You Never Had It: An Evening with Charles Bukowski, a new documentary available in “virtual screenings” from Kino Lorber on August 7, is a fascinating time capsule. Charles Bukowski (1920-1990) was a drunken, womanizing, talented, spiritual and hilarious poet of down-and-out Los Angeles (and America). He was probably the last truly famous American poet. It’s hard to think of one today who’d be the subject of a major American film (1987’s Barfly).

The paradox of Bukowski was that he was a poet who wrote about drinking, screwing, the track, despair and fighting, but had a persona that was gentle, mirthful and self-deprecating. It’s easy to imagine his voice, with its gentle lisp, used today for guided meditation audio. When Bukowski talks about “drinking and fucking and drinking and fucking” it’s with a shy smile and playful eyes that won’t always connect with the interviewer. It’s telling that Bukowski, the author of books like Love is a Dog from Hell, Women and Post Office, loved classical music, particularly Beethoven. Despite the dipsomania, he spoke with great precision.

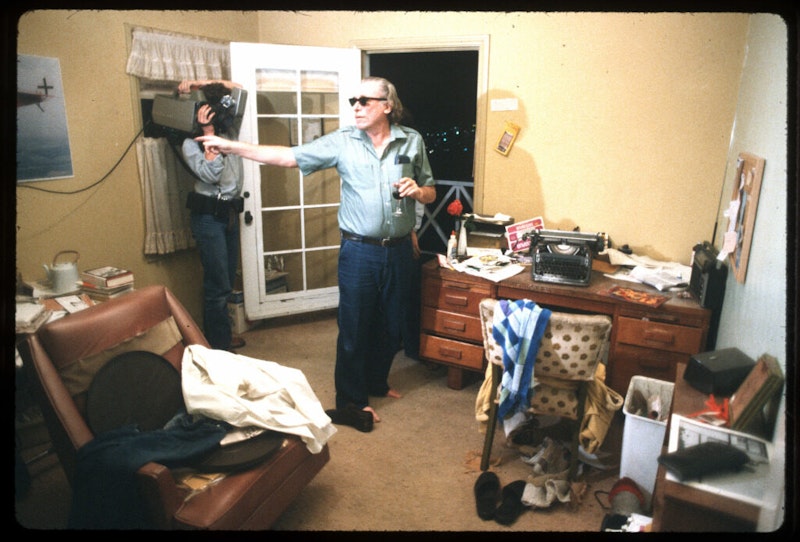

You Never had It was complied from old U-Matic (¾ inch) videocassette recordings made one night in 1981 by Italian journalist Silvia Bizio. Bizio interviewed Bukowski at his home in San Pedro, a seaside community within the city of Los Angeles. Director Matteo Borgardt, Bizio’s son, intersperses new, 16mm shots of L.A.: Palm trees, Venice Beach, Echo Park, the homeless. The most trenchant part of the film comes near the end, when Bukowski ruminates about the “utter grimness” of his childhood. He says he was beaten with a razor strop three times a week “from the age of six to the age of eleven.” Bukowski call the violence “good literary training” because it taught him about pain (and also how to type). He explains that when you encountered “pain without reason” it revealed where “certain sections of life were” and that as a result you can go two ways—traumatized and ineffectual or tough and brave: “When you get the shit kicked out of you long enough and long enough and long enough, you tend to say what you mean.”

Bukowski also foreshadows the world of 2020. “Why is everything sex?” he says to his future wife, Linda Lee Beighle. “Can’t I ride a bicycle down the street without thinking about sex?” And: “Take all these people in the world. They’re more full of hate than they are love. This is our society. Let’s go with the flow, let’s not kid ourselves.”

Bukowski is particularly harsh about other writers. Being a writer and then talking to a writer is “like sitting in a bathtub drinking a glass of water.” To him, “Writers are very despicable people; plumbers are better people.” One senses some jealousy here. Bukowski once turned down an invitation to meet Jean-Paul Sartre while on a book tour in Paris. He tolerated Camus, but only because of The Stranger. Some of this plays well, a rummy rebuke to modern literary school effeteness and ivory tower journalism.

Yet there’s a strong counter-argument that sober, well-fed and reacted writer and poets produce superior work. Browsing the offerings of today’s verse shows that poetry is as powerful and beautiful as ever. The fact that none of these scribes are as famous as Bukowski—even if they’re able to reach the masses—is a problem of our mainstream cultural gatekeepers, not the quality of the work.

Still, it’s questionable whether today’s poets and writers could ever get away with the freedom Bukowski shows in You Never Had It. The swearing, sex, and flowing bottles of wine all reminded me of a comment I saw recently on a YouTube video that depicted teenagers in a 1980s dance club: “They all look so confident.” Bukowski was not a snowflake, but neither was interviewer Bizio, a young and attractive Italian woman (she appears as she is now in the beginning of the film to set the stage). Bizio expertly parries with the poet, drinking his wine, challenging him on several points, and laughing at jokes that might get Bukowski arrested today. What’s captured here is a deep, mystical California evening in 1981, a world of secure and free people without Twitter or cell phones—a world that no longer exists.

Like a lot of young men in the 1980s, I fell in love with Bukowski at one point. His lifestyle no longer holds any appeal, but many of his poems are still wonderful—and his advice in “How to Be a Great Writer” is still solid:

get a large typewriter

and as the footsteps go up and down

outside your window

hit that thing

hit it hard

make it a heavyweight fight

make it the bull when he first charges in

and remember the old dogs

who fought so well:

Hemingway, Celine, Dostoevsky, Hamsun.

If you think they didn't go crazy

in tiny rooms

just like you're doing now

without women

without food

without hope

then you're not ready.