The Washington College Black Student Union invited me to attend and speak at a Black History Month event honoring my late uncle, U.S. congressman Elijah Cummings. The text of the speech I gave appears below.

Thank you, Washington College Black Student Union, old friends and new. It’s great to be here with you today at the alma mater that has given me so much during Black History Month, to honor my late uncle, U.S. congressman Elijah Cummings. I very much appreciate your invitation.

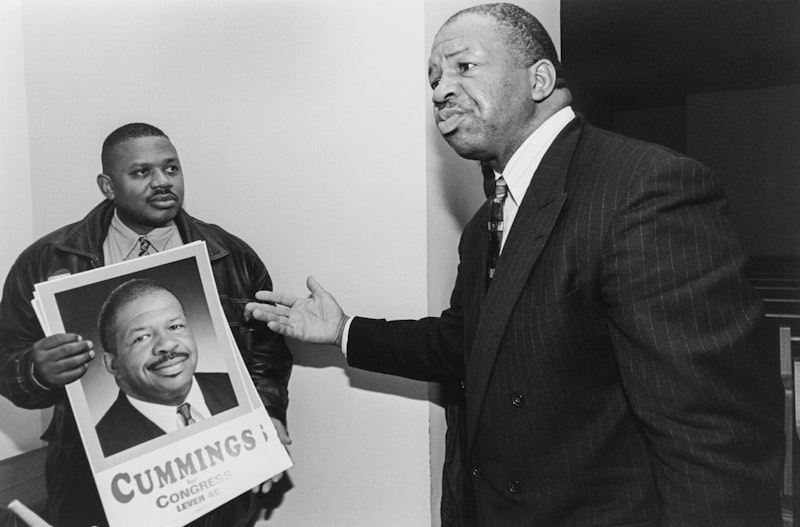

In October 1995, seated in the dining hall, my back to Kent House and Washington Ave., I tore open an envelope from my father and discovered, inside, postcard-size campaign advertisements featuring my uncle Elijah. This was his first run for a seat in the U.S. Congress. The significance didn’t really register with me or surprise me, then; he’d been a member of the Maryland House of Delegates for more than a decade by that point, and this seemed like the next logical step.

About 24 years later and a few days after my uncle’s passing, I floated in the pool at my gym in Owings Mills while a man named Caleb shared his Elijah Cummings story. Caleb, I should note, is a wheelchair-bound man, Asian-American, roughly my age, who refuses to be defined by his disability; friendly, energetic, and enthusiastic, he’s in that pool every single morning, propelled by arm power alone.

Years ago—during the Obama administration—Caleb had relatives coming to visit the country and sought to tour the White House with them. He followed the usual channels for this, repeatedly, and received no response. In desperation, he reached out to my uncle, who was not his congressional representative, for help via email. My uncle wrote back the same day, and arranged a special tour for Caleb and his family on a day when there were no other tours; either Christmas Eve or Christmas Day. He also arranged for a police officer to meet Caleb and his family in D.C. and was able to accommodate his disability. Caleb was extremely grateful for this kindness.

This is one of many, many stories our family heard about Elijah after his death.

Born in Baltimore on January 18th, 1951, Elijah Eugene Cummings was the second of seven children of Ruth Alma Cummings, a church overseer, housekeeper, and homemaker; and Robert Cummings Jr., a manual laborer and former sharecropper. He was a graduate of Baltimore City College High School, Howard University, and the University of Maryland School of Law. From 1983 through 1996, he was a member of the Maryland House of Delegates, serving the 39th District. Following a 1996 special election, he joined the United States House of Representatives, representing Maryland’s 7th district until his death in October of last year; over and over again, he was re-elected handily. There’s a lot of uncertainty in politics, but there was never any real doubt that my uncle would retain his seat, because he delivered for constituents without fail.

He was a loving husband, father, son, brother, uncle, and friend to everyone he met. He founded the Elijah Cummings Youth Program in Israel, and sat on various boards and commissions. At Baltimore’s segregated Riverside pool, in 1962, he was among a group of black boys assaulted for the trespass of wanting to swim on a hot summer’s day.

Uncle Elijah spoke to Baltimore Magazine about this in 2014.

“People were throwing bottles, rocks, and screaming,” he says, shaking his head, “calling us everything but a child of God.”

Upon his death, uncle Elijah became the first African-American lawmaker to lie in state at the nation’s capital.

There’s more, far more, of course; you can find that on your own in articles, profiles, obituaries, YouTube interviews, and eventually, various books. The video of the funeral is lengthy, but offers more personal color, detail, and perspective; I highly recommend that you seek that out.

Right now, though, I want to talk about the uncle Elijah I knew. Unless you’ve lived in the Baltimore area, you were probably most familiar with my uncle from his appearances on television: firmly or forcefully chairing a congressional committee hearing, discussing the news of the day with Rachel Maddow on her MSNBC show. Particularly in the last few years, you watched him there and you felt his power. He was inherently speaking for you, and in turn, you felt powerful; he stood for you and said, eloquently, the things you’d like to think you’d say if you were there in his place. He sought peace, equality, and success for every single American, and he fought for that with every ounce of his being, and more, every single day of his life.

I can’t speak for his constituents; I’ve never resided in Maryland’s 7th congressional district. But to be his relative was to feel this sense of mainstream political representation in an especially personal way, and to understand in a profound, special way how much effort was required to be Elijah Cummings. When you watched my uncle on television, you didn’t know about his various health problems; you didn’t know that he’d likely spent days or weeks confined to a hospital bed for one treatment or another.

His family was proud of him as he was proud to be part of us. And when he was attacked publicly and on social media, we all felt it, and took it personally; attacks on him and his city were attacks on us. When my father, Robert Jr.—uncle Elijah’s older brother—called me early that morning to let me know about my uncle’s passing before it hit the news, one of the first realizations that struck me was that he wouldn’t be able to vote to approve articles of impeachment. Votes—the right right to vote!—meant everything to him, but those votes would have had a special significance.

His mother—my grandmother—implored him, in her final years: “Don’t let them take the right to vote away from us.”

Every Second Sunday, the Cummings family gathers in Baltimore for dinner. Sometimes there are just a few of us; sometimes there are more than a dozen. It’s a way for us to stay close and connected between holidays, to step away from the pressures of work and life, to eat, and laugh, and eat some more. My uncle didn’t show up to every second Sunday, but he came to a lot of them, if only for an hour or two, to check on us, catch most of a football game, and enjoy a plate of greens, macaroni and cheese, and fried chicken in what became his special chair in the space between my Aunt Retha’s living and dining rooms. But first, he had to get into that Edmondson Ave. house.

When I happened to be there, Aunt Retha or Aunt Diane would receive a text that he’d arrived, and my cousin Michael and I would be dispatched to help out. Uncle Elijah’s legs weren’t strong, and he’d lurch out of his SUV. Using a cane and a walker, he’d slowly maneuver along the sidewalk to a first, shallow set of steps, and then up a second, steeper set of steps to the porch, and then into the house. This—to say nothing of the effort required beforehand, as he was always impeccably dressed, in his absolute Sunday best—was clearly a painful, difficult, and humbling experience for him. But he made spending time with family a priority, even if only briefly. We were worth those efforts, just as his constituents and fellow Americans were. Sitting in his chair feels and will always feel inappropriate, in the same way that sitting in his mother’s designated chair, nearby, does.

At family weddings and funerals, and on occasions at Victory Prayer Chapel—the family’s church—Uncle Elijah was often the guest of honor. And I don’t mean that strictly in the ceremonial sense of the phrase. “Local boy made good” is a pop culture cliche, but a local boy made great is exactly who he was—and, he could give one hell of a speech, hitting and grooving in a preacher’s cadences with an intensity and conviction that was thrilling to behold. These speeches were homilies and entertainments that he threw his entire body into, even when he was gripping a dias for support. He had no doubts as to where the stresses needed to fall or when the right moments were to shift from a smile into a stone face that would accentuate the essential humor or seriousness of whatever series of points he happened to be making. He wasn’t politicking in those moments; he was connecting, intimately, with everyone in the audience.

We all, I think, lived for these speeches. And while there was no lack of rhetorical, liturgical, and American political firepower present during his funeral service, I couldn’t help but thinking, five to six rows back from the front, that my uncle’s homegoing was lacking an element that would’ve really put it over the top: namely, an extended coda from my uncle himself.

But that was the past, and this is the present. Let’s talk about the present, about now, and about us.

Elijah’s youngest sister, Yvonne—she’s the aunt who schooled me on Public Enemy and A Tribe Called Quest before I could even drive a car—shared something that her second older brother often liked to say. I’m paraphrasing, but it amounted to this: “Is what you’re doing right now the highest use of your time?”

Life is hard for a lot of us—societally, emotionally, financially—right now more than ever. Racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and religious persecution are spectres that society hasn’t been able to shake off. There are myriad ways to translate our anger and disappointment with the world’s cruelties into action—but that action should be as constructive and positive as we can possibly make it.

Should you write letters to the editor? Yes. Should you write essays, poetry, and stories about your experiences, good and bad? Yes. Should you stay engaged with the political life of your community and country? Yes. Should you champion and agitate for politicians who share your beliefs? Yes. Should you vote? Definitely, in every single election. Early and always.

But I’d implore you—and me, I don’t pretend to be great about this all the time—to work towards the highest possible use of your personal time, and to dedicate that time to helping other people and lifting them up. Be a mentor. Be an ear to bend. Make dinner for someone who doesn’t have time to make it, or drive them somewhere, or perform a common or household task that may not be easy for them but is easy for you. Help a stranger. Share a compliment.

Be a giver—an Elijah, a Caleb. Extend a hand.

I’m a participating social media skeptic, but there’s something to be said for using the medium to broadcast demonstrations of the kindnesses and acts of love that are frequently and mercilessly drowned out by expressions of hatred and division. “The system” is a loaded phrase that’s open to interpretation; I think we all have a general sense of what that means. The system is very often a deck stacked against those who it should support.

I hope that someday that won’t be the case, but for now, we’ll need to be their system, and each other’s system. That’s not as glamorous as being an elected representative or a civil rights hero—something that most of us will never be. But being a leader, and a ground-level hero—a positive, relatable force for good in the world—that matters. We need all the heroes we can get. We all possess the gift of life; let’s make it count, even when making it count hurts.