Jean Luc-Godard would probably give a smug chuckle at the subtitle of Richard Brody’s new biography, and not only because, insofar as Brody depicts him, he’s as pompous as the day is long. But he would also laugh from the presumed redundancy in the phrase “working life.” For Godard, his work was his life; nearly every one of his many films were a direct outgrowth of a personal relationship or experience, and his most famous collaborators, most of whom eventually became enemies, were his wives and good friends. When parsing the man’s considerable filmography, Brody connects the dots between Godard’s personal relationships and his increasingly theory-addled movies with an acute scholar’s eye. But while a man’s work may be his life and vice versa, neither form the entirety of the man, and Brody’s Godard never comes into focus as a narrative protagonist.

“Jean-Luc Godard is an artist as dominant, as crucial, as protean, and as influential as Picasso,” Brody says in his preface, “but he is a Picasso who vanished from public consciousness and from the encyclopedias after the first heady flourish of Cubism.” Godard’s own first heady flourishes were spent at the forefront of the Nouvelle Vague, the “French New Wave” of filmmakers who in the early 1960s rebelled against what Godard’s childhood friend and early collaborator François Truffaut dismissively called the “tradition of quality” in French cinema. In the pages of their now-legendary film magazine Cahiers du cinéma they praised the directorial talents of Hollywood directors like Howard Hawks, Otto Preminger, and Alfred Hitchcock, claiming their films were as artfully made as those of established European directors like Jean Renoir. It’s a testament to the Cahiers group’s influence and foresight that these directors’ brilliance is now taken for granted, but at the time the burgeoning French critics were perceived as tasteless pop apologists.

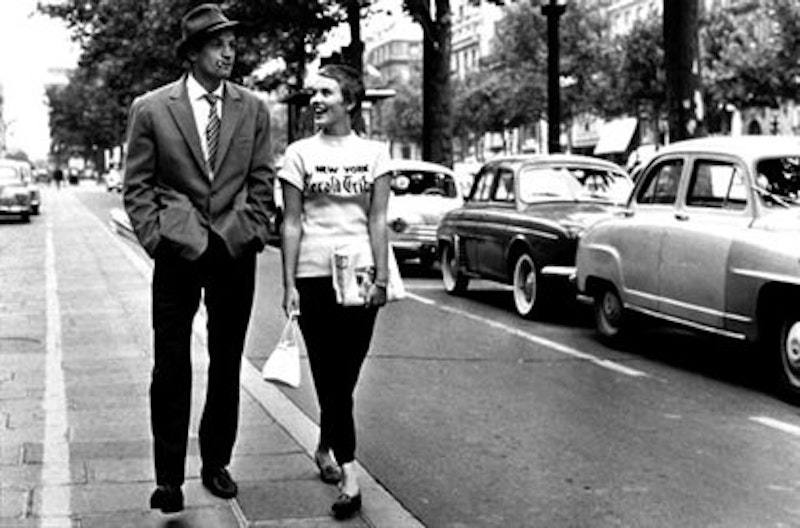

The New Wave group—which also included now-legendary directors like Louis Malle, Agnés Varda, and Eric Rohmer—eventually turned their criticism into original work, and the common consensus is that Truffaut’s The 400 Blows inaugurated the artistic movement upon its release in 1959. But if “The 400 Blows was the setup,” Brody argues, then Godard’s own 1960 debut, Breathless “was the knockout blow.” Truffaut’s film is a gorgeous piece of autobiographical filmmaking, with a revelatory starring turn by 14-year-old Jean-Pierre Leaud as the runaway Antoine Doinel, a role he would reprise in four subsequent Truffaut films over the next 20 years. But Godard’s film, although written by Truffaut, is amazing for its complete rejection of conventional movie language and morality. Its protagonists (Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo, who does for cigarette lip-dangling what Jack Nicholson would later do for eyebrows) are an on-again/off-again young couple who talk about sleeping together and other non-topics. He is a gangster-obsessed hood with a violent criminal streak and she’s an American who sells newspapers on the street. They talk, the police chase him, and eventually he gets gunned down in the middle of Paris—a scene, we learn from Brody’s book, which was filmed in front of unsuspecting Parisians who didn’t know a movie was being made. That’s it for the plot, but the real leading man is Godard himself, who shot and edited the movie with enough verve and spontaneity to match the sharp jazz soundtrack. His obsession with editing led to his greatest technical innovation, cross-cutting, the influence of which can be seen in the American New Hollywood directors of the 1970s, as well as commercials and music videos and nearly every movie since.

Breathless was the beginning of an astonishing artistic run for Godard in which he made 14 films in eight years, many of which are now acknowledged classics: A Woman is a Woman, My Life to Live, Contempt, Band of Outsiders, Alphaville, Pierrot Le Fou, Masculin Féminin, and Weekend among them. About half of these films starred his first wife, Danish-born Anna Karina, who became one of France’s biggest movie stars as a result. Brody does a great job explaining how Godard’s relationship with Karina—which was borderline abusive and in keeping with his lifelong lust for much younger women—affected the films themselves. But while he gives us the journalistic who/what/when/where, we’re never given a clear indication of the basis of Godard’s obsession with Karina. Surely she was beautiful and charming, but those qualities are clear to anyone lucky enough to watch Pierrot Le Fou; it’s still uncertain from Brody’s story why exactly, other than a heightened sense of typical male jealousy, their marriage’s eventual end crushed Godard as it did.

It’s fitting that Brody’s book—and high-profile “Godard in the 60s” series at Manhattan’s Film Forum and Washington, D.C.’s AFI Silver Theater—appear in May 2008, the 40th anniversary of modern Europe’s most politically tumultuous month. Brody never goes so far as to proffer psychological explanations for Godard’s actions, but it’s implicit that he filled the void left by Karina’s absence with an increased attention to radical politics. This allowed him to consort with young French students (the “children of Marx and Coca-Cola” that were the subject of Masculin Féminin) even though he was pushing 40 at the time. He fell in with a group of Maoists at the Sorbonne and eventually exhausted himself with vitriolic anti-American didacticism, all but disappearing from the popular cinematic consciousness for much of the 70s.

From Tout Va Bien (1972)

At this point, about midway through Brody’s book, the main action switches from the crazy energy and esprit de corps of Godard’s New Wave days to his internal conflict about American cinema and politics. There’s a fascinating story to tell here, but Brody maintains his relentless reporter’s style and never fully plumbs the psychological torment that Godard must have felt from the 70s on. Since his initial criticism and films grew directly from his intense love of supposedly disposable American cinema, Godard’s eventual rejection of that country’s politics and culture amounted to a rejection of his own younger tastes and work. By turning his back on American commercialism, he cut ties with the part of himself that created such joyfully anarchic work as Breathless.

Indeed, the progression of Godard’s anti-American rage has the all the overextended illogic of a scorned lover. In his six-hour series Histoire(s) du Cinéma, completed throughout the 90s, he proposed his thesis that cinematic history be divided into two periods: pre-1945, when the art form was honest; and post-1945, when America (and by proxy Hollywood) became the arbiter of cultural taste, subsequently squandering the opportunity to address the concentration camps in an aesthetically honest way. For Godard, no movie properly addressed Auschwitz when it was most necessary, and therefore the art form was doomed. Coupled with his extended exiles in Switzerland and the French countryside, Godard’s later work, while still intellectually vibrant and cinematically fertile, is understandably categorized by an almost pathological aversion to entertaining his audience. The film community responded accordingly, upholding reverence for the landmark 60s work but rarely buying tickets to his new movies. Brody quotes a French journalist from 2004: “It’s as if Godard, between an excess of praise and a lack of love, had disappeared.”

Brody’s book is presented as a hopeful anathema to this disappearance, and he argues, “[Godard’s] more recent films are indeed works of art superior to the early pictures that made his reputation and established his celebrity.” Some of them are incredible, sure (First Name: Carmen is particular self-referential fun for fans of the New Wave films), but artistic “superiority” is an odd term, particularly when the point of comparison is a collection of pictures that are universally considered to be the beginning of modern cinema. Later Godard like For Ever Mozart may be intellectually sophisticated, but you have to watch it with a furrowed brow. It is meant to be understood, whereas the 60s work is meant to be felt.

The technical experiments of Godard’s early work—cross-cutting in Breathless; Contempt’s repetitive music and lack of close-ups; the genre-hopping in Pierrot Le Fou; Masculin Féminin’s title cards and surrealist touches—were all in service of the emotional truths of his characters. These films aren’t “realist” in any formalistic sense, but they are oddly, undeniably affecting and reflect their creator’s intimacy with the entire emotional spectrum. The marriages and romantic relationships in these films are all on the edge of disintegration, and Godard stretches and bends his genres to match. Characters break into song, they strike poses, they address the camera directly, or, in the case of Contempt, they are overwhelmed by the remarkable colors and scenery that Godard packs into his shots.

Brody’s defense of Godard’s later works isn’t a dismissal of the early, of course, and the greater issue with Everything is Cinema is the writing itself. Brody’s depth of research is obvious, and he is an empathetic reader of Godard’s films, but there’s too little insight about the artist himself to justify a 650-page doorstop like this one. Instead, we get the exact particulars of trips to Cannes, point-by-point breakdowns of public sightings, and pages-long plot summaries of every movie in question. Occasionally a fascinating anecdote arises—Godard’s ill-fated collaboration with Norman Mailer for his 1987 version of King Lear is a great sketch in Brody’s telling—but the filmmaker’s motivations and emotions remain entirely distant. Everything is Cinema will be a useful resource for the eventual biographer who reveals the man whose genius birthed modern moviemaking, but for now, Godard remains a mystery.

Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard by Richard Brody. 640 pp., $35, published by Metropolitan Books.