Something was wrong with one of her hands; there was a slight hunch in her back. Her eyes had a sensitivity to light, and even now I can vividly recall a class where she taught from behind a pair of dark glasses; in this particular memory, my favorite college professor resembled Greta Garbo and Joan Didion. I’d describe her as diminutive, but at six foot plus, everyone’s basically diminutive. Even on her worst days, Dr. Eugenia M. Porto radiated a fierce vitality and possessed a wonderful smile. Social systems, institutions, and mechanisms of control were her metier. Michel Foucault, the late French philosopher, was her guiding light; weaving him into discourse, she became brilliant and passionate. Due to scheduling I was only able to take three of Dr. Porto’s courses as an undergraduate—“Seminar in Ethics,” “Third World Philosophers,” and “Senior Seminar: Michel Foucault”—but had to double-check my transcript to verify that I hadn’t taken five or six. My advisor for an aborted Philosophy thesis, she also, briefly, became my friend before vanishing into the world’s ever-widening mystery zone.

Some people have little interest in being known; you’ll scour the internet for them and come up dry, or almost dry; Dr. Porto was like that. From the Washington College alumni magazine I knew that she’d taught there a few years more after I graduated. A decade of Google searches returned “Rate My Professor” entries about her, references to her doctoral thesis—until early last week, when I cast a net and found an obituary dated two years earlier. I read the notice a few times, stunned. I hadn’t heard. I hadn’t known. As it happened, none of the associates we had in common—the philosophy majors, the social justice agitators, and the fellow travelers—had known; all of us were taken entirely by surprise. Sixty-one seemed far too young to die and the depth and breadth of time struck us suddenly with all its unforgiving weight. Any lingering possibility of a reunion dinner or brunch, someday, was gone, and we were left with peeling photographs and warping remembrances. I Googled harder; testimonies proved no less elusive than the scant biographical traces preceding them.

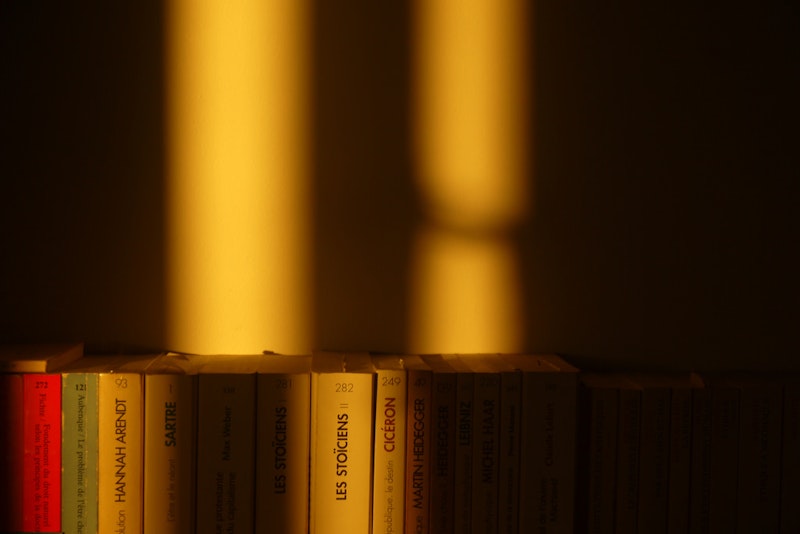

The last time I was in touch with Dr. Porto was around 2000 or 2001. In those pre-Facebook days, she maintained an email list, inundating friends far and wide with revolutionary hyperlinks and insurrectionary quotations and protest details. The final question she asked me was something along the lines of “I didn’t see you at the protest in Washington, D.C. last weekend; why weren’t you there?” Whether or not I replied is a mystery, but by that point I’d begun to slowly transform into the politically-disengaged strawman Dr. Porto sketched for us in one seminar or another: the blinkered automaton who goes to work, comes home, then zones out. (In her example, television was the pop narcotic; in my reality, I was getting high on the internet.) So we drifted apart, and my half-hearted resolution to rework that stalled thesis (“Foucault’s Cigarette”) within the five-year window crumbled slowly. When I wonder what 21-year-old Ray would think of the person 40-year-old Ray turned out to be, Dr. Porto’s anti-establishment tenor is humming through the years.

There is an incompleteness to this remembrance, written as it is by someone who never had the self-discipline to maintain a journal. I’m moving, so the papers of mine she graded and the grainy photocopies of her published papers are buried. Glimpses remain. Dr. Porto joining a bunch of us for a thrift-store adventure in Centerville; Dr. Porto inviting two Cuban refugees who’d spoken on campus to her home (which resembled a large quonset hut) along with several students for a party; Dr. Porto low-key screening bootleg Frederick Wiseman documentaries for us to help illustrate her points; Dr. Porto draped in black robes on graduation day.

In recent years, several Washington College professors have passed. Their passings, for me, were comparable to the deaths of celebrities like David Bowie or Prince: icons who honestly weren’t integral to own my life and development, but were nonetheless key background figures, pillars of a quickly receding past. There is an odd emotion in the remoteness of that sort of mourning, because to an extent the mourning is an act of solidarity or empathy with those who are profoundly affected. The social media parades are impressive, inspiring. Then someone like Phife Dawg or Prodigy dies, and all of a sudden you’re in it yourself. You’re sharing obituaries and tributes and posting YouTube hyperlinks, swept away on an impossibly swift, loud parade float, swimming in communal grief.

Dr. Eugenia Porto—a strong, smart woman who helped teach me to reason, to form arguments, how to view the world from unusual angles, who was a Washington College assistant professor—never got her parade, at least not in any visible, online sense, outside of the family who loved her. She deserves one. Maybe it starts here.