met another Crispin. It's true people made fun of my name when I was a kid, but it seemed pretty okay and affectionate because it always broke down to “Crispy.” Many people over many years called me “Crispy Critters,” for example, after an unaccountably popular cereal brand. As insulting nicknames go, how bad is “Crispy Critters”?

Hell yeah I'm Crispy. I'm the blues harmonica player known as Little Crispy. My prose is crispy as hell. If your stuff ain't crispy, don't bring it around here, you soggy motherfuckers.

Anyway, I can't imagine myself without this name and I don't want to. I have the sense that this name affected the arc of my life in some way, or maybe the factors that led me to get this name also led me to a situation in which I seem to disagree with almost everyone about almost everything. I'm Crispin, y'all, and that's very unusual! I'm really not like y'all, or else my name would be “Robert” or something. Okay, maybe occasionally I could wish for that.

I can hardly imagine what it would be like to have a common name. But why do I feel that, and do names have any effect on lives? It's hard to see how they can, but hard not to feel that they do. I feel if I had a more common name, I'd be less unique as a person. Even philosophers have thought that names are fundamental. And speaking of saints, Augustine argued that all language and all communication was a kind of naming.

But the idea that names make fates seems like raw magic or superstition, the kind that teaches that you can control a person if you know their true name. Well if one can be controlled by one's true name, I’m in trouble, because my true name, my prize and my felony conviction, is right there on the byline.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on X: @CrispinSartwell