Princeton, NJ has a few bookstores, less than you’d expect for a university town. Route 1, an unlovely business artery, boasts a Barnes and Noble and a Borders. The town’s main street features a branch of Labyrinth (formerly the much idolized but fundamentally mediocre Micawber Books), which is very nice although it tends to be pricey. Princeton Shopping center, a few minutes’ drive from campus, conceals the town’s most interesting and least necessary bookstore, Chicklet Books. In Chicklet last spring I found the second volume of Jeffrey Ford’s Well-Built City trilogy, a series of short, very strange books that I immediately loved.

I found the books inseparable from the shopping center. Princeton Shopping Center appears to have been planned by an architect of severely limited attention span, abilities, or both. The place looks inside out. In the middle of a vast parking lot it squats, and its ugly storefronts generally resemble delivery entrances. The buildings form a ring, and the interior courtyard is quite lovely—spacious, quiet and green. Last spring whatever cabal owns the center inaugurated a huge renovation, a project that must have cost millions and has made only the most modest improvement on the essential ugliness of the mall.

I have always loved shopping centers that are in the advanced stages of a slide towards abandonment, and that cold spring delivered me a true masterpiece of this sad and dusty genre. The crown for the withered and much-abused head of the shopping center surely was Chicklet, a recent, probably unsuccessful rebranding of an even less popular bookstore whose name I never learned. Chicklet’s owners had purchased the previous store, which was known more for housing a post office branch than for its literary merits, and with this purchase came an entire basement of unsold books. For reasons that I do not understand the new owners chose to clear these books out at $5 per garbage bag. As soon as I discovered this I returned every day for an hour or so of browsing.

And here I found Memorandum, the second volume of Ford’s trilogy; all three volumes turned out to have a certain affinity with poorly planned architecture and feelings of abandonment. The store, unsurprisingly, lacked the first and third books in the series so I began with the second. In another coincidence this is not really a bad way to read the series.

But I should begin at the beginning. The first volume, The Physiognomy, sets the stage with the protagonist Cley, a physiognomist in the employ of Drachton Below, the architect and tyrant of the Well-Built City. If we must fuss with genres the novel falls squarely between fantasy and science fiction, as does Below, Cley’s teacher and antagonist. Below, we learn, has mastered both science and magic, and his city teems with his creations. The atmosphere is of a horrible industrial revolution-era dystopia, more Orwell than Tolkien, and I don’t believe there’s a single fantasy cliché to be found in the book.

The citizens of the Well-Built City receive rank and privilege commensurate with their physical perfection, and the physiognomists determine (with mathematical precision) exactly how close to perfect they are. Our hero, Cley, is a Physiognomist First Class and the beneficiary of a “Star Five” physiognomy, considered just a shade less than Below’s own perfection. So physiognomists are important people, and Cley is an important physiognomist, and he has allowed this power to go straight to his exquisitely symmetrical head. For most of the first novel Cley is cruel and vindictive and petty, like a less physically powerful Patrick Bateman (and without Bateman’s peculiar attitudes towards women). He is also rather funny, and is so totally unaware of how others perceive him that the reader (at least in my case) feels almost charitable about his beastly behavior.

The narrative begins with Cley en route to Anamasobia, a provincial mining town. He suspects that he has been banished there for some real or imagined slight again Below (usually referred to as “the Master”). He cannot say for certain, partly because of the paranoia-inducing influence of Sheer Beauty, a drug of the Master’s own invention to which he is fiercely addicted. A coachman takes him to Anamasobia: “The driver held open the door for me. He was a porcine fellow with rotten teeth and I could tell from one look at his thick brow, his deep-set eyes, that he had propensities for day-dreaming and masturbation.”

Ford uses the full force of his writer’s gifts to develop Cley and Below. Both are insecure, cerebral elitists. Cley’s experiences in Anamasobia mark him terribly and he changes, painfully, through the three books of the series. Below, whose fuliginous humor makes Cley seem good-natured and mild, does not change in the slightest. He remains true to his megalomaniacal vision of a completely controlled society until the bitter end, but Ford draws him with wry humor (if not sympathy) and despite his near-comical evil and depravity he never sinks to the level of caricature. Other characters come and go; some are irritating, others amusing, but none of them as finely grained as the two men whose conflict structures the first two books.

Below has sent Cley to Anamasobia to solve a mystery—the theft of a white fruit that the villagers believe grants immortality. Cley meets a beautiful young woman named Arla Beaton, punches the mayor in the face, and endures an excruciating dinner party. He resolves to examine the entire population for physiognomic flaws and assembles them all at the town’s chapel (a grotesque reproduction of a coal mine). Despite Cley’s hubristic confidence things go south suddenly and thoroughly and his adventure in the territory ends with the town burned to cinders, beautiful Arla mutilated to the point that her face induces fatal apoplexy, and Cley himself shipped to a hellish sulphur mine: Here Cley parts ways with Below’s philosophy. He spends the rest of the series cleaning up the mess this causes, wrestling with what his service to Below means and what he can do to right his terrible wrongs.

I found all three books so imaginative and unique that I hesitate to provide much more detail. I should say that Ford has a gift for creating startling scenes. The second book, Memorandum, takes place mostly in Below’s mind, which gives Ford all the excuse he needs for painting eerie, implausible landscapes that have their own cracked logic and consistency. The final book, The Beyond, sees Cley heading north into the wilderness, another realm of starkly weird panoramas and equally convoluted logics. By the end of the series Cley has made peace with himself and some kind of restitution to Arla, but really most of the narrative exists to serve Ford’s bravura command of the bizarre and the original. Cley’s world resembles no other sci-fi or fantasy that I can think of; its murky morals and outré scenery belong uniquely to Ford.

Jeffrey Ford's Alternate Worlds

The Well-Built City trilogy is the perfect series for those of us who like our weird fiction really, really weird

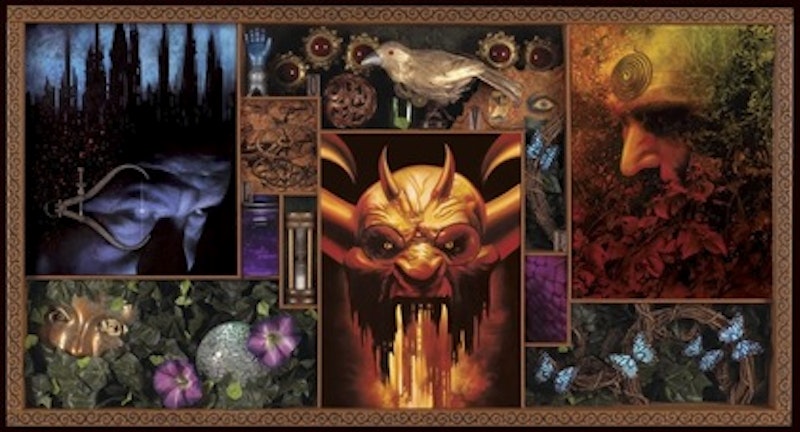

The full triptych of Well-Built City covers, by artist John Picacio.