You can’t avoid George R. R. Martin, the bearded and be-hatted author of A Song of Ice and Fire, the very, very long fantasy series that claimed national attention when HBO adapted it to the small screen as Game of Thrones. The Internet loves Game of Thrones, from its dwarf Lannisters to its age-inappropriate breastfeeding to the HBO-trademarked combination of naked bosoms and fake blood. I kind of enjoyed the first season but lost interest at the second. At some point I bought a set of the first four novels.

I’d always assumed that Martin’s novels were considered entertaining dreck, genre trash worth reading on airplanes, while waiting for a court appearance, or during a 15-year-old’s summer vacation. Last week I began searching for critical reviews of Martin’s work; to my surprise I encountered nothing less than fulsome praise. Two articles from the Guardian come the closest to criticism—one apologetically mentions Martin’s “creaky prose,” the other derides the unattractive cover of the UK edition of the first volume. Both admit, in their headlines, to being “hooked.” Other critics, cited below, are less moderate. Martin, apparently, is a genius, perhaps the greatest living novelist, a man who gets credit for having re-invented the fantasy genre as a grim, largely un-magical world inhabited by morally gray characters.

In the mass media criticism of Martin certain words resound: original, gritty, complex, free of clichés, low-fantasy, political, richly imagined. For the critics Martin rarely writes; he reinvents or transcends. And here I was thinking that A Game of Thrones consisted largely of reheated clichés, that the style was much closer to the lesser works of Stephen King than William Faulkner, and that the narrative bent unnecessarily (and often) to grotesque humiliation, sexual and otherwise, of women. Apparently I was totally wrong.

I also recently read Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, a long series of poems on the theme of King Arthur’s retreat from Camelot into death (Tennyson based the poems on Thomas Malory’s 15th century Morte D’Arthur, which covered much of the same ground). Oddly enough I got the impression that Tennyson’s fantasy epic, published in the mid-1800s, possessed many of the supposedly desirable qualities that critics attribute to Martin’s oeuvre. For instance, rather savage feudal politics, an area of Martin’s reported expertise, suffuse Idylls: Arthur struggles constantly to keep his just, peaceful England under control. There are more correspondences: the poems are not unduly fantastic, they present morally gray characters (and lots of them), they show Camelot and its sylvan, or desolate, or transcendent surroundings with great depth and beauty, they do not lack for horror, or the threat of death, or of worse.

But according to the critics George R. R. Martin has done the same thing, only better, and in over a million words where Tennyson must have used less than a 100,000. I find this confusing—how can Martin get so much credit for originality when it looks, to the untrained eye, like Alfred Lord Tennyson did everything that Martin is supposed to have done, over 100 years ago, in exquisite verse? In this article I propose to resolve this question with an empirical, unbiased comparison of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King and the first volume of George R. R. Martin’s mega-epic. Although we cannot appreciate literature without some level of subjectivity I have attempted to be as rational and as forensic as possible, and I think the reader will find that I have allowed the authors and their works to stand and fall solely on their own merits, at all times reserving and guarding against personal, emotional reactions.

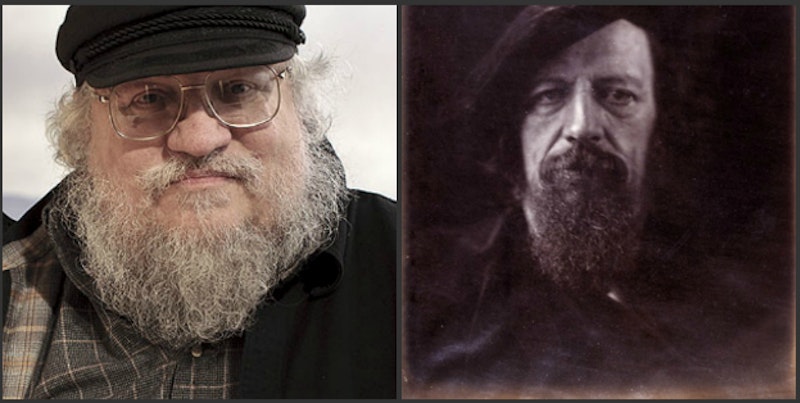

George RR Martin

—Occupation: New York Times bestselling fantasy author, leading figure of American speculative fiction

—Health: Alive, flushed with health, luxuriantly bearded

—Nationality: United States (New Jersey)

—Spouse: “The lovely Parris”

—Works produced as TV show: Yes

—On network television, or cable: Cable

—HBO? Yes!

Alfred Lord Tennyson

—Occupation: Poet

—Health: Dead; when alive, was probably physically weak and clean-shaven (Wikipedia picture shows him with a beard which was almost certainly fake)

—Nationality: European (socialist?)

—Spouse: deceased lady

—Works produced as TV show: No (kind of)

—On network television or cable: sort of, on Starz (Camelot)

—HBO? Definitely not

A Game of Thrones

—Title: Cool and mysterious—what thrones? What kind of game?

—Originality: Takes place in totally new fantasy world called Westeros.

—Fantasy elements: Dragons; exposed breasts; zombies.

—Grittiness: Westeros sets the benchmark for grittiness, ultra-morally ambiguous characters, and original, dark, sophisticated themes in fantasy (example themes: family conflict, political intrigue, dragon husbandry).

—Written in: Gritty sentences.

—Number of characters: Almost countless

—Contains elaborate fantasy genealogy in the back: Yes

—Important moral lessons and character development: Yes, like when the blonde lady discovers how to breastfeed dragons, or when the dwarf learns the true value of friendship from that one prostitute with the funny accent.

—Number of scenes set in brothels/whorehouses/bordellos/etc: considerable.

—Historical relevance: Totally accurate portrayal of feudal system.

—Pages: 807, not counting the appendix!

—Availability: Handsomely packaged with its sequels at Costco, also all other stores.

Idylls of the King

—Title: Misspelled, boring—which king are we talking about here?

—Originality: Stale retread of played-out King Arthur myth; takes place in England.

—Fantasy elements: Most fantastical element is some woman who lives in a lake (easy to do with simple SCUBA/snorkel equipment). One wizard.

—Grittiness: Not gritty at all; less than a dozen decapitations, no directly described rapes. —Some characters (Lancelot, Guinevere, Arthur) mildly ambiguous.

—Written in: European-style “stanzas”; many misspellings.

—Number of characters: Only Arthur, Lancelot, Guinevere, Kay, Torre, and a few of the others knights, and Enid and Geraint, and Merlin, and Vivien stand out; few notable dwarves.

—Contains elaborate fantasy genealogy in the back: no, contains critical notes.

—Important moral lessons and character development: only if you consider characters having feelings, talking about them, and then acting on them to be character development.

—Number of scenes set in brothels/whorehouses/bordellos/etc.: literally none (one rowdy bar scene).

—Historical relevance: Limited; on the one hand, it comes from history times, but on the other, it is very inaccurate and mostly about non-gritty knights who live in fancy tents and own color-coordinated sets of armor. I guess some of it is about the feudal system but none of the political intrigue takes place in exciting locations (whorehouses, bordellos, brothels, etc.) so it is hard to follow or pay attention.

—Pages: 371 (total!)

—Availability: the kind of bookstore that has a poetry section.

Key passages compared:

Introductions:

GRRM:

He found what was left of the sword a few feet away, the end splintered and twisted like a tree struck by lightning. Will knelt, looked around warily, and snatched it up. The broken sword would be his proof. Gared would know what to make of it, and if not him, then surely that old bear Mormont or Maester Aemon. Would Gared still be waiting with the horses? He had to hurry.

Will rose. Ser Waymar Royce stood over him.

His fine clothes were a tatter, his face a ruin. A shard from his sword transfixed the blind white pupil of his left eye.

The right eye was open. The pupil burned. It saw.

ALT:

And so there grew great tracts of wilderness,

Wherein the beast was ever more and more,

But man was less and less, till Arthur came.

For first Aurelius lived and fought and died,

And after him King Uther fought and died,

But either failed to make the kingdom one.

And after these King Arthur for a space,

And through the puissance of his Table Round,

Drew all their petty princedoms under him,

Their king and head, and made a realm, and reigned.

And thus the land of Cameliard was waste,

Thick with wet woods, and many a beast therein,

And none or few to scare or chase the beast;

So that wild dog, and wolf and boar and bear

Came night and day, and rooted in the fields,

And wallowed in the gardens of the King.

And ever and anon the wolf would steal

The children and devour, but now and then,

Her own brood lost or dead, lent her fierce teat

To human sucklings; and the children, housed

In her foul den, there at their meat would growl,

And mock their foster mother on four feet,

Till, straightened, they grew up to wolf-like men,

Worse than the wolves.

Critical commentary:

We see here Martin’s economy and grace, the supple language that he employs invisibly to drive his intricate, gritty plot (based, according to legend, on the War of the Roses, which is extremely historical, complex and gritty). Even this short section from the opening of the book demonstrates the mystery and detail of Martin’s fictional world—a world in which people are called “ser” instead of sir and “maester" instead of master, a world in which the dead can rise in paragraphs of less than ten words, a world in which eyes can scarily and suddenly see. Shades of other greats: Faulkner, Steinbeck, Crichton.

Tennyson does not fare so well—Cameliard has some historical resonance (it appears in Malory), but it lacks the punch of what New York Times critic Dana Jennings calls Martin’s “world-drunk naming of places”—wild regions like “Sea Dragon Point” and “Rook’s Rest.” Who can imagine Cameliard (other than, perhaps, a man looking at a picture of a camel and a leopard)? And who could fail to imagine the vividly-named Rook’s Rest, a place where rooks might rest after flying from some other place (perhaps Sea Dragon Point)?

We encounter more problems with Tennyson’s wolf metaphor, which might sway us momentarily with its prettiness, its careful phrasing, its shades of human and animal menace, mother’s mourning (of various species), blood, closed spaces, stench, the sound of growls. Yet could we imagine a shrewd writer like Martin falling for this kind of implausible interspecies suckling? (Okay, Martin does end A Game of Thrones with Daenerys breast-feeding a brace of dragons, but he spends 800 pages building up to it, and introduces it with a terrifying, fiery ordeal, he doesn’t just drop it in our laps in the first chapter). I hesitate to mention the effect that Tennyson’s writing might have on children, who would surely be encouraged to seek out and nurse from wolves or wild dogs; clearly Tennyson lived in a less litigious time.

Conversations:

GRRM

[Daenerys and Viserys, noble siblings involved in political intrigue, are arguing]

His fingers dug into her arm painfully and for an instant Dany felt like a child again, quailing in the face of his rage. She reached out with her other hand and grabbed the first thing that she touched, the belt she’d hoped to give him, a heavy chain of ornate bronze medallions. She swung it with all her strength.

It caught him full in the face. Viserys let go of her. Blood ran down his cheek where the edge of one of the medallions had sliced it open. “You are the one who forgets himself,” Dany said to him. “Didn’t you learn anything that day in the grass? Leave me now before I summon my khas to drag you out. And pray that Khal Drogo does not hear of this, or he will cut open your belly and feed you your own entrails.”

Viserys scrambled back to his feet. “When I come into my kingdom you will rue this day, slut.”

ALT

[Lancelot and Guinevere argue; Guinevere has heard rumors that Lancelot has taken another lover. Lancelot assures her that they are false; he presents her with jewels, and with an enormous diamond won at one of Arthur’s tournaments.]

‘An end to this! A strange one! yet I take it with Amen.

So pray you, add my diamonds to her pearls;

Deck her with these; tell her, she shines me down:

An armlet for an arm to which the Queen’s

Is haggard, or a necklace for a neck

O as much fairer—as a faith once fair

Was richer than these diamonds—hers not mine—

Nay, by the mother of our Lord himself,

Or hers or mine, mine now to work my will—

She shall not have them.’

Saying which she seized,

And, through the casement standing wide for heat,

Flung them, and down they flashed, and smote the stream.

Then from the smitten surface flashed, as it were,

Diamonds to meet them, and they past away.

Then while Sir Lancelot leant, in half disdain

At love, life, all things, on the window ledge,

Close underneath his eyes, and right across

Where these had fallen, slowly past the barge.

Whereon the lily maid of Astolat

Lay smiling, like a star in blackest night.

Critical commentary:

Martin’s political intrigue and wordplay is as swift and electric as his action—the characters’ rich histories infuse each scene with complex and gritty layers of meaning. Like, what happened that day in the grass? I don’t remember, but I know it must have been spectacular. Dany and Viserys are the kind of indelible characters that become touchstones for our culture, like Rachel and Ross, or Ron Weasley. As Time book critic Lev Grossman (who called GRRM “The American Tolkien”) writes, “Martin is… a deft and inexhaustible sketcher of personalities.” That’s putting it mildly, like saying that Shakespeare turned out the occasional good play and sonnet (though Martin, unlike Shakespeare, has no room for dud characters in his expansive cast).

I won’t even mention the psychological and anthropological acuity of Dany’s gradual conversion to the richly-drawn and breathtakingly original Dothraki steppe culture, a transition that recalls Last of the Mohicans, Heart of Darkness, The Poisonwood Bible, the Golden Bough and Malinowski, the Kids in the Hall sketch in which the cast converts en masse to the wild ways of an expansive garden center. In an exquisite later scene Daenerys has to eat a stallion heart (“The wild stallion’s heart was all muscle,” GRRM writes) as part of a ceremony; she gnaws it, sans cutlery – how’s that for gritty?

Tennyson, on the other hand, plays things much too subtle. Sure, we might admire the way in which he evokes the play of passion, antipathy, boredom, and guilt in Lancelot and Guinevere’s relationship, the naturalistic turn from argument to action, described in an image that we cannot but admit is pretty: the flashing diamonds plunging into the river. We might even admit that Tennyson has found an engaging way to move the narrative along to the arrival of Elaine’s corpse, which Lancelot sees as he leans out the window, disgusted with Guinevere and with himself. Elaine, by the way, does not even rise from the dead to attack anyone—she rests on a bier and eventually gets buried.

Little Elaine has driven herself to death for love of Lancelot, a passive career unfortunately typical of Tennyson’s female characters (other than Guinevere, Vivien, Enid, and the menacing, grim Lady of the Lake)—no brawlers they, no horse-queens or sharp-tongued Martin-esque whores.

One might almost be fooled into thinking that Tennyson shows graceful, quiet insight into his women, who inhabit a courtly but ultimately real world in which they cannot separate their fortunes from the pride and the desires of men. But in the end Guinevere discards the diamonds (another passage to be kept from impressionable children), and the scene ends without a clear resolution of her relationship with Lancelot. In Martin we would be sure that this was some kind of productive, gritty ambiguity—but can we extend the same credit to Tennyson?

Dining:

GRRM

On a hill overlooking the kingroad, a long trestle table of rough-hewn pine had been erected beneath an elm tree and covered with a golden cloth. There, beside his pavilion, Lord Tywin took his evening meal with his chief knights and lord bannermen, his great crimson-and-gold standard waving overhead from a lofty pike.

Tyrion arrived late, saddlesore, and sour, all too vividly aware of how amusing he must look as he waddled up the slope to his father. The day’s march had been long and tiring. He thought he might get quite drunk tonight. It was twilight, and the air was alive with drifting fireflies.

The cooks were serving the meat course: five suckling pigs, skin seared and crackling, a different fruit in every mouth. The smell made his mouth water. “My pardons,” he began, taking his place on the bench beside his uncle.

“Perhaps I’d best charge you with burying our dead, Tyrion,” Lord Tywin said. “If you are as late to battle as you are to table, the fighting will all be done by the time you arrive.”

“Oh, surely you can save me a peasant or two, Father,” Tyrion replied. “Not too many, I wouldn’t want to be greedy.”

ALT

[Earl Doorm has captured Enid and her husband Geraint, who got knocked out fighting some knights. The earl and his men ignore Enid, who attempts to staunch Geraint’s wounds, and weeps.]

Earl Doorm

Struck with a knife’s haft hard against the board,

And called for flesh and wine to feed his spears.

And men brought in whole hogs and quarter beeves,

And all the hall was dim with steam of flesh:

And none spake word, but all sat down at once,

And ate with tumult in the naked hall,

Feeding like horses when you hear them feed;

Till Enid shrank far back into herself,

To shun the wild ways of the lawless tribe.

But when Earl Doorm had eaten all he would,

He rolled his eyes about the hall, and found

A damsel drooping in a corner of it.

Then he remembered her, and how she wept;

And out of her there came a power upon him;

And rising on the sudden he said, ‘Eat!

I never yet beheld a thing so pale.

God’s curse, it makes me mad to see you weep.

Eat! Look yourself. Good luck had your good man,

For were I dead who is it would weep for me?

Sweet lady, never since I first drew breath

Have I beheld a lily like yourself.

And so there lived some colour in your cheek,

There is not one among my gentlewomen

Were fit to wear your slipper for a glove.

But listen to me, and by me be ruled,

And I will do the thing I have not done,

For ye shall share my earldom with me, girl,

And we will live like two birds in one nest,

And I will fetch you forage from all fields,

For I compel all creatures to my will.’

He spoke: the brawny spearman let his cheek

Bulge with the unswallowed piece, and turning stared;

While some, whose souls the old serpent long had drawn

Down, as the worm draws in the withered leaf

And makes it earth, hissed each at other’s ear

What shall not be recorded

Critical commentary:

Here we see Martin’s sure, sharp wit, what Dana Jennings eulogizes as the “blunt and bawdy earthiness that befits the son of a Bayonne, N.J., longshoreman.” Save me a peasant? Now THAT is fantasy hilarity that the whole family can enjoy. Jack Vance, eat your heart out (or maybe try eating a stallion heart!).

Tennyson sets a mean table—where Martin gives us crisp-skinned pigs garnished with five different fruits. (What might they be? We can only wonder.) Tennyson dwells on one bitter Anglo-Saxon word, flesh—none too appetizing. We might grudgingly admit that Tennyson’s dining scene contains some effective action—the percussion of the knife against the table, the gross chewing, Enid cowering, the spearmen and their trulls hissing through mouthfuls of seared meat. And we might admit that Doorm’s speech has its moments of grace and power—it does, after all, combine a proposal of marriage, a boast, and a universal threat (“I compel all creatures to my will”); it lacks, for certain, a tangy Bayonne-bred wit.

These short excerpts, of course, cannot demonstrate the mastery of plot that Martin shows with every twist. And of course I have limited my comparison to the first book of his Song of Ice and Fire series, a gesamtkunstwerk that can only be truly appreciated in its colossal entirety. “The narrative intricacies mount and mount.” writes editor Verlyn Klinkenborg in The New York Times, “’Plots within plots,’ one of the characters thinks, ‘but all roads lead down the dragon’s gullet.’”

Martin’s scale may be epic, but he never forgets the personalities that drive his tale— “Like Wagner, he gives each of his characters leitmotifs that recur and recur in their streams of thought,” Lev Grossman writes (the dwarf Tyrion’s thought-motif is “wherever whores go”). Grossman goes on to compare Martin to Anthony Powell (Powell “can't twist a plot like Martin”), adding modestly that “[Martin’s] skill as a crafter of narrative exceeds that of almost any literary novelist writing today.”

Powell, I suppose, may have included some ideas on the consequences and ambiguities of war in his A Dance to the Music of Time. He may also, on occasion, have demonstrated modest gifts for sociological and psychological insight, and for describing the troubled relationships of fathers and sons, and mothers and daughters. But nothing, I gather, on the level of Martin, who has exceeded Powell in ambiguity just as surely as he has in plot.

Ambiguity, we must always remember, is the hallmark of grittiness and realism in fantasy literature. Books in which good and evil clearly oppose one another are tired and facile; modern readers crave stories in which every character is torn by demons internal and external, faced with moral compromise and bad choices at every turn, condemned to destroy the things he loves best, tossed on the horns of a dilemma, between a rock and a hard place, etc. Characters who are not thoroughly, consistently, and proactively ambiguous bore us.

Grossman skillfully sums up Martin’s magisterial contribution to this emerging literature of realistic gray-area grit: “It's as if he's trying to show us that every fight is both triumph and tragedy, depending on where you see it from, and everybody is both hero and villain at the same time. Or maybe not even that. ‘There are no heroes, only whores,’ says Theon.”

It is such breathtakingly fresh ideas, such entirely novel approaches, free of all the weary clichés of the old, that create new literary modes and new ways of thinking. Life in the age of Martin is what it must have been like to live during the first performance of Tannhäuser, the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses, the release of the early novels of Pynchon and Vonnegut, the first tentative brushstrokes of Thomas Kinkade. Martin has opened a door for us, and we owe it to the career of human letters to walk through it.