Subject: water riots

Date: Tue, 15 May 2007 12:00:48 -0700

Hello everybody,

I don't have much time so I have to be curt, but recent events have led me to several queries, and I thought I'd share. First a brief synopsis of the incident under discussion, what I call the water riot:

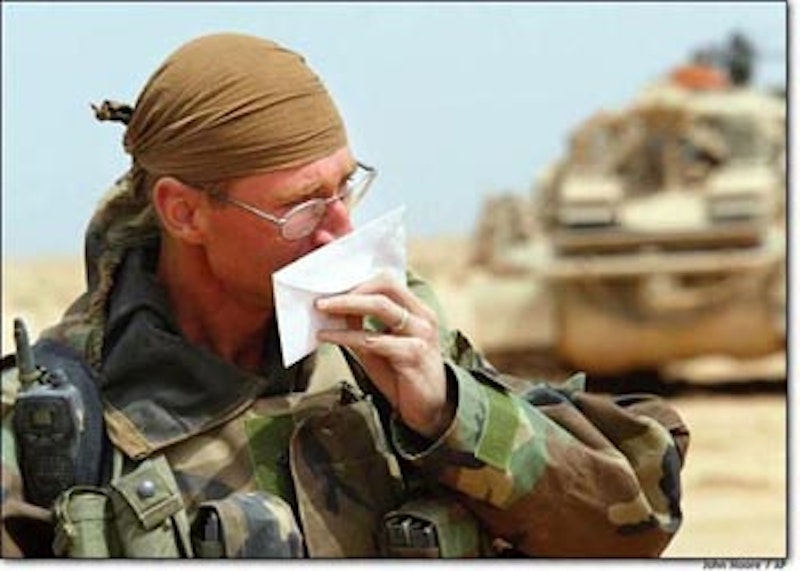

We were to meet a convoy of U.S. military vehicles that were escorting a large number of Iraqi soldiers (members of the fledgling Iraqi Army) in buses. There were several buses and hundreds of Iraqi soldiers. We were to take over the escort of the buses and continue with them to their end point further west (details are deliberately vague).

The approaching convoy was delayed by I.E.D. attacks along the way. Nobody injured, but they were on the road much longer than anticipated. When they arrived we had to re-supply the Iraqis with water before continuing, which we did as expeditiously as military procedure allows (took forever).

The Iraqi soldiers were unruly enough that the water truck necessitated armed guards. A mob of hundreds of soldiers swarmed our cordon and fisticuffs ensued, order was quickly restored without loss of life, maybe some bruises and bloody noses. Water was eventually distributed, convoy continued, the end.

The first and most obvious question this scenario raises is, how close is a self-governing Iraq, devoid of foreign control, when the Iraqi army needs to be escorted from place to place within its own borders? Who actually controls the territory day to day, when heavily armed guards need to quietly whisk the national army from place to place, usually under cover of darkness? Can a case actually be made for a viable exit strategy under these conditions?

Second, is a Western style army, or democracy for that matter, in any way suitable in Iraq? Specific instance: several of the Iraqi soldiers, prior to the water trucks' arrival, vied for preferential treatment (front of the line privileges) because they outranked the majority. Now in American military forces, the ranking personnel make sure the needs of their

subordinates are met before they take anything for themselves. At least they're supposed to, officially, and penalties are in place when they are caught taking advantage, so that any higher-up looking to enjoy first dibs (and they do, a lot) has to be covert and ashamed. There was no shame in the Iraqi leadership, however, when looking to grab water from out their troop's mouths. Privilege and indulgence seem to be viewed here as the frank and

expected fruits of rank or status. Power, then, is to be enjoyed, and not used to public benefit.

In America this is undoubtedly the case as well, happens all the time, the leaders help themselves out as much they can, but with this important difference: it is the reality but not the ideal. Our American ideals lead us to call our leaders "public servants," to sincerely expect them to use their office to their constituent's benefit, and to not elect them unless they at least profess (however superficially) to intend to do so. And if they are caught doing what they always do, they are held accountable, so at least they have to be covert and sneaky and ashamed. No such idealism seems alive in Iraq. The new Shiite government seemed positively surprised when they heard we discouraged reprisals against the Sunni. "We are in power now," they seemed to say, "We finally get to do what's good for us, not everybody."

So who's crazier, the Americans who want lying duplicitous leaders or Iraqis who want honest, selfish ones? Well, the recent historical record shows which system creates less domestic bloodshed, but we Americans consider gloating bad form, too. Finally, and this is just an observation: when we couldn't hold the line without firing into the crowd, we had to start just throwing cases of water into the mob. It meant that the stronger guys would get more, and some might get none, but hey whaddaya want. They fought tooth and nail over the water bottles, I mean elbows and punches and everything, and who wouldn't fight for

something as essential as water in the desert. But two things: one, there was enough water for everybody, if evenly apportioned. Fighting was gratuitous. And two: as they fought they were smiling. It was vicious and violent and a matter of survival, maybe, but most were smiling, like it was good clean sporting fun. Like a rugby match. Make out of those two whatever you can.

Subject: My childlike sense of wonder

Date: Wed, 22 Aug 2007 11:33:31 -0700

I'm not sure anybody is going to find this as funny as I did, because none of you know Cpl. Timbrook as I do, and the better you know him the funnier this is. I will attempt, however, to briefly illustrate the singular Timbrook character, and I hope that will suffice. Timbrook is as deadpan, low-key, and stoic as anyone I've ever met. Add into the equation his being a salty, seasoned veteran; battle-hardened and gritty. If he had a sense of humor (he doesn't) it would be dry and macabre. He is, near as I can get, like an Eeyore with confirmed kills. That said, on with the story.

We were driving along outside Ramadi when we spotted some camels! Such an iconic symbol of the Middle East, and these were the first we'd seen. I was ridiculously excited. They weren't even in a zoo or anything, they were just loping around all unfettered. I felt like I was on safari. When we got back and parked, I went up to Timbrook and effused, "Did you see those camels?" Close-mouthed and with his back to me: "Yes." "Well you could get a little excited about it!" I said. Low, under his breath, with a hint of menace: "I saw them already, in 2003. And again in 2005."

"Well fine, be a battle-hardened veteran," I said, "but I still haven't lost my child-like sense of wonder." He fixed me with a cold stare, and with no inflection: "Neither have I.”

Date: Sat, 8 Sep 2007 15:30:13 -0700

We were on a new route, going between Al Asad and Fallujah, necessitated by the destruction of a bridge several weeks previous. Despite the recent history of violent bridge-bombing, it was not a route upon which there were expected to be any armed obstacles, or really excitement of any sort. The route was rural, and decidedly unfrequented, and the sand blown into the roadway was deep and powdery. My wandering attention was drawn abruptly away from reverie to radio, as an uncharacteristic silence had begun to descend across our airwaves.

It had started with the recon vehicles, a forward element far out in front of the convoy that is usually a reliable source of useless chatter, progressed from there to the convoy commander at the head of the main body, and continued in order down the line. One by one the vehicles from front to rear were going quiet, cause unknown. It couldn't have been anything dangerous; danger is reported quickly and with diligence, corroborated along until everybody is well aware. The quiet was, however, unprecedented, and the order in which it had swallowed the convoy suggested that whatever was being reacted to was quickly approaching my vehicle. That, and there was something decidedly provoking on the wind.

It was oil. A big patch of oil spanning the road, coming up out of the ground of its own accord. There was no visible machinery or harvesting apparatus, no pump or derrick or pipeline. It was wild oil, and it was beautiful. As we crossed its surface, above it on the elevated roadway, it was not black but a dark rich brown, iridescent at the ripples and edges, and redolent, aromatic. It flickered in sunlight like water at sunset, and smelled like potential. It smelled like industry, energy, hegemony and power.

As we crossed it I thought of Pizarro at El Dorado. I thought of Ulysses lashed to a mast. After it was past I realized I had been holding my breath, and so had everyone else in my truck. My driver Mondesir, one of the greatest men I've met, turned to me just as the spell was breaking and said, "That... was amazing."

We had all of us of course, there in the convoy, seen oil before at some point in our lives, but none of us since July in Rashidiya. Oil is made from death, you know: stars make the carbon and scatter it when they die, organisms collect it and, upon expiring, put it into the earth. Do I honestly believe that America is in Iraq just for oil? Emphatically no, I don't think that's the case. Would we, however, be here if the oil wasn't? No, I really don't think we would.

Subject: Warning:

Date: Mon, 17 Sep 2007 15:58:58 -0700

Warning: the following message contains adult language and ribald humor, and may not be suitable for children, curmudgeons, schoolmarms, teetotalers, or Mormon missionaries. Living on a military base here in Ramadi, everybody shares a room with several roommates. All meals are taken in a large and crowded dining facility, and the "buddy system" is mandatory for all other activities. This of course keeps us safe and accounted for, but it brooks no privacy or quiet self-reflection. So where, you may ask, do deployed servicemen ruminate? Where do they ponder, stew, and reflect? Where can we express our unguarded opinions? Where can we indulge the silly or absurd? Well, in the only place where, by necessity, you cannot be followed: the restroom stall.

So it is that our public restrooms become the last surviving forum of free expression. It is only through crapper graffiti, I contend, that one can ascertain the raw, unedited spirit of the resident troops. A commander eager to accurately gauge his subordinates' unvarnished mood need only, I believe, eat more bran. And each area's designated water closets reflect their patron's specific culture. Marine Corps porta-johns, for instance, have graffiti recognizably distinct from their Army counterparts. The Army seems to lean towards the existential, with a lot of "Why are we here?"s and "What good will this do?"s. Also a lot of depressingly mopey amateur poetry and dark emo song lyrics. I think I saw some Emily Dickinson once. The Marines, on the other hand, seem much less preoccupied with the grand or intangible, and more interested with the here and now. And sadly less articulate. "My Staff Sergeant is a dick" is a consistent favorite, with infinite variations, as is "I hate this place." Spelling also continues to perplex and befuddle Marines far more than Army personnel, although in our defense we Marines think proper spelling is pretentious and conceited and unimportant.

As for the Air Force, their scribblings belie their superior technological savvy, with all sorts of blog, e-mail, and MySpace addresses, most of them soliciting gay sex. Yeah. It’s true. There are, of course, toilets that are shared by all, and these become fascinating hosts to ongoing debates. "Marines are stupid" cunningly rebutted by "The Army is chickenshit paper-pushers" answered by a cogent "are chickenshit paper-pushers, stupid." You can also, in these diversified crappers, stumble upon rudimentary anthropological research: I saw underway a voluntary public opinion poll that took the form of two headings, "tits" and "ass," with hatch marks under each recording the subjects' preferred criteria. In case you're wondering, ladies, "ass" was winning by a mile. I actually contributed to this one, adding my own heading entitled "personality" and an accompanying hatch mark that, sadly, remains to this day alone.

Finally, the last writing of note (a pun!) found in the communal crappers comes not from visitors, but from poorly translated signs hung up here and there. I will present some by number:

1. (seen by the trashcan) "Get off your refusals in the wastebasket"... getting your refusals off, especially in a wastebasket, is a felony.

2. (seen by sink) "Use sink after you use it"... this one seems to endorse dangerous and open-ended obsessive-compulsive behavior.

3. (seen on bottle of hand sanitizer) "Do not put in children"... the list of things that should be put in children is very short, and none of them are found in public restrooms.

Subject: Iraq says goodbye

Date: Tue, 16 Oct 2007 08:25:00 -0700

Yesterday was my last day in Iraq. I was excited by the occasion and had trouble sleeping, so I went outside to waste time and wait for sunrise. I was still insomniac when, around 0430, thinking I had mere hours to go, alarms sounded that hadn't been heard on that base for almost a year. It was incoming mortar fire, and as there were no shelters in running distance I could only sigh, look up at the stars, and wait. Nothing landed anywhere near me, in fact I never even heard an explosion. I went inside our tent and finished packing. P.S.: more porta-john graffiti I have to share—"Lance Corporal Hanson was here, the Bush twins weren't"

Subject: summation

Date: Mon, 22 Oct 2007 03:21:13 -0700

While I was still in Iraq I got several e-mails that were, when reduced, really kind of plaintive questions. Why are we there? What are we doing? I was careful not to address these queries while I was there, and it was tough not to, really a kind of verbal tap-dance, for several reasons. One, I was possessed of a deployed serviceman's arrogant disdain for civilians employing the pronoun "we." More sincerely, it was because I understood that the reason I was being asked, and not, say, a local congressman, was because I was the one with the unique view of the business end of our foreign policy. I was sort of hoping the same thing, really, that out there where the meat was hitting hot copper there might be offered some sort of insight into the why of the where, so to speak, the answer to the one big question: Why Iraq, of all the Godforsaken Places?

Still, at the time I didn't feel I had a unique perspective of that at all. I had a journeyman's perspective and a laser narrow mind, all thought and reflection subservient to the ultimate objective: return vehicle 3A to their situations of origin with zero loss of life and all their f-a-c-u-l-t-i-e-s intact. 3A was my crew not my vehicle, for anyone who didn't know, and they are all back healthy now and no longer my concern, thank goodness for that 'cause they are hateful delinquents all.

But then, during my free time in Ramadi all I ever read about was Iraq and Al Qaeda and Bush's foreign policy and his cabinet and their decision making process and the dizzying feud between Rumsfeld and Powell and their respective departments, about the CIA and the Taliban and the Sunni vs. the Shia vs. the Turkomen and the Kurds and the Christians and the (gasp) Jews... by the way it is absolutely unfathomable how deeply these Arabs fear (not hate, mind you, but fear) and mistrust the Jews, as if it were nature and not nurture at all...

And I'm back, and not out there anymore, and honestly I'm happy and slightly drunk and not the least bit guilty that I survived, or at least I’m trying to be, and I figure what the hell? I did actually compile several unique perspectives and insightful experiences, so why not share them with some people and if I come across a little hostile or my insights are tedious… then what the hell?

So here we go, what I learned, first question: What are we doing in Iraq?

Answer: What America is doing now in Iraq, and I mean RIGHT NOW in Iraq, forget about what it WAS doing or what it INTENDED to do at the OUTSET or what professional analysts who are a fortnight behind and not fresh from the fight like yours truly are saying is being done… what America is doing right now in Iraq is nation-building in the purest, noblest, most hubristic and worthy sense of the word. For Iraq has never been a nation before, you see—ask the British who drew their arbitrary borders around a seething hive of warring tribes and tried to hold it themselves for a while.

The British retreat in the 1920s is one of the only things that all the "Iraqis" can still smile about, that and the Iraqi girl doing so well on Lebanon's version of American Idol. Iraq has never been a nation before. But it is miraculously showing signs of it now, and America is insisting (at great and bloody cost to itself) that they be a free and democratic nation, and the excitement there is palpable and crazed and murderous. They are still killing each other at a rate that modern Americans find appalling, but to an American from 1776 I think it would seem nostalgic and progressive. We, America, are nation-building for a reluctant populace and playing gun-toting midwife to a very complicated birth. But it is crowning and the consequences of success are cosmic. I can't believe we ever tried, but if we pull this off, can you imagine? We will have been the only country ever in any people's recorded history to have made another culture free. Do you see how amazing, how wonderful, how insanely beautiful and arrogant that is? It's impossible, it's godlike, it's stupid to ever try. Just like walking on the moon. Which means it is ours, merely to reach for it and it is ours, not Iraq itself but that laurel.

So that's the What in the What are we doing. What's the Why? Why are we doing this in Iraq? That question is the more difficult because it is mixed so inextricably with the When. It might become clearer upon extrapolation, so...

Here we go, what I learned, second question: Why are we in Iraq?

Answer: We are in Iraq because we are building a friendly nation in a hostile and unforgiving region. We are in Iraq because we are bringing the Western gifts of freedom and democracy to a beleaguered and embattled people. We are in Iraq because we are liberating the Iraqi people from a tyrannical and oppressive despot. We are in Iraq because we are severing their state's official support of Al Qaeda. We are in Iraq to find and neutralize a madman's stockpiles of weapons of mass destruction. We are in Iraq to enforce internationally recognized embargoes and the No-Fly-Zones specified therein. We are in Iraq to prevent the regime's barbaric attacks upon their own Kurdish citizens to the north. We are in Iraq because they invaded Kuwait and currently threaten the Kingdom of Saud.

Those are eight reasons I found in my research, all of them answering the question of Why are we in Iraq, all of them having been the officially expressed justification for involvement in Iraq at one point or another. If you care to review or if you are particularly astute, you will notice that I have arranged the reasons in a reverse chronological order, starting from my recent experience and dating back to the first Gulf War, with Bush Senior and Stormin’ Norman and all that visceral yet clinical bomb footage. Now you see why the question inevitably involves a When qualification?

The official Why has changed like a bend in a river, always the same place but the substance is constantly flowing, and I could just congratulate myself all night for an analogy like that. Please note that nowhere mentioned even once in more than a decade in any explanation is the word oil, nor the phrase 9/11. We are always trying to help people to our own detriment here in America, or so our officials would have us believe. Martyrs and altruists are we all, on the books, and it sounds so bloody pathetic when you read it that you wonder why, and when, you as an American became such a pansy that three iconic and secured edifices vital to your beloved homeland could be destroyed by suicidal marauders with naught but box knives and your sworn protectors do nothing but bring peace and freedom and elections and happiness to all involved. Well, they didn't, those sworn protectors, they didn't bring peace and freedom and elections and happiness at all. They brought vengeance and pain and upheaval and blood just like you knew they would the entire time. That's why he was elected again.

So stop asking. This Iraq thing started I was in sixth grade.

The What now has been answered as best I can, the Why and the When have been discoursed upon (the original mystery of Why in the First Place is seriously beyond my ken, no amount of research or experience having shed any light upon that, why America ever took notice of this particular backwater) the Where of course being a given, there is only one thing left...

So here we go, what I learned, third question: How are we in Iraq?

Answer: Oh, this is familiar ground, this is comfortable. Those other answers have been a mixture of experience and data analysis, this one is just pure experience. Nobody has to be mentioned in this category that I haven't met, no policy here has to be discussed that I haven't personally enforced. How are we? How are we implementing this fantastic chimerical agenda? How, nuts and bolts, does intent translate to action? Through me and those like me, that's how.

First swallow this: Pie in the sky (everyone's best intentions) plays a tortuous game of telephone from civilian policy-makers (our elected representatives) through political-military creatures (generals and hopeful colonels of every service) to feisty yes-men (commanders of each artificial partition of Iraq) to battlefield commanders (whose job is to try to impose instructions upon reality) to commanding officers (who have no other job but to pass things on to) platoon commanders (who are frat boys who might or might not have anything to add to the process) to a platoon sergeant whose job I can't even parenthesize because in my experience he was a stunted child, to me (a fire team or vehicle commander), and from me to 3A, the best crew that ever got in so much trouble.

Out of all those folks, the only people involved in the How are the platoon commander on down, and honestly at that point the pie in the sky intent has been so filtered that I felt completely justified interpreting every instruction however I pleased, as did all the vehicle commanders, really, with varying results. Which meant that, on a practical level, locals and Iraqi citizens that came in contact with 3A were treated, usually, with respect and a hopeful apprehension. Damage to any Iraqi building or structure by 3A was avoided or minimized, and 3A tried to present a very professional appearance to Iraqis as a diplomatic measure, and to other service members (Army, Navy) as an example.

Of course at the same time 1A was hitting every traffic cone, concrete barrier, and Iraqi Police truck they could, 3 was yelling filthy things at women and children over their P.A. system, 2A was throwing bottles of urine at street urchins, and the Army shot at every shadow that startled them from slumber. It sounds chaotic, but I'm being droll. The big picture is that the original quagmire has been partly salvaged by cool heads like Gen. Petraeus and Gen. Mattis, who actually were commanders during Operation Enduring Freedom 1, but were relieved because their policies were too forward-thinking and enlightened, but have since been reinstated to higher authority due to the suicidal idiocy of everyone else. Their good ideas have started to filter down through the aforementioned tortuous telephone cycle and things were getting measurably different for those of us on the ground even during my brief tenure. It was getting better, quantifiably, even while I was there.

I'm done, that's it, but I don't think I stressed the last part enough: it was getting better, noticeably better, just while I was there. And I want to stop there. That was all the questions answered in one fell swoop. Figure the rest out yourself.