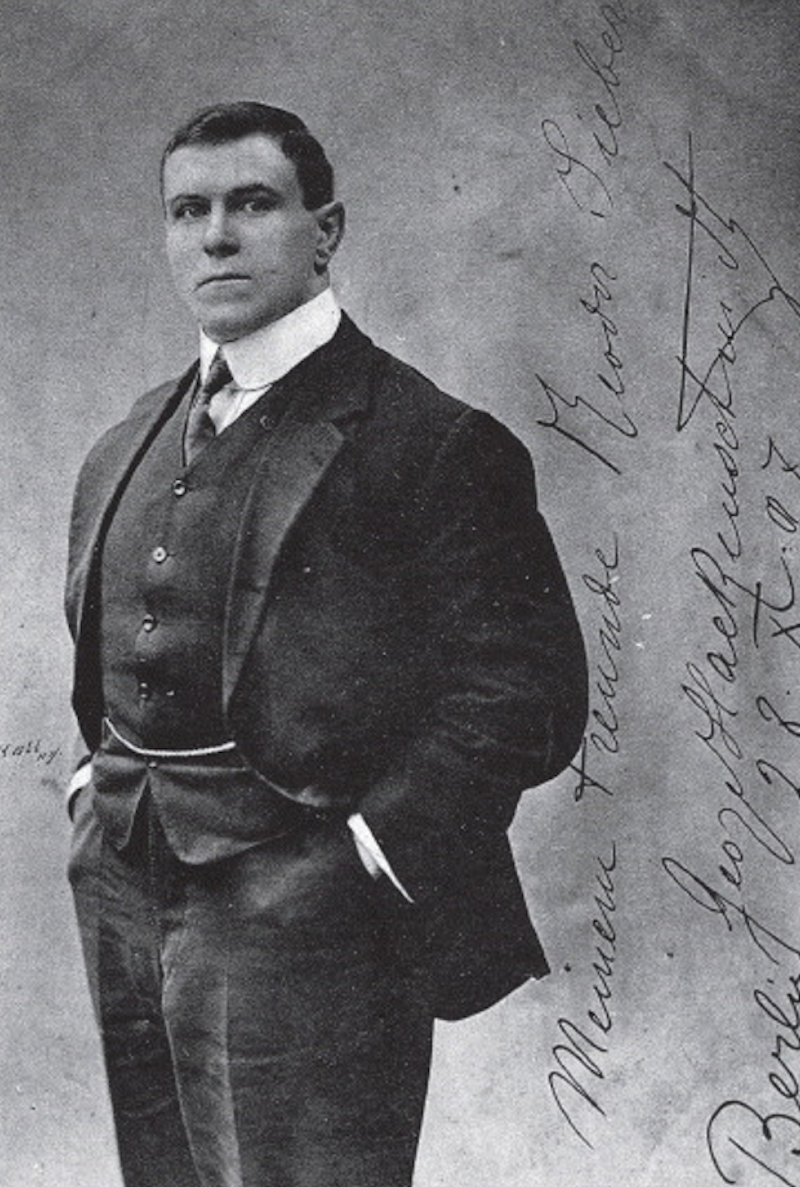

At 5’10” and 220-plus musclebound pounds, “Russian Lion” George Hackenschmidt loomed large in the fin-de-siècle sporting world. The strongman and weightlifting pioneer, often compared to the legendary physical culturist Eugen Sandow in those respects, also dominated on the wrestling mats—at least until he challenged Frank Gotch, the canny Iowa-born wrestler who met Hackenschmidt’s brawn with brains and a willingness to win at all costs.

Of Estonian heritage, Hackenschmidt was born on August 1, 1877 in Dorpat, Estonia, when that region still constituted part of the Russian Empire. He excelled at athletics, benefiting from the training opportunities available to him in the gymnasia associated with the schools where he studied. Although training records of the era remain spotty and difficult to verify, the teenage Hackenschmidt allegedly accomplished some impressive physical feats that would warrant recognition even today, including performing a wrestler’s bridge with 335 pounds placed on his chest and pressing 276 pounds overhand using only one hand.

Although Hackenschmidt had snuck into wrestling exhibitions as a boy, he didn’t begin participating in the sport until his teen years. When he wrestled Paul Pons, a local Greco-Roman wrestling champion, he threw Pons so quickly that his friends assumed the match had been rigged or “hippodromed”—a charge that would follow the “Russian Lion” throughout his career, even though he proceeded to challenge Pons twice more, beating him each time.

As an amateur wrestler at the Reval Athletic and Cycling Club in Estonia, Hackenschmidt proved a quick learner in the Greco-Roman style, which allowed him to rely heavily on his superior upper-body strength, and proceeded to win tournaments all over Europe. His strength continued to increase through heavy weight training, which contrasted with the light, repetition-heavy lifting practiced by bodybuilders such as Sandow. The latter, in Hackenschmidt’s opinion, produced dry, knotty muscles that lacked flexibility and couldn’t handle much strain. By contrast, Hackenschmidt’s preference for lifting heavy weights for a mere handful of explosive repetitions created large, round-bellied muscles capable of the powerful fast-twitch work useful for wrestling and the other sports in which he participated, such as cycling. University of London professor Broderick Chow has written the definitive article on Hackenschmidt’s training and philosophy of life, in which he uses the wrestler as a lens for “working out, though perhaps not working through, the contradictions of modernity.”

By the time Hackenschmidt made his professional wrestling debut in June 1900, he’d gained considerable acclaim as an amateur grappler, overcoming his inexperience with that remarkable power. He lacked polish in the catch-as-catch-can style, having trained primarily in the Greco-Roman form then popular in continental Europe and preferring the upper-body clinch to the leg attacks favored by catch wrestlers.

A clash of styles, however, would prove inevitable. Tom Jenkins, the Cleveland catch-as-catch-can star, traveled to London to face Hackenschmidt in July 1904 and reluctantly agreed to contest the match under Greco-Roman rules. Hackenschmidt won in two straight falls. The pair squared off a second time during the “Russian Lion’s” first tour of the US on May 4, 1905 in a bout for the catch-as-catch-can World Title. Hackenschmidt won the match, held at Madison Square Garden in New York, in two straight falls—what he lacked in knowledge of catch, he compensated for with brute strength and athleticism.

Hackenschmidt’s reputation continued to grow, driven as much by his startling appearance and weightlifting feats as his mat skills. Frank Gotch, the unprepossessing, thick-necked Iowan, was trained by catch-as-catch-can great Martin “Farmer” Burns and represented both Hackenschmidt’s ideal opponent and polar opposite, a shrewd, rubber-limbed fighter who would stop at nothing to win.

Chicago’s Dexter Park Pavilion hosted the April 3, 1908 contest—a box-office triumph and among the first of many so-called “[wrestling] matches of the [20th] century”—and Hackenschmidt lasted two hours and one minute before he gave in, surrendering his title to the slippery, tireless Gotch. Gotch butted Hackenschmidt’s head, thumbed his eyes and nose, and bloodied the heavier man, forcing the “Russian Lion” to concede the bout after his muscles had gone stale and his feet gave out following a futile last bout of exertion to escape Gotch’s feared toe hold submission.

In October 1910, Hackenschmidt returned to the US for a rematch with Gotch, steamrolling top stars such as Charles Cutler and Henry Ordemann to increase fan excitement about his comeback. The much-anticipated rematch took place on September 4, 1911 at the newly-opened Comiskey Park in Chicago. However, Hackenschmidt had aggravated a severe right knee injury during a training session with partner Benjamin Roller that should’ve postponed the bout and would influence its lackluster result.

Hackenschmidt originally injured that knee in 1904 and dealt with periodic bouts of prepatellar bursitis, or “housemaid’s knee,” from then on, which severely curtailed the “Russian Lion’s” athletic potential due to the limitations it placed on roadwork and other forms of endurance training. Rumors would circulate in the ensuing years that noted hooker Ad Santel, an acquaintance of Lou Thesz’s, had received $5000 to injure Hackenschmidt before the match, but no corroboration of this claim exists.

With so much money on the line, Hackenschmidt contested the bout despite his swollen knee, losing quickly by the standards of the time, dropping the first fall in 14:18 and the second in 5:32. The audience of 25,000-plus, paying a record $90,000 at the box office, left with a collective sour taste in their mouths, unsure whether Hackenschmidt had thrown the bout or simply refused to exert any effort to win. Training partner Benjamin Roller, one of the great wrestling minds of the time, commented that he had done his best to get Hackenschmidt in fighting form, but that the former champion simply lacked “gameness,” a quality of mind that couldn't be taught.

After the loss, Hackenschmidt retired from the wrestling business and focused on his writing and speaking engagements. His attempted comeback in 1912 against Stanislaus Zbyszko, which would’ve been interesting given both men’s demonstrated excellence in the Greco-Roman style, had to be scrapped due to continuing issues with his “housemaid’s knee.”

During Hackenschmidt’s lengthy second act as a scholar, which ended with his death at the age of 90 in 1968, the retired wrestler wrote many books ranging from straightforward physical culture manuals to philosophical treatises rooted in the vitalist thought popular during his early-20th century heyday. In its time, his 1908 book The Way to Live in Health and Physical Fitness was widely considered a classic of the physical culture genre.

Today, Hackenschmidt is remembered primarily by sequestered academics like myself and Broderick Chow as well as fitness (“fizeek”) posters praising his physique in some sort of extremely online exercise in empty nostalgia—how can it be anything but empty, when there’s no “home” for these posters to miss? Yet there was so much more, and so much less, to this big man. His capacious body contained multitudes, and we’ve forgotten them all.