Try to imagine a time in the history of fitness when most commercial gyms didn’t automatically include a glorified dance studio with a hardwood floor for the primary purpose of hosting group exercise classes, the majority of which are loosely lumped together under the column marked “aerobics.” The truth is that the concept of aerobics as a sweat-inducing, calorie-scorching activity that confines each of its participants to 16 square feet of space didn’t exist prior to 1971. Long before John Travolta and Jamie Lee Curtis were using an aerobics class as the perfect silver-screen conduit to flirt with one another, someone had to actually invent the concept of aerobics, and then dream up an effective way to deliver on its promise within a cramped and crowded space:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CcaDULcAu3M&t=149s

It just so happened that by the middle of 1967, Major Kenneth H. Cooper of the U.S. Air Force was already credited for making advancements in the areas of cardiovascular training and their relationship to improvements in basic human health. In a UPI article, Cooper explained that his research demonstrated how aerobic exercises like running, swimming, cycling, rowing and cross-country skiing are the best defense for the heart, and the most reliable mechanisms for preventing heart attacks.

“Evaluation of athletes so trained shows that their body reaches a cardiovascular fitness level that far surpasses athletes trained with other types of exercise,” explained Cooper. “It is also unusual for an athlete so trained to have a heart attack, high blood pressure, or any of the medical problems mentioned previously.”

In December of that same year, Air Force Medical Corps captain Dr. David Wells credited the research of Cooper with demonstrating how people who trained in endurance exercises were capable of harder physical labor and adapted more quickly to challenging environments than those who hadn’t prioritized cardiovascular endurance during their workouts. Cooper proposed that aerobic training marked by extended endurance efforts should take precedence over calisthenic training in military settings.

“Human exertion may have finally fallen below the minimum critical level consistent with health,” said Wells, in explaining why he had adopted Cooper’s principles for the men on his base. “Now may be the time when a life-long exercise program is necessary for everyone if he expects to live to enjoy the fruits of affluence.”

Boosted by the adoption of his principles within the greater U.S. military system, Cooper released the book Aerobics in 1968, and included a health assessment test in his book for his readers to take. One reader who scored an “excellent” ranking on his test was military wife Jacki Sorensen, who had been a professional dancer in her teens and was also the former leader and choreographer of the UC Berkeley pom-pom squad. Sorensen had accompanied her military husband Neil from base to base and teaching dance classes to whichever of the airmens’ wives at the Ramey Air Force Base in Puerto Rico who’d accept her instruction. Thanks to her stellar fitness score, Sorensen realized that the frequency of dancing had elevated her into better aerobic shape than the majority of military men.

It was at this point that Sorensen devised and debuted her first aerobic dance class and tested it on the military wives who served as both the students and guinea pigs for her aerobic experiment. Later, after Sorensen’s husband concluded his military service in 1971, she decided to teach her first non-military YMCA aerobic dance class to six students in Maplewood, New Jersey. Sorensen’s students were so pleased with the instruction they received and its corresponding results that they invited their friends to accompany them to subsequent sessions and the class size swiftly grew.

News of Sorensen teaching aerobic dance classes for the sake of health spread throughout the New Jersey region, and in February of 1972, medical specialists at the East Stroudsburg State College outfitted Sorensen with a respiration gas meter designed to measure her caloric expenditure. Sorensen demonstrated the efficacy of aerobic dance as a suitable stand-in for locomotive movements like running and swimming by promptly burning 120 calories in the first-ever scientific test of dancing’s aerobic potency.

With the value behind her methodology now undeniable, Sorensen began a whistle-stop tour of the United States and shared her unique brand of fitness in each location with large crowds composed primarily of women who were eager to adopt an exercise routine that differed from options that were often regarded as masculine. Aerobic dancing classes soon blossomed throughout the YMCAs of the Northeastern United States, and then rapidly expanded across the country.

“It takes the place of jogging and figure-trimming exercises and is specifically designed to improve the cardiovascular system,” elaborated Sorensen to a reporter from The Cincinnati Enquirer in September of 1973. “If a woman expends energy the right way, she will get paid back—she will need less sleep if she is physically fit, and will have more time and more energy to spare. We need to get more women to get out in the open and say ‘Look! I can look and act like a woman but also go out and be active.’”

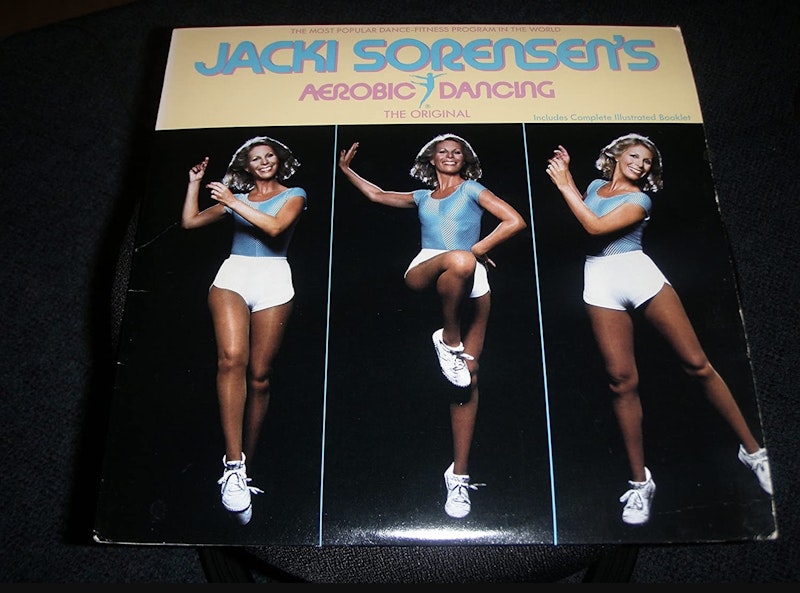

By the end of her second year as the herald of a new era of organized fitness training, Sorensen was already in the process of certifying instructors. Alongside her husband, this pioneer of aerobic fitness incorporated the company Aerobic Dancing, Inc. and by the time Sorensen released her book Aerobic Dancing in 1979, there were more than 2000 accredited aerobics instructors guiding 80,000 students through any of the more-than 400 Sorensen-designed dance routines on a weekly basis. Sorensen explained that she wrote the book to expand the reach of her teachings, and also to accommodate the people who were unable to gain spots in aerobic dance classes, as demand for the materials continued to outpace the supply of classes despite thousands of new available instructors.

“Some people simply aren’t group oriented,” conceded Sorensen in a December 1979 edition of The Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “but they can turn on the radio and do their routines at night, early in the morning, whenever they have a minute.”

1980 advertisement for Aerobic Dancing

By the early-1980s, “aerobics” was already widely used in common parlance as an alternative shorthand term to refer specifically to aerobic dance, and also to any of the variations of aerobics that began to proliferate, like jazz-aerobics and rock-aerobics. When the later-developing forms of confined fitness movement that prioritized larger movements over dancing—like high-impact aerobics and step aerobics—retained “aerobics” in their titles, the term “aerobics” became established as a term to refer to almost any instructor-led system of codified movement conducted in a confined space for a cardiovascular benefit.

So whether you’re a fan of aerobics, or you find them to be an extravagant waste of valuable training space that would be better utilized for jiu jitsu rolling and tire flipping, you can blame it on an Air Force wife from Oakland, California who had the wherewithal to recognize that her lifelong habit of dancing for personal enjoyment had endowed her with greater physical endurance than most of the trained soldiers in her midst.