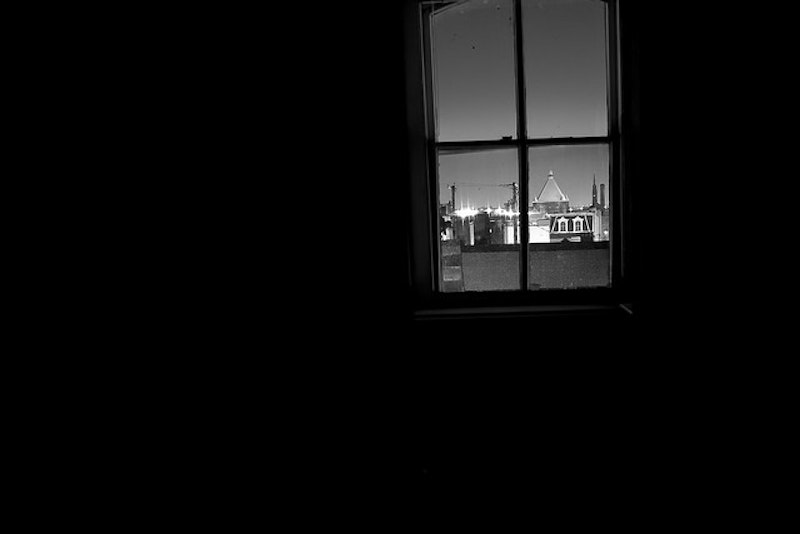

Between the time my father and my mother split, and when my father and my stepmother married, there were three apartments, all in North Baltimore. None were winners, though in retrospect I imagine that winning wasn't necessarily the point. The first two were close to Johns Hopkins University, where my father finished undergrad, though I can only recall the second of these. The window view looked out onto N. Charles St. from a great height and through the stout branches of trees. Inside was an open concept: a large, bright space interrupted by a bathroom, yellow wood floors.

My father parked in a small lot behind the building and to the left, off a one-lane alley that, looking back, could have been safer. The back entrance led through a dilapidated facade of graffiti and peeling paint that stank of baking pizzas, and the implication was that somewhere on that level a pizza parlor was operated, even though we never ate there and I wouldn't have wanted to. Had she seen it, my friend Sanjeevani might have characterized it as "dodgy." You would step into an elevator and rise, incrementally, to classier floors.

I slept on this lame chair that unfolded into a bed; today, I'd balk at those kind of accommodations. My father had me on Thursday evenings and every other weekend; that was the arrangement, the deal. As he unlocked the door one night—there were two or three locks, which seemed excessive and complicated to my mind—I told him that David Schumer, a classmate, claimed to have two birthdays every year, to which my dad, after the briefest consideration, replied that David Schumer was lying to me.

There were the over-spiced burgers Dad made, sans bun, accompanied by pools of corn. He preferred goulash—from which I recoiled—and was partial to store brand sodas mixed with milk or water, which I couldn't comprehend. For grocery shopping he frequented the Rotunda, which was nearby, where we'd see movies and I'd buy comic books with my allowance and where we saw Kurt Schmoke's limousine idling, once. The machine at the Hopkins library where one could buy soda for 35 cents was a wonder—the Styrofoam cup descending, the crushing plop of chopped ice, the ginger ale fizzing rudely to the brim.

The next place, on Green Meadow Parkway, felt less transitional and transitory in that it was subdivided into actual rooms, had a balcony, was on the second floor of a scattered series of two-story units bordering a forest, with a community pool at the center, like a jewel. The woman directly across the hall was always smoking, in a bathrobe; the man whose apartment was beneath hers kept a stack of tires outside of his door for reasons I didn't understand and heard pounding when I ran up the stairs, which was often, and complained bitterly to my father about it, which did nothing to alter my behavior.

Acting on a myth, I baked banana peels in the oven once and then, once they cooled, ate them, and realized that I has been taken. Dad bequeathed me a DOS computer that replaced the series of semi-digital typewriters he'd gifted me over the years, a tool that birthed dozens of zines, which he dutifully photocopied at work on the sly so I could staple them together and mail them to friends who never read them.

I would answer the phone and my father's friends would confuse my voice for his. He found cigarettes I'd purchased and failed to hide adequately and became angrier than I'd ever seen him right before he threw them in the trash. On occasion I accidentally read a heavy Stephen King or Tom Clancy so late into the night that I would put it aside as my alarm sounded, at which point it was time to get up for school. In that same bed, I almost lost my virginity, but it's just as well that I didn't. Reprobates threw their trash into the woods where I wandered aimlessly, got lost, encountered viciously polluted streams, and from these sojourns sprouted poems that I've subsequently disowned but convinced me that I was on the right track, that a muse was leading me somewhere special.