Jules Feiffer broke into comics in 1946 at age 17, working with Will Eisner on, among other strips, Eisner’s acclaimed series The Spirit. The Spirit’s nominally a super-hero, but has no superhuman powers—he’s more like a private eye in a domino mask, moving through an impeccably-designed noir world. Now, at 89, Feiffer’s finished a trilogy of 150-page noir-crime graphic novels. The graphic novel is a form of comics that didn’t exist in the American commercial publishing world in the post-war years, but Feiffer’s created a set of masterpieces that together have to be considered a work of genius.

Kill My Mother, published in 2014, begins in 1933 in the metropolis of Bay City and ends 10 years later. 2016's Cousin Joseph is a prequel that takes place just before Kill My Mother begins, showing us background and revealing unpleasant truths. This year’s Ghost Script moves forward to 1953, paying off 20 years of character arcs.

Kill My Mother opens with two teens, a girl and a boy. The girl, Annie Hannigan, is the daughter of Elsie, who turns out to be the secretary of Neil Hammond, a private eye. Hammond used to be a cop, but his partner, Elsie’s husband and Annie’s father, was shot dead. Hammond doesn’t seem to be too interested in trying to find out who did it, though, especially when a tall blonde walks through his door and hires him to find a woman who looks suspiciously like her.

The book’s the story of the women, for the most part: Annie’s resentment of Elsie, Elsie trying to help Sam, the mysterious women Hammond’s investigating—and then there’s a masterfully-timed jump forward, and the story takes a turn into Hollywood, and radio, and a USO tour to the South Pacific. And it all fits perfectly, the web of violence and secrets stretching but not breaking.

Cousin Joseph fills us in on the last days of Sam Hannigan, who wasn’t entirely the character that the other characters remember. He’s involved in strike-breaking, and working with the reclusive “Cousin Joseph” to muscle movie producers into making anti-communist and right-wing films. The Ghost Ship continues the themes of cinema and politics, as the survivors of the first two books get involved with a mysterious movie script that may or may not exist, exposing the secrets of the blacklist.

The story unfolds through gunshots, riots, beatings, betrayals, ambition, and often-misplaced idealism. These books are thoroughly noir, not necessarily visually dark, but downbeat and frequently tragic. The stories of the various characters intersect, gaining devastating power from foreshadowing and from the secrets they hide from each other and how those secrets come to light or do not.

Crucially, the overall story structure works. Feiffer recalls, in a postscript to the second book, wanting to be an adventure-strip cartoonist when he was a boy; he pulls it off here. The conventions of noir and of hard-boiled crime stories (not the same thing, though often co-existing) are used to create a melodrama of coincidences, and those coincidences bring out character and tragedy and compromises. A good genre tale of any kind shows how the conventions of its genre heightens drama and brings out emotional depth; so it is here.

As with the genre, so with the artform. This a bravura display of comics craft, paradoxically so effective it can go unnoticed. Angles are well-chosen, the camerwork fluid. Characters are given flowing, realistic body language. Fight scenes are kinetic and physical. Page design is varied: classical panels with borders and gutters, un-bordered images in sequence, whole pages designed as one overall setting with multiple images in sequence within it (cars, for example, moving through a landscape), sometimes simply full splash pages or sequences of splashes.

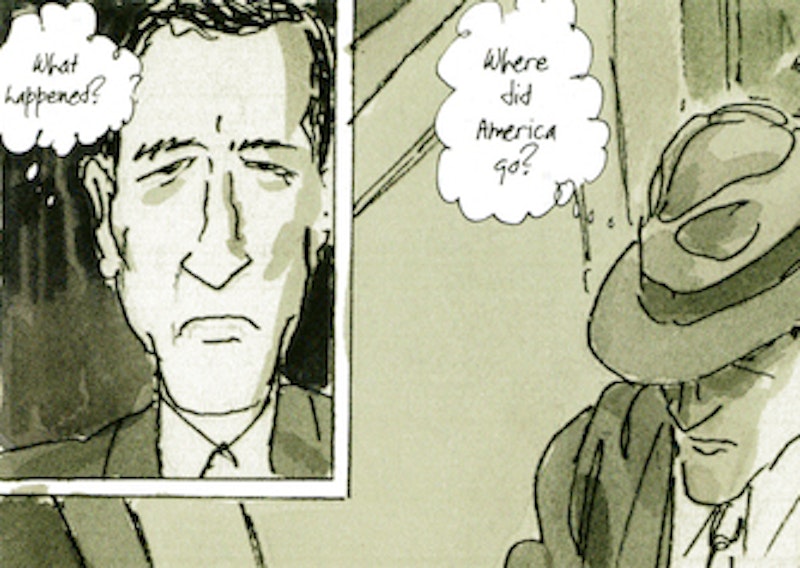

Those last gain extra force from the sheer size of the books, reminiscent of a European album. It emphasizes the physicality of the art. Feiffer’s not known for his precise draftsmanship, but his style here strikes me as both more illustrative than his best-known work and more fluid. Backgrounds, props, and costumes are well-designed but rendered in loose scribbles. Perspective’s always precise, but the lines of the bodies look like gesture drawings as they dance or argue or beat the crap out of each other. Color’s muted, coming mostly in the form of watercolor washes in shades of gray and brown, only a few highlights giving startling relief. It’s a noir palette, and the hand-colored look can’t help but echo the old-fashioned feel of the story.

That’s also brought out by Feiffer’s vision of the American urban fabric of 1933, ‘43, and ‘53. The visuals are accurate to the period but so’s the dialogue. So are the situations. These aren’t Hollywood stories but they’re set in and around the dark side of Hollywood, and you can hear the rhythms and echoes of film dialogue in the tightness of Feiffer’s script.

But these books are not film, they’re comics, and offer a master class in comics technique. At a number of moments you can’t help but think of Eisner—indeed, the Spirit’s mentioned late in the third book. Aside from tone, there’s an Eisnerian sense of how to visually depict character. There’s a page that’s a series of studies of a man’s head from behind, with dialogue spoken to him and by him, and it builds to a single quarter-face image; it’s dramatic, it builds a sense of who the man is from the set of his shoulders, and without recalling anything specific I can think of it reminds me intensely of Eisner’s work.

Eisner was not this subtle about character, though, and not this politically aware, either. Feiffer displays a keen awareness of both what’s now called identity politics and traditional power politics. He notes in his Foreword to The Ghost Script that he didn’t intend to write a political work when he did the first book; but seeds there blossom in the third to a story about leftists versus liberals versus right-wingers of all kinds. Nobody’s pure here, though. People can hold views we think of as repugnant but also have a code of honor; other people can be trying to make the world better and yet still have tremendous flaws.

One must be careful in saying this. Feiffer’s not throwing in flaws or virtues to humanize saints or devils. “Our aim is not to write an open-handed script that finds fault with both sides: the persecuted and the persecutors,” one of his characters says pointedly. This is a work, or set of works, that has a convincingly dark view of human nature. There aren’t heroes.

Still, Feiffer’s aware of the way his characters are necessarily part of a culture, of a time, a place and a social status, and how that affects who they are. Feiffer himself was always a sharp critic of 20th-century American masculinity while being himself embedded within it. Here you can see him working with that, recreating the manhood of the 1930, 40s, and 50s. He’s aware of the homosexual undertones male friendship could have, aware of the unquestioning misogyny of the era. But he also takes care to make the books a story of women negotiating their times and coming out in many ways triumphant if not unscarred. Race and ethnicity become more significant as the story goes on, Jewishness and blackness playing into the third book most notably.

The point is these themes are seamless parts of the whole. The books are intricate meditations on the times, then and now, and the tradition of noir. There’s a meta-fictional conceit to the third book that’s perfect: a script that didn’t even exist until rumors about its existence led a group of radicals to write it—the story of the thing preceding the actual story, the script as Macguffin. By that point we’re seeing the book examine its own priors. Characters doubt their ability as private eyes, and look back with nostalgia on earlier characters we know were more flawed.

These are books in which characters are all haunted by the past and ideas of the past. False nostalgia for times that never were is the ultimate cause of great wrongs. The trilogy isn’t really a satire, though. It’s too humanistic for that. If it’s also a genre piece, Feiffer shows there’s no conflict between those things, or between genre and a work of great artfulness. For anybody else this would be a career-defining work; if it isn’t in his case, that’s just because of the range of his accomplishments. By any measure, though, the Kill My Mother trilogy is a massive success.