In the period of time between Reginald Berry of Kansas City, Missouri performing as the Senegalese of Abyssinian import known as Reginald Siki, and Arkansas-to-Michigan transplant Houston Harris initially cast as a South American giant named Bobo Brazil, there was a headlining heavyweight Black pro wrestler who was presented as unapologetically African-American. He didn’t have a theatrical name; more often than not, he simply went by “Johnny.”

For nearly a century, the identity of one of professional wrestling’s Black pioneers was shrouded in mystery. That riddle has finally been cracked, and one of the legends of the squared circle can finally receive the veneration he never received during his lifetime.

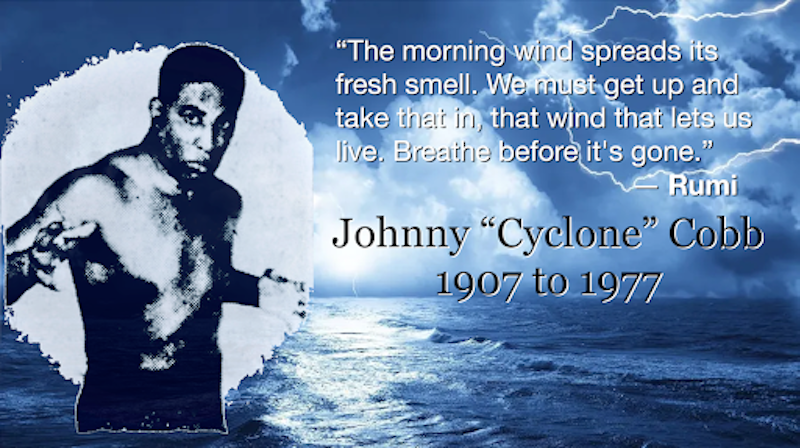

“Cyclone” Johnny Cobb was born in Hallsville, Texas on March 22nd, 1907 to parents Lucious Cobb and Willie Bonner. In the 1920 U.S. Census, Johnny’s listed as the second of three children born to the pair.

Johnny Cobb’s World War II Draft Registration Card

Through the grandchildren of Cobb’s sister, Ida Cobb Swift, it has been confirmed that Cobb lived his final days in Aurora, Illinois, and passed away on August 23rd of 1977. His body was interred at Spring Lake Cemetery in Aurora Illinois four days later.

It was unlikely that anyone around Cobb during those later years was aware they were in the presence of one of the most accomplished Black heavyweight wrestlers of any era, let alone one of the first to be presented as both dominant and African-American, and without having to project a form of exoticized foreign Blackness through his in-ring presentation. Cobb’s family members don’t recall him being married at the time of his death, nor ever having had a daughter. None of them were able to travel north from Texas for his funeral when he passed away.

At 33, Cobb was drafted into the U.S. Army, signing his name as “Johnnie Cobb,” while his draft card listed him at 6’3” and 220 pounds. It was during the war itself that Cobb—while he was stationed in Benning, Georgia and serving as a mess hall cook—gave an account of his civilian life to a reporter from The Black Dispatch. Private first class Johnny Cobb identified himself as professional wrestler “Cyclone Cobb” of Dallas, Texas, and The Dispatch offered the following account of how Cobb’s life first became interwoven with the world of pro wrestling:

“Back in 1931 while living in Dallas, Cobb took up wrestling and has been at it ever since. When the Cole Brothers’ Circus came to town, he was out in the audience. He made his way to the front of the crowd when the fearsome looking “Big Whitie,” the house wrestler, was introduced. All comers were invited to try and throw this mountain of a man. Young Cobb took him on, throwing him not once but twice in a short while. When the circus moved on to the next town, Cobb stepped into the limelight instead of Big Whitie.”

The first clear documentation of Cobb participating in a public display of professional wrestling under his own surname was in Wichita Falls, Texas in the spring of 1934. While the future Bobo Brazil was only 10, Cobb was featured in wrestling events advertising “African Rasslers” in the all-Negro shows of promoter Leo Voss. “Cyclone Cobb” was frequently paired against such adversaries as Kid Jingles, Reckless Red, Killer Smith, Booker T. California, and Yellow Jones.

Prior to the Army, Cobb had already made his first trip to the Midwest in a wrestling capacity, as he squared off against his fellow Black wrestler, the original “Rough” Rufus Jones, in Detroit on Tuesday, October 26th. Once the war reached its conclusion, Cobb’s service records indicate that he almost immediately re-enlisted in the military on September 25th, 1945 and remained in the employ of the U.S. government until September 23rd of 1948.

Despite his commitment to the military, Cobb had apparently racked up sufficient leave time to briefly return to professional wrestling during the summer of 1947. This time, he invaded the wrestling rings of Texas in a heel capacity, competing as Johnnie Cobb “The Colored Detroit Demon” against local Black wrestler “Corn Bread” Brown. Although Cobb was a Dallas native by all accounts, he was billed as the out-of-state heel and was defeated by the undersized Brown in 14 minutes.

Despite these matches taking place in the Dallas area, the attention they generated was sufficient to warrant press coverage as far away as Pittsburgh, with The Pittsburgh Courier noting that this was the first Negro wrestling match to take place in Dallas in six years.

After fulfilling his military commitments, Cobb set out for the Midwest in the spring of 1949, just months after one of the legends who preceded him—Reginald Siki—died of a heart attack, and several years after the two Black Panthers, Alex Kaffner and Jim Mitchell, left to prowl other hunting grounds.

Cobb was immediately heralded as “one of the greatest colored wrestlers out of the South.” Although he’d been relegated to wrestling almost exclusively against Black wrestlers in his home state of Texas, Cobb would square off against a steady stream of non-Black combatants throughout the Midwest, like Reno Lencioni, Stan Karolyi and Spike Peterson. One of his few Black opponents was fellow Texas wrestler Tex Brady, with Cobb emerging victorious during their first engagements with one another.

When the fall of 1949 rolled around, Cobb was already advertised as the “world’s colored wrestling champion,” and by the time he faced Wisconsin Heavyweight Champion Mike Blazer in Green Bay, Cobb was credited with having secured 62 victories in a row during his tour of the Midwest. As the fall progressed, Cobb—whose billed height and weight of 6’4” and 240 were only slight exaggerations in a world where the height of the 6’2” Reginald Siki was boosted to 6’6”—was booked in main-event encounters with world-famous grappler “The Angel” Maurice Tillet, who had twice held the AWA (Boston) version of the world heavyweight championship.

For his bouts with Tillet, the career-plaguing tendency to treat Black wrestlers as “brand-as-required” commodities once again reared itself, as Cobb was touted as a “giant Arizona Negro” to account for the fact that he towered over the 5’9” Tillet, whose body and facial features were contorted by acromegaly. Throughout their feud, Cobb was billed as an Arizonan, a Chicagoan, a New Yorker, or a Minnesotan depending upon the venue they competed in, and it was proclaimed that Cobb had amassed an impressive if altogether fictional record of 245 wins and 14 losses in the preceding six years.

As 1950 progressed, Cobb continued to be marketed as either the “U.S. colored champ” or the possessor of the “world Negro title.” He shared the spotlight with such notables as multi-time world champion Jim Londos, and was an early opponent for a future staple of Midwest wrestling: young Reginald Lisowski before he became known as “The Crusher.”

During the summer of 1950, Cobb returned to Texas and wrestled Tex Grady once again, except this time it was in the home state of both performers, and with Cobb being billed as a northern invader from Philadelphia. The 1950 U.S. census captures Cobb here, living with his wife Lenora, along with his daughter and son-in-law. His profession is clearly listed as “wrestler” on the census form. A few months later, Cobb re-enlisted in the U.S. military and remained in their employment until April 30th, 1951.

Johnny Cobb in the 1950 U.S. Census

In the summer of 1952, Cobb materialized in the wrestling rings of the Midwest, and was promptly promoted as the “world colored champion” once again. During that same year, his Midwestern campaign was interspersed with multiple tours of the Rocky Mountain region, as he wrestled as “Killer” Johnny Cobb in Colorado and Wyoming against non-Black competitors like Jim Blood, Slim Zimmelman, and Masked Cobra.

Johnny “Cyclone” Cobb in 1955

Upon his return to the Midwest, Cobb was still recognized as the Negro heavyweight champion of the world during tussles with Bob “Bonecrusher” Massey and Reggie Lisowski. Despite years of being primarily and correctly advertised as a Dallas native when wrestling in the central United States, Cobb was billed as a Detroiter for his matchups with Massey in the fall of 1953.

Then, just as the careers of future Black wrestling stars Bearcat Wright and Bobo Brazil first gained momentum, the raging Cyclone began a steady decline into a breeze. In 1954, Cobb closed out his final consequential tour of the Midwest while still billed as the possessor of the “Negro world’s heavyweight championship.” From there, Cobb spent the bulk of 1955 wrestling throughout the states comprising the classic Pacific Northwest territory, including Oregon, Idaho and Montana. During this period, he frequently bested Yogi Hussane, “Man Mountain” Dean, and Johnny Dobbs.

While Cobb went untitled during his Northwest tour, he was praised in print as “the best Negro ever to appear in the North country.” Unfortunately, Cobb also had to endure less flattering labels in promotional materials, as Cobb, now 48, was advertised as “the crowd-pleasing colored boy” for at least one of his skirmishes with Dobbs.

When his time in the Northwest reached its conclusion, Cobb ventured back to Wisconsin early in 1956 before competing in his final match on record at the age of 49 against Mike Blazer in the mid-spring.

According to one of Cobb’s few statements on the record, his wrestling career began in 1931 and continued—despite interruptions for wars and military reenlistments—for the better part of 25 years. He was identified in one way or another as the “world Negro champion” for every year he saw activity during the core stretch of that final Midwestern run of his career, from 1949 to 1955. In essence, this provided him with an uninterrupted six-year reign as the recognized “World Negro Heavyweight Champion” in that region, albeit an unofficial one.

Cyclone Cobb struggles to victory against Man Mountain Dean in Klamath Falls, Oregon, 1955

Stylistically, Cobb stood in stark contrast to other fabled Black legends that preceded and followed him. He was described neither as hyperathletic like Siki, nor as a towering and overpowering headbutt machine like Brazil. Then again, the observable bulk of Cobb’s career for which there’s firsthand analysis takes place well after he would’ve reached his physical prime and could’ve best put the strength of his legitimate 6’3” frame to use. All the same, he towered over his African-American contemporary James Mitchell, who was billed at 5’9”, and who was often classified as a welterweight.

Cobb appears to have been a classic mat tactician despite often marketed as a powerhouse who stood head and shoulders over the many of his opponents. During his earliest bouts in the Midwest, Cobb was described as a specialist with “the cobra hold.” In his matches against Londos, Cobb was described as “an exponent of leglocks.” Against Tillet, he was labeled as “an experienced grappler” who was “adept at toe holds.” Against Lisowski, his method of acquiring victory was a sleeper hold. In the Northwest, he frequently defeated his opponents with a “grapevine” body press.

For those drawing real-world equivalents to other sports, an excellent corollary would be the career of Leroy “Satchel” Paige, who enjoyed decades of dominance in professional baseball’s Negro leagues before being invited into the mainstream Major Leagues and becoming a star when he was already in his 40s. When Cobb first achieved stardom in 1949 as the Negro world champion in the post-World-War-II Midwest, he was already 42.

Among the foremost challenges in evaluating Black wrestling history has been the inability to effectively identify who many of the inaugural masters of the performance genre were. While wrestlers like Bobo Brazil, Bearcat Wright and Sailor Art Thomas are rightly praised for their contributions in breaking down racial barriers, they’re often afforded a degree of status akin to Jackie Robinson, as if they were the very first to challenge color barriers, and as if other Black wrestlers hadn’t combated those color lines for decades.

In the case of Cobb, he was among the first truly Black and undeniably heavyweight wrestlers to be booked on an equal status against White opposition while being depicted as African-American, as opposed to an exoticized overseas import.

Tiger Conway Jr., son of legendary Black wrestler Tiger Conway, suggested that Cobb probably missed out on a valuable support system by moving so far north and living outside of his home state of Texas. “The Whites were already in the business, and the Black wrestlers were struggling trying to get to where the Whites were in the business just to get booked,” added Conway Jr. “That’s what all of them were angry about. They could not work. They were sometimes allowed to come in and do exhibitions, but they wouldn’t always get paid. That created a special camaraderie with the Black wrestlers, and they stayed in touch and hung out together.”

Cobb’s grand-niece, Terri Swift Gadsden, who couldn’t recall what her uncle did for a living after his wrestling career ended, was proud to tell others about her uncle’s exploits even if she hadn’t been able to witness them personally.

“We used to tell all our friends that Uncle John was a big-time wrestler, but he lived up in Illinois,” said Gadsden. “No one believed us. We didn’t have any pictures of him or anything to prove it to them, but Mom told us all the time that Uncle John was a wrestler.”

At the revelation that her great-uncle was finally receiving his due, Gadsden was simply happy to be provided with images of “Uncle John” from his wrestling career, nearly 70 years after it had reached its conclusion.

“I just can’t wait to show these photos to the family,” she said.