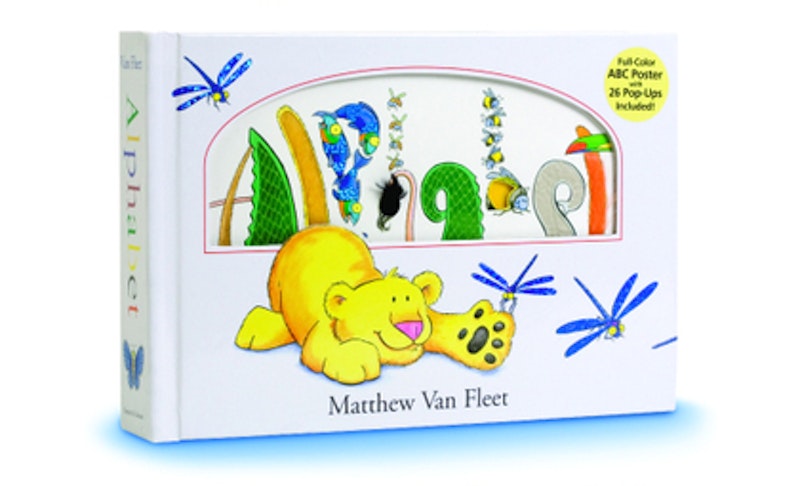

You probably haven’t heard of Matthew Van Fleet if you don’t have a young child, but he’s an institution for my fellow parents. His second pop-up book, Fuzzy Yellow Ducklings, sold a million copies upon its publication in the mid-90s, and he’s since gradually increased the complexity of his artfully designed novelty books. His most recent illustrated pop-ups, Tails and Alphabet, are as mechanically complex as they are educational for toddlers; each relies on a mixture of flaps, textures, movable parts, and Van Fleet’s own expressive drawing style to teach young children simple concepts in a way that doesn’t bore parents.

Van Fleet’s other works include Monday the Bullfrog, a combination book and hand puppet that teaches the days of the week; and a collaboration with photographer Brian Stanton called Dog. The two will follow that up with another book in Spring 2009, "the sequel that no one saw coming," Cat. Van Fleet’s books truly need to be seen and played with to be appreciated. Or, perhaps more accurately, you need to see the reaction of a one-year-old as they begin to understand the correlation between the word “sticky” and the rubberized frog tongue texture at their fingertips. These books may be written for toddlers, but the obvious thought and feeling behind each one convinced me that an adult audience could benefit from a view into Van Fleet’s methods and work. He spoke over the phone from his studio in upstate New York.

SPLICE TODAY: How did you start making children's books, specifically the very ornate, novelty-style books that you're known for?

MATTHEW VAN FLEET: I got into children's books in a really roundabout way. I actually got a degree in biology and never really studied art, but during my [undergraduate] time at Syracuse University, I had a comic strip in the school paper and always loved cartooning. So when I graduated I came to New York to take classes. And I had some stuff published in the Saturday Evening Post and things like that. At the same time I was taking art production classes at night and working as a biochem tech by day. It was a really awful job, working at the Cornell Medical lab. And it just turned out that the first art job I was able to get was as a secretary at Grosset & Dunlap, whose big book was The Little Engine that Could. So I got a job as the secretary in the art department there.

ST: So is there any correlation between your science background and the focus on animals in the books?

MVF: Definitely. I have a real academic interest in animals, so when I work on my books I always go through these huge animal books and get intrigued by the bugs or whatever. Which is why you tend to get weirder animals in my books. When you work in the field as a designer for these mass-market houses—and also as a consumer—you get really sick of ducks and cows and bunnies. So I wanted to get something in there that's a little different.

And I got into doing the textured books from working in a novelty publishing environment. That's how I knew the technical part of making them. Because a lot of people who do children's illustrating and writing tend to come at it from an editorial perspective; I was really coming from an art production standpoint so I knew how to do all the mechanical drawings and the production aspect anyway. If you don't know how to do that—if you're a regular illustrator or writer—it's a lot harder because you don't know the technical parameters. It's not as stupidly easy as putting a flap on a book, for instance. You have to know where the glue's going to go, you have to know the sheet size. So when I started I was already able to make this big comps for the ideas. There aren't a lot of people at the publishing houses that know how to do that; you can't just walk in and say "I've got an idea for a book." You have to have the whole idea, and the pricing in mind.

ST: What's the process then? Do you come up with the subject first, like the alphabet or colors? Or do you start by wanting to incorporate a certain texture or what?

MVF: It's kind of tough. I don't do what mostly people would think, which is to come up with a format first and try to write a book around it. You'll see that a lot, where a publishing house has a format with a window or something, and they'll try to make a book out of it. [Laughs] I remember getting blank dummies from publishers asking me to fill it in. And that's how you get all those really crappy kids books that sit around Barnes & Noble, on the tables, you know?

The way I usually work, though—I'm working on a book right now that's really at the concept stage. I do two kinds of things: one is the photography-based books like Dog, and the others are my illustrated books. But I try and think of a theme first and come up with a list of things that would fit in to that concept. The alphabet book took forever; I had about four different ideas for alphabet books that I comped up over 17 years, and none of them worked. And it wasn't until I did that simple rhyming stuff and trying to get a lot on the page that it started to work.

For the photography books, I really try and write it first. We're doing one for farm animals next, so I try and think of every animal for that environment. And once you get into it, you start researching and find out that there are ungodly numbers of breeds of these things. There's something like 400 breeds of sheep, just in the US. [Laughs] So part of it is that I know so little about these ideas when I start out, and then you get going and figure out which things may or may not work as textures or mechanics. Like a merino sheep, for instance, has real funky hair, and you start thinking, "Oh that might be a cool texture."

ST: But where did that interest in kids' books come from? You have a distinct illustration style that doesn't immediately cry out for children's books. It's more of a political-cartoon kind of thing, with exaggerated facial expressions and lines.

MVF: I was doing a lot of magazine cartoon stuff, and really wanted to be doing a syndicated strip. I'd submitted one way back, right before my first book came out, and the style's the same; my kids books are just like my cartoons, they're just animals. And my whole career, every art director would say, "Oh, it's too cartoony." Which is what everyone said about Dr. Seuss; that's the catchphrase for these dopey art directors who want to think they're doing fine art. [Laughs] And then of course when Sandra Boynton hit it big, I looked at them and said, "What about this, what about Peanuts?" But they're blinded, they think they're doing these fine art books. And I love looking at that stuff myself, it's beautiful. But for my audience, it doesn't sell. I mean, the fine art stuff is lost on a little kid.

ST: What about that audience, though? You make these really ornate books with lots of things to pull and possibly rip, and they're for an audience that, speaking from experience, is prone to destroy almost anything they can get their hands on.

MVF: It's a tough thing, because by the time they're old enough to appreciate it and not damage it, or appreciate the fine art, they're too old for kid’s books. I was a huge fan of those books back in the day that a lot more text in them—like Alice in Wonderland or the N.C. Wyeth books. They're these really fabulously illustrated things, but they weren't picture books. And when I was starting off, there was this disconnect where the books were those kind of elaborately illustrated things but they had two sentences on a page. But for a preschool book it doesn't make any sense to over-illustrate them; you want it to be a more immediate thing, they have to get it. There has to be a recognizable expression from the animals.

Above: a spread from Dog.

ST: You've mentioned names already, like Boynton or Dr. Seuss, but who are your major influences in the kid’s book genre or outside of it?

MVF: The biggest influences on me were Peanuts and Jim Unger, who does "Herman." That's the art style was I really trying to get. But for kids books, I never really looked at a lot of them. I looked at cartooning. As for the writing, I was also inspired by little gag cartoons. All my books, all the jokes are set up like these little visual gags. They don't really have a story line to them, it's just mud being splashed on a vulture or somebody's tail being bitten. Even the photo books work like that, they're just setups for visual gags like a cat knocking over a vase.

ST: But what about that cartooning style seemed suitable for children's books? When did you get that idea if you didn't read that many of them?

MVF: I was doing all these magazine cartoons as I was working as a designer. I was doing all these novelty book mechanical things, and when you're a cartoonist you try everything you can. Magazine cartoons, illustrations, advertising, anything. So I came up with the idea of doing One Yellow Lion. And at the time I couldn't really draw well at all, especially animals. So the comp for that one was this little three-inch square made out of rubber cement and marker drawings. It was more the idea of the novelty—this way of cutting numbers in half. Which is what the publishers are buying, they're looking for a novelty hook to sell. But basically I was already doing that kind of work all the time; I just decided to put my own idea in there.

ST: Did having kids of your own change your approach to the books at all?

MVF: Everybody asks that, but it really hasn't changed anything. It wasn't until my third or fourth book came out that they were even able to use it or appreciate them. Maybe when they're old enough and out of the house I'll look back and think of ways to incorporate kids into the books. But for now they usually just look at the books and then it's "Yeah, whatever" and they're off to do something else. [Laughs.]

ST: Tell me a little about the lifestyle. What's it like to be a million-selling author but in the kids book market? Are there book tours involved? How often do you have to get a new book out?

MVF: I guess my situation's a lot different than the standard picture book world. The first thing is that I publish pretty slowly; the most I've ever done is a book a year because the production time is so long. If all you're doing is illustrating or writing children's books, you can really crank them out. You almost have to just to make a living because generally books go right out of print and that's it. Just like in music or anything else, you either have to sell a lot in reprints or make a ton of books that don't sell much. And I've always felt that whatever I produce has to be good enough to stay in print a while, otherwise it's just a waste of my time. And they don't really pay you much, especially when you're just starting off, to just illustrate or write a book. They might pay you $10,000 to illustrate a picture book, but it's so much work to do that many paintings. It might take you a year. Compare that to what you make in advertising, and that's why you don't get so many illustrators getting into kid's books.

As much as people like to think otherwise, the pictures don't really sell the books. The writing sells the books. When you think of illustrators that are really well known, it's always because they're paired with memorable writing. No one would remember [E.H.] Shepard if it wasn't for the fact that he illustrated Winnie the Pooh. And almost always the best-selling children's books, like Sendak or Boynton or Eric Carle, are the people who write and illustrate themselves. Because then you've got a handle on every part of the book.

ST: This must be especially important in children's books, where even the font and layout of the words are part of the design.

MVF: Exactly. Which is why not many people write copy for children's books. Because then the designer ends up having to create the whole book from all these different sources. And it's hard enough to control everything when you're doing it alone, to keep track with the mechanics and the design and the layout.

ST: So do you have any interaction with your readers, either through reading or anything else?

MVF: Oh, sometimes I'll go to my sons' school and talk to the kids or some of the kindergarten classes in my town. But the age group is so young that it's more like story time. When they're a little bit older they can understand the mechanics of it better. But it's a little weird to do a book signing when the kids are three years old.

ST: What kind of work were you doing for magazines early in your career? Are we talking about article illustrations?

MVF: That, and some single-panel gag cartoons. I really wanted to do magazine cartoons, but especially when I just started, I wasn't a very good illustrator. Some of that early stuff really sucks. Even my newer books aren't these great illustrated things.

But I remember reading something about The Far Side; someone said it wouldn't be as funny if it were drawn well. It has that quality of a kid passing you a note in class. And I remember reading cartoons like that but the guy would overdraw the lines and they aren't funny at all.

That's why I said it's the writing, not the drawing. With The Far Side, you could draw stick figures and it'd still be hilarious. With kid's books, 90 percent of it is the writing. That's why I wanted to do the photo books, to prove that.

ST: So what are the virtues of good children's writing? What's good writing for an audience that's too young to read?

MVF: I mean, part of it is that the parents have to get it. But the kids get a lot of it, too. Like in the cat book, they may not understand the pun in "catastrophe," but they get that the cat knocked the vase over. They get the connection between the moving part and the word. And in the illustrated books, I always put the textures in there with a word so the kid can make a connection between the word "fluffy" and the quality of the texture.

That's something that bothers me about texture books. So many of them, like Pat the Bunny, just throw the texture in there without any explanation of it at all.

ST: And yet, Pat the Bunny's just one of those books that refuses to go out of print. Kids love that one.

MVF: I used to work at the company that made that book, but I'd never seen it. I'd heard the title of course, but when I finally saw it, I was like, "Oh my god, this thing sells 250,000 copies a year...what a piece of shit." [Laughs] You've got to be kidding me. Now people just buy it because it's a thing unto itself. It's just one of those things you buy. But if you remember, in the book, there's this little "scratch daddy's beard" thing, and Daddy has this cancer growing on his face. But when that book came out, it was the only one out there like that. I wanted to correct that in my books, though; I wanted to actually have an educational reason for the texture.

ST: Have you done any research, either in psychology or child development, to bolster or come to these conclusions? Or is this all just intuitive responses to a problem you saw in books like Pat the Bunny?

MVF: It's an editorial thing more than anything. And a marketing thing. Like when you look at it editorially and ask, "Does this make sense?" Because my books are about concepts and basic ideas for kids, so when I look at them I think in terms of putting the concept forth. So in the cat book, when you pull a tab and a cat cuddles a bird, there's also a lesson about that; the kid associates that movement with the "nice" cat. When kids are that little, that's really big for them, because it gets them thinking about what the text actually means.

ST: Do you keep up with trends in contemporary children's publishing? Or do you read any other comics for inspiration?

MVF: The art I like looking at for art's sake isn't really related to what I do. I really like some of the anime stuff like Todaro and things, which are all well illustrated and interesting. In terms of what I do, I'm always out there looking at the technological things that happen with kid's books. Because it's always better to work with some design that you know already works rather than come up with one on your own and have it not work out.

But with the picture books, usually they're really disappointing. It makes you think that anything you make can sell... the bar is so low. Maybe that's why mine do so well. [Laughs] It isn't that they're great, it's that there's a modicum of effort in a market that's filled with absolute crap.

ST: Where did the Monday the Bullfrog idea come from? Was that a response to the lack of ideas out there?

MVF: I wanted to do a book about the days of the week, and I was looking at the niche marketing of cloth books. You know, books that are literally made and printed on cloth. And thought, "What would be the best thing here? What would dominate that market and be the quintessential cloth book?" So I went through some ideas where the frog body was cloth and the boards came off the side. But I wondered about making the book the actual animal myself, so I cut up a bunch of stuffed animals and kind of Frankensteined them together for the comp. It got rejected by Harcourt but then picked up when my agent moved to Simon & Schuster.

It's a hard book to sell, because it comes in a box but you really need to open it and read to see what it's about.

ST: Are there any projects like that, ones that go even further from a book structure that you weren't able to get published for financial reasons?

MVF: Oh, I've got plenty of shitty ideas. You know, I wanted to do a book on wheels, or one with a clock on the side. But the thing with these is, the further it's get from a book, the harder it is to sell. Monday the Bullfrog, even for a book, has sold really well, though.

ST: Do you have any more projects in the pipe?

MVF: Well, I never really know whether something's going to work until I do the first comp. Until then, it's the hard part, trying to come up with the ideas. We've got a farm book, a photo thing, but that's not written yet. And I want to do another illustrated book, but who knows what that's going to be. Until it's comped, I always have a lot of ideas but they can fall by the wayside. Half the time the idea won't work at all, so I kick around a thousand ideas and try and make them work. But until then, I try and keep it to myself. The publishing industry is like a freight train, and if you tell someone you've got something then they start penciling it in already. So I wait until I know it can be done.

ST: Do you have any plans to go beyond the age group or illustrate something other than animals?

MVF: I've kicked around a lot of ideas over the course of the years, like doing smaller format books. But my people cartoons look really cartoony, and the things I've written like that are really awful. [Laughs] You know, rhyming verse picture books or whatever. I haven't spent a lot of time with it, though, because it wouldn't be better than anything else out there.

ST: Could you recommend a book, children's or otherwise?

MVF: Well, my favorite children's book (which I still read to my sons) is called Alexander and the Magic Mouse, by Martha Sanders, illustrated by Philippe Fix. I think I draw my alligators like him!