Amongst the most pervasive and damning stereotypes of 1970s and 1980s pro wrestling, the Black-wrestler-does-headbutts routine blurred the lines between homage and continuation of racist tropes. This was true regardless of whether it was self-sustained by the Black wrestlers themselves, or suggested by bookers, promoters or other wrestlers as simply something a wrestler who “looks like you” is expected to do in order to get over with an audience. Whatever the reason was, everyone from the Junkyard Dog, Tony Atlas and SD Jones to Koko B. Ware and even Tyree Pride demonstrated some semblance of an imperviousness to cranial pain.

In practice, it was a reinforcement of the outdated notion that Black people have thicker-than-average skulls—a myth still reported as fact into the 1930s—mixed with a tacit implication that they also aren’t particularly bright. In practice, none of the aforementioned wrestlers were ever proffered as the epitome of cleverness.

More often than not, the credit (or blame) for the stereotype is laid at the massive feet of Houston “Bobo Brazil” Harris. When the imagery of Brazil is viewed in conjunction with the length and scope of his career, it isn’t hard to see why. If Black people waged war against the racist allusion that they were apes and gorillas, all it would take is one viewing of Brazil’s match from Japan against Jack Brisco—a match in which Brazil messily consumes a banana both before and during the match while headbutting Brisco into oblivion—to convince you that no Black wrestler ever worked harder to reinforce it.

Where did Bobo Brazil’s shtick of obsessively headbutting an opponent into oblivion emerge from? Was that cliché always the derivation of the box-office successes enjoyed by a performer who in his earliest years was provided dueling points of origin in the jungles of both South America and South Africa?

The answer to the question is either “no,” or at least “probably not.” Much of the inherent complexity of evaluating Black wrestling history through an accurate historical filter can be blamed on an absence of data. Due to the overwhelming number of pioneering Black wrestlers with career histories that are either unreported, underreported, or unknown, it becomes much tidier to latch on to those performers whose career histories are the most well-researched, and assume they were the originators of the core components of their routines.

Wrestlers like Bobo Brazil, Bearcat Wright and Sailor Art Thomas have become figurative Jackie Robinsons by default, as several Black grappling stars from the 1930s, 1940s, and even earlier, have unfortunately been forced to take a backseat to those whose ascendance was enhanced by the advent of television.

The King of Bad Men

The birth of the headbutt as a tactic of choice for Black wrestlers began to take shape in the home state of Bobo Brazil when he was only 13. In 1937, a Malden, Massachusetts native whose real name was Joseph Alvin Godfrey made a fresh entry into the Michigan’s wrestling scene, and debuted as “Rough” Rufus Jones of New York City. However, his label as Detroit’s newest “Negro” star from the Northeast didn’t last long. Within weeks, Jones was billed as “an unethical wrestler” from “Red Run, Georgia.”

While Red Run was fictitious, it’s possible that its name was selected for the reason that a “red run” in mountain sports implies that difficult skiing—or in this case, tough sledding—awaits those who dare to tangle with the terrain. A likely reason for the selection of Georgia as the location for Red Run is because Godfrey’s mother Lillian was a Georgia native, as reported by the family’s 1920 U.S. Census entry.

1920 U.S. Census Record of Joseph Alvin “Rufus Jones” Godfrey

Jones made quite an impression during his first month in Michigan. Within two weeks, The Detroit Free Press was already reporting that Jones had fouled young Babe Kasaboski so much during their match at Detroit’s Arena Gardens that the venue’s fans got fed up and stormed the ring to intervene.

Throughout the summer and fall, Metro Detroit newspapers fleshed out the fictional backstory of the 23-year-old Jones. He was an ex-minister-turned-wrestler who hailed “from the cotton fields of Georgia.” He’d been wrestling on the carnival circuit since the age of eight, and had engaged in more than 1000 matches by the time he’d reached Detroit. His repertoire consisted almost exclusively of roughhousing tactics, and he had a special weapon at his disposal—a “flying headbutt maneuver.”

If there was ever a place where roughhousing tactics would make someone a viable main-eventer, it was Detroit during the era preceding the formation of the National Wrestling Alliance. While Jones was relatively small in stature—legitimately measured as standing only 5’7” and weighing 196 pounds on his World War II Draft registration card—he was turned into an instant main-eventer as a “light heavyweight,” and set local attendance records during his feud with the thickly eyebrowed Bull Curry. A crowd of nearly 4900 fans packed themselves into Detroit’s Arena Gardens to watch two unmistakable heels batter one another in a contest for what was unofficially billed as “the mat devil championship.”

From there, in a wrestling territory bereft of true championships, Jones feuded with fellow heel Abe Greenberg and was crowned “King of Bad Men” when he emerged victorious from the struggle and cemented his position as arguably the foremost main-event wrestler in Detroit. Then, as 1939 rolled around, Jones began to debut in other states around the Midwest, often touted as a “The Georgia Negro Bad Boy,” but sometimes labeled far more accurately as a Boston native.

Head-to-Head Encounters

It had already been printed that Jones’ headbutting prowess had baffled his opponents, but it was through the descriptions of Jones’ exploits outside of Michigan that his headbutt-focused offense was brought into a clearer focus. In Racine, Wisconsin, Jones earned the unflattering nickname of “Knothead” by battering Dizzy Davis into unconsciousness with a series of headbutts. The writer from The Journal Times described the scene:

“The colored boy didn’t use his head until the first fall had progressed for quite some time. Dizzy had been up to his usual tactics of hair pulling and use of the ropes, and it finally got on the wrong side of the dusky lad’s skin. At the first opportunity, Jones grabbed Davis by the ears and soundly rapped him on the head using his own noggin as a battering ram. Davis took about five good solid knocks like that and then went down on his knees. He got up once more, and again Jones battered him down by socking his head against Davis’. This time, Dizzy stayed down for the count.”

Of course, there was a second fall to the match, the conclusion to which the reporter also narrated:

“When the referee untangled the two, Jones cracked Dizzy once again with his head. Again and again, he pounded his solid head like a sledgehammer against Dizzy’s head, battering him to the floor. Then he picked him up and pounded some more, until the referee raised the colored boy’s hand in victory.”

Vividly described here are the infamous roughhouse tactics of Rufus Jones, which consist predominantly—and almost exclusively—of headbutt-oriented attacks. In successive editions of The Journal Times, it’s said that Rufus “Knothead” Jones “... uses his head when he wrestles, but not in the manner others do. Rufus uses his head as a battering ram to beat his opponents to the floor by bumping his head.”

Joseph “Rufus Jones” Godfrey’s World War II Draft Registration Card; legendary wrestling promoter Fred Kohler is listed as his employer

As the 1940s progressed, Jones was treated as nothing less than a main-event wrestler throughout the Midwest, and coverage of him nearly always focused on the cranial chaos he wrought. In Sheboygan, the paper printed that the headbutt of Rufus “is a thing to be feared.” In Sandusky, Ohio, a reporter from The Sandusky Register wrote about the questionable legality of Rufus’ use of his head when he stated, “Featuring Jones’ attack is the headbutt. The blow is said to be legal, and although it is said to be ruled out in some states, he resorts to it in states where it is permitted and invariably knocks his opponent out. From that point on, it is an easy matter for him to win.”

In Muncie, Indiana, Jones was described as both a former Boston College football player and the owner of “the world’s colored light heavyweight wrestling title” who makes “remarkable use of the headbutt.” In fact, Jones’ use of the headbutt became so prolific that it became a conspicuous matter whenever he took steps to demonstrate that he was a well-rounded wrestling technician capable of executing other maneuvers. A 1944 edition of The Dayton Herald reported the following interaction during a Jones match:

“Fans who thought all Rufus Jones could do was butt glimpsed another facet of his wrestling character when Rufus met Gorilla Grubmyer in the main event. He managed a neat leg lock with Gorilla’s foot twisted and reversed and tucked under him; he kangaroo kicked; he perfected a reverse crab. He also butted; that’s how he won the second fall.”

The Wrestling World Turned On Its Head

Jones headbutting an opponent in Medford, Oregon (The Medford Mail Tribune)

When Rufus ventured to the West in 1945, his reputation as wrestling’s foremost volume head-butter preceded him. During one of his early victories in Oregon, the “Negro grappler of Detroit, Michigan” disposed of his Chinese opponent with an unrelenting display of literal head-to-head violence.

“Jones, a perpetual motion of tactics that matched his color and kept a record crowd of 800 in an uproar of resentment most of the time, paralyzed the Oriental with the noggin attack to win the first fall in 16 minutes,” printed The Roseburg News Review.

So popular was Jones’ noggin-knocking barbarity that it attracted emulators from the most unlikely of places. None other than famous clean-wrestling African-American star “The Black Panther” James Mitchell—who in several respects was Jones’ immediate predecessor as the top-drawing Black wrestling star in Michigan and the Midwest—suddenly adopted a headbutt heavy offense when he left the Midwest region, making the “cranium knocker” or “cranium buster” a staple of his offense and bringing it to the East and West Coasts roughly six years after Jones popularized it.

By 1947, Jones had extended his domain of main-event wrestling to the East Coast. In a victory over Irishman Jack Kelley in Portland, Maine, Jones demonstrated the full array of his skills.

“Jones forced Kelley to succumb from the pressure of a reverse arm lock in 2:30, then shifted the attack to Kelley’s head, butting him repeatedly from his own skull until referee Fred Moran stepped in at the eight-minute mark to stop the affair. Kelley was bleeding freely from a gash over the eyebrows,” printed the Portland paper.

Jones was rolling into the 1950s and helping to stretch the territorial boundaries of professional wrestling through the strength of his skull. In the West, where he was billed as the “Negro heavyweight champion,” Jones had become a star attraction in Idaho and Utah. The Ogden Standard-Examiner referred to him as a “sensationally brutal Michigan Negro” who would meet his opponents “head-on.” Unfortunately, what brought the unstoppable career of Rufus Jones to a screeching, tragic halt was an entirely different form of head-on collision.

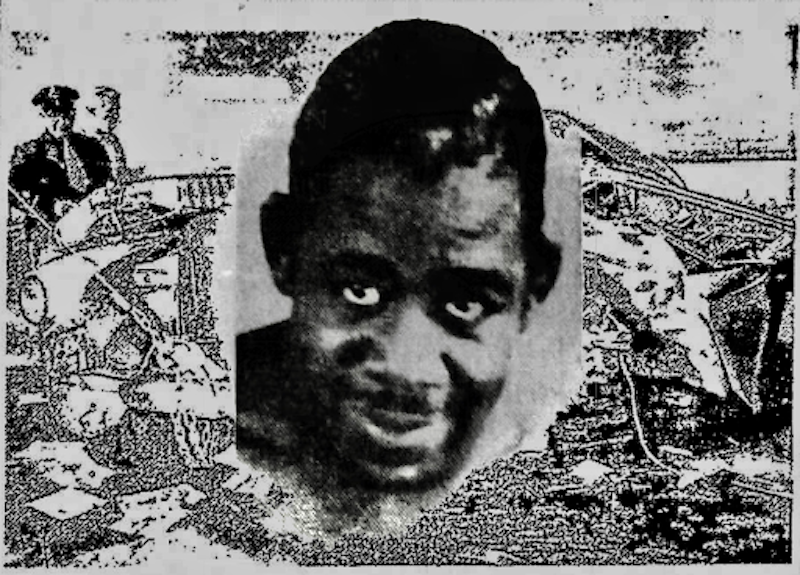

At 8:34 a.m. on the bitterly cold morning of November 17th of 1951, Joseph “Rufus Jones” Godfrey was killed in an automobile collision on Highway 84, one mile north of the forebodingly named “Death Curve” in Ogden, Utah. He was only 38, and was in the midst of a solid 14-year tenure as a main-event wrestler that showed no signs of slowing at the time of his death.

The coroner reported that Godfrey sustained a crushed chest as a result of the collision; the other vehicle plunged 60 feet from the overpass following the collision, but its occupant survived. Jones’ body was returned to his hometown of Malden, Massachusetts and interred at Forest Dale Cemetery. He left behind a wife and no children.

Often Imitated, Then Completely Duplicated

The remains of Rufus Jones Car (Courtesy of The Salt Lake Telegram)

Very little was printed in most locations about the tragic passing of Rufus Jones other than a small announcement of his death in the newspapers of the major cities he wrestled in. Within pro wrestling circles, other Black wrestlers scavenged Jones’ abruptly terminated life and career, relieving him of both his name and gimmick in the aftermath of his passing.

In 1952, another “Black Panther,” Jack Claybourne, would claim to be the rightful holder of the “Negro world heavyweight title” by virtue of the fact that he had allegedly pinned Rufus Jones back in 1943, at a point when Rufus was not campaigning as a heavyweight wrestler. To back his claim, Claybourne presented the Alabama Tribune reporter who interviewed him with a world title belt that had allegedly been presented to him by the New York State Athletic Commission; Jones’ name was one of three that had been etched onto the belt, along with those of Claybourne and “Tiger” Jack Nelson.

Back in the Midwest, Houston Harris had already completed his transition from being “The Colored Giant from Benton Harbor, Michigan” into Bobo Brazil. However, his career would pick up steam in 1952 as he began to use a headbutt-heavy attack that crescendoed into what was first known as either the “coco bump” or the “koko bump.”

Inevitably, Brazil’s signature maneuver would become universally identified as the “Coco Butt.” From there, a stereotype would take shape, as what began as the signature combat tactic of a savvy African-American wrestler evolved into a byproduct of Black jungle savagery and general thickheadedness—in essence, a mental and physical defect masquerading as a competitive advantage.

There was no intended malice in Houston’s adoption of a skull-intensive attack in the development of his Bobo Brazil routine. In fact, as a Michigan resident familiar with the Black wrestling icons of the region, Houston might have been attempting to pay deliberate homage to a departed Black wrestling legend who preceded him.

Far less subtle was the heist by Carey “Buster” Lloyd, whose wrestling career took off after he began referring to himself as “Rufus R. Jones” and adopted a headbutt-replete wrestling style—capped off with his signature maneuver, a charging Freight Train Headbutt—nearly two decades after the original Rufus Jones’ passing.

In this respect, perhaps we can strike some semblance of an uneasy contextual truce when viewing pre-2000s wrestling matches, and we see the stereotype of Black wrestlers as thick-skulled ruffians is on display. On the one hand, it’s disquieting to think that we’re viewing the logical outworking of a routine that became synonymous with racism when it was popularized by an iconic wrestler who appropriated it during a bygone era. On the other hand, we’re also seeing the fading embers of a forgotten Black wrestling legend whose life and career reached a cataclysmic conclusion on a frigid November morning more than 70 years ago.