Most mornings in Antrim, New Hampshire are quiet. Once I’d fed the cats at six a.m., I dozed away most of last Saturday’s, drifting off among the gentle sounds of the wind in the trees, the distant baas from the goats of Windfall Farm, about 1000 yards away, or the occasional whirr of automobile tires on Clinton Rd. The noises reminded me of the sound I still miss after nearly 60 years: the clip-clop of the horses drawing Freihofer’s bakery wagons.

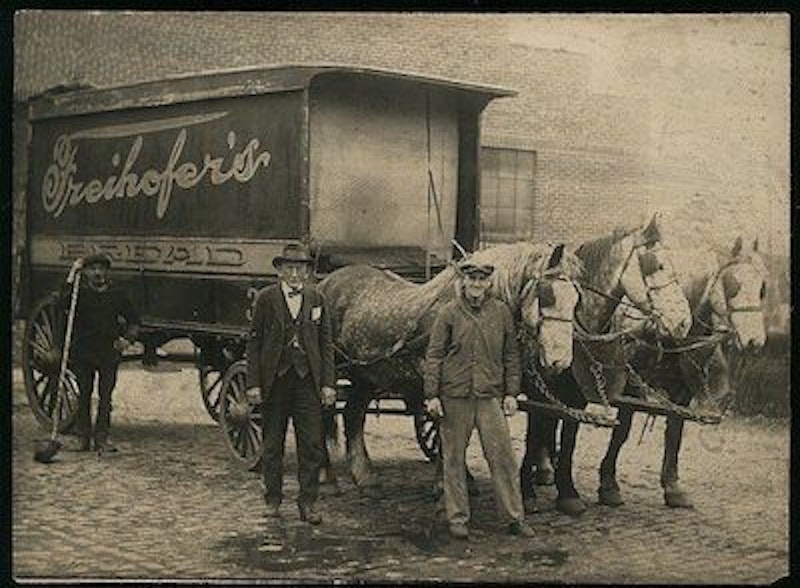

I was born in Troy, New York, and largely raised near Albany. Back then, when America’s local businesses were still run by local businessmen, the Charles Freihofer Baking Company still delivered its wares from its Troy bakeries by horse-drawn wagon, as they had since 1913. Black and red with gold lettering and trim, the wagons came twice a day, bearing hot, fresh-baked bread in the morning, and baked goods—including a once-famous local favorite, raspberry pie in the afternoon. I disliked it: the seeds caught in my teeth. The deliverymen took orders, or one could telephone, or simply leave a Freihofer’s sign in the window so the deliveryman would know to stump up the steps with his basket of goodies.

When our parents took us shopping in Troy, the first sight to our right after crossing the bridge across the Hudson were the huge, orange-red brick stables where the horses and wagons were kept. Sometimes I’d see a horse standing in the stable yard, its tail swishing at flies.

The wagons themselves were as modern as they could be, with rubber tires instead of the spoked wooden wheels of only a decade or two before. They were built by the John Guedelhoefer Wagon Company of Indianapolis, which was still making delivery wagons for bakeries and other companies in Indiana and throughout much of the East, even as it was shifting to building customized truck bodies for chassis provided by General Motors. It only disappeared in 1970 when the last surviving family members, all in their 70s, wound up the business.

The wagons, in fact, were something of an advertising device, of a piece with the firm’s home bread boxes, home window cards, board games, and metal or plastic coin banks in the shape of a wagon.

Back when many local television stations did their own programming, the bakery sponsored Freddie Freihofer’s Breadtime Stories five days a week on WRGB, Channel 6 from 4:45 to 5:00 p.m. Freddy was a waistcoat-wearing white rabbit, a Bugs Bunny manqué: the program was announced by its theme song:

Freddy Freihofer,

We think you're swell...

Freddy, we love

The stories you tell,

We love your cookies, your pies and your cakes,

We love everything Freddy Freihofer makes.

Its host, Uncle Jim Fisk, wore a Freihofer deliveryman’s uniform, told stories, and shamelessly flogged the cookies, cakes, and bread. The audience was full of kids, and although the show was perhaps only a pale imitation of Captain Kangaroo, it was gentle and harmless.

I was often awakened by the clopping hooves, and with the fundamental conservatism of childhood, I felt life would continue in the same way: that we would always live in the big yellow house on Saratoga Ave., and that our bread would be delivered fresh in a horse-drawn wagon, the modern brother of the stagecoaches I watched on Gunsmoke and Bonanza.

None of that would prove true. In 1962, The Times Record, the Troy newspaper taken by my family, ran a front-page story on how the wagons would soon make their last run. Freihofer’s milked the change for all the free publicity they could get. As I’d been reading the papers long before I began attending school, I too was aware of it. Then, one morning, I was awakened by the sound of shifting gears as a red and black truck, with gold lettering and trim, came up the hill toward our house, and the sound of hooves was no more.

Thereafter the old stables housed the horseless carriages that had replaced the horses and their wagons. They, too, passed away: in 1972, Freihofer’s ended the home delivery of its goods. From now on, one bought them in the stores, from the same shelves as Wonder Bread.

Nonetheless, the Freihofer family continued providing a moneyed local leadership with practical business experience. Robert Freihofer, the company’s president for most of the years when I was growing up, ran a successful business while tirelessly raising funds for the Samaritan Hospital, the Center for the Disabled in Albany, and the other local hospitals, charities, and arts centers on whose boards he sat.

Ten years after I’d left the Capital District to make my life in the city, the Freihofer family took the easy way out. In 1987, they sold their bakeries to General Foods, which later sold them to Best Foods, which later sold them to George Weston Foods. While Robert Freihofer lived in the Albany area until his death in 1991, by then his children lived in Boca Raton and St. Petersburg on the income from the capital built up through the work of their ancestors and the men who had worked for them.

Today, the traveling executives who view the Capital District as part of flyover land simply run the firm by the book and not from the heart. By the early-1990s, the recipes had been changed to make the baked goods cheaper—I mean, less expensive—to mass produce, with the usual substitution of corn syrup for the more expensive ingredients used when the business had been family-owned. Now the breads, all produced in a single industrial-scale modern bakery in Albany, all taste the same and the cookies aren’t worth mentioning. As with so many businesses in Troy, once among America’s more important industrial cities, Freihofer’s is little more than a memory, nothing more, perhaps, than colorful labels on interchangeable breads in the local groceries.