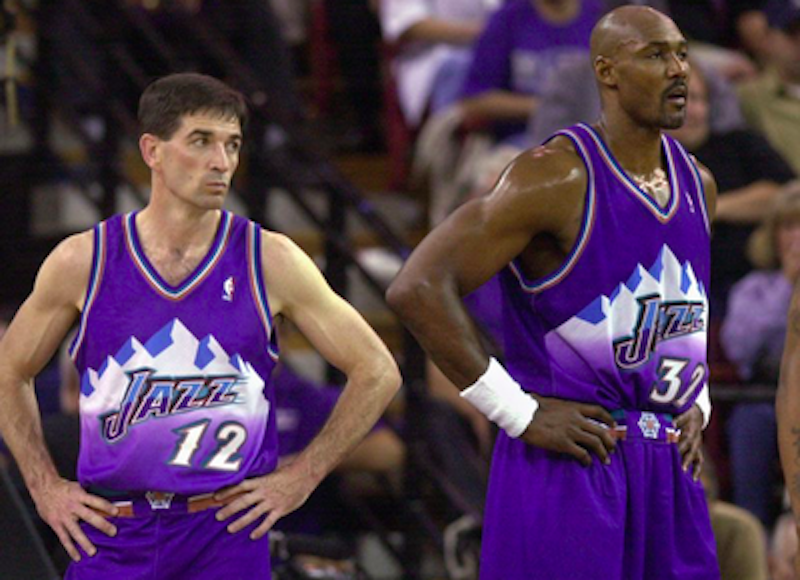

NBA legends John Stockton and Karl Malone of the Utah Jazz are perhaps the most inextricably linked Hall-of-Fame tandem in NBA history. The pair surged to stardom in the two years following the 1986 trade that sent Adrian Dantley from Utah to Detroit in exchange for Kelly Tripucka and Kent Benson. By the end of the 1988 NBA season, both players were stars, and put up eye-popping statistics in almost every game.

In Salt Lake City, the phrase “Stockton to Malone” was delivered so frequently it practically became its own five-syllable word. It’s emblematic of the most successful era in the history of Utah Jazz basketball. It’s also a set of directions on a map, as segments of Salt Lake City roads have been renamed such that traveling from 300 West onto 100 South is officially known as taking Stockton to Malone.

The word “efficiency” has been used to characterize the playing styles of Stockton and Malone. Both players connected with the bottom of the net at a sizzling rate, with Stockton established as the perfect set-up man, and the tall and stocky Malone labeled as the perfect finisher once he received the ball from John. In the world of advanced analytics, where past player performances are scrutinized through a meticulous statistical lens, the two are a pair made in advanced-metrics heaven.

In several respects, the pairing of Stockton and Malone was the next step in the evolution of the Utah Jazz as they transitioned from the era of Rickey Green and Adrian Dantley. Although undersized relative to his position at small forward, Dantley routinely scored 30 points per game while successfully finishing 58 percent of his shots from the field, and often attempting an average of 10 to 12 free throws per game.

In the 1984 season, Dantley was joined on the Western Conference All-Star team by Rickey Green, the NBA’s steals leader from the prior year. During a season in which he averaged 2.7 assists per game—usually by trapping or surprising the recipients of passes into the low post. Green also tallied an average of 13 points and 9.2 assists in every contest. He was a reliable shooter in transition, and could hit open shots when Dantley was double-teamed.

In 1984 and 1985, the team struck gold by drafting Stockton and Malone in consecutive years. In Stockton, the Jazz acquired a player who seemed wholly unconcerned with scoring himself, instead preferring to distribute the ball to his teammates, and generally only shooting if he was wide open. Stockton quickly mastered Green’s tactic of double-teaming men in the low post and stripping the ball away from them.

With Malone, the Jazz acquired a power forward who’d take Dantley’s efficient scoring approach to the next level. While Dantley was highly adept and drawing fouls and had very strong legs that helped him to stand his ground against larger defenders, Malone was a muscular, 6’9”, 250-pound juggernaut who opposing players were incapable of keeping away from the rim. Compared with Dantley, Malone had size, strength and height that made it far more likely that he’d successfully convert his shots after opponents fouled him.

In 1988, with the Jazz team finally free of both Green and Dantley, Stockton and Malone took center stage in Salt Lake City. Malone inherited the bulk of the offensive load from Dantley, while Stockton was there to feed him the ball, and distribute it to the rest of the Jazz players on offense without Green around to share any of the ball-handling duties. As a result, Malone quickly joined the league leaders in scoring while nearly matching Dantley’s number of attempted free throws per game. He’d shoulder the bulk of the Utah Jazz scoring duties for the next decade and a half.

When Malone retired, he did so as the second leading scorer in NBA history, behind only Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Meanwhile, Stockton’s per-game assist totals surged to nearly 14 per game that year, in the first of nine consecutive seasons leading the NBA in that category. When he retired at the end of the 2003 season, he was the NBA’s all-time leader in both assists and steals.

As an interesting side note to Stockton’s unparalleled assist totals, they do appear to be, at least in part, the result of some quirks in the offensive system of the Utah Jazz. Due to Utah’s absolute dearth of competent, shot-creating ball handlers outside of Stockton, John was relied upon to run the entire offense, from one side of the court to the other. As a result, in terms of overall assist distribution, these Utah Jazz teams are historically unbalanced. Moreover, because Malone almost never dribbled the ball more than twice, and was able to successfully put the ball in the hoop after being fouled with greater regularity than just about anyone else in NBA history, the Jazz became a veritable assist factory for Stockton over the next nine seasons.

In addition, Stockton’s mind-bending assist totals, while impressive looking on paper, didn’t correlate particularly well with the playoff success of the Utah Jazz franchise. During the first four seasons in which Stockton averaged 13 or more assists per game in the playoffs, the Jazz lost in the first round twice, and lost twice in the second round. During the five-year stretch in which the Jazz lost once in the first round, lost twice in the Western Conference Finals, and then twice advanced to consecutive NBA Finals, Stockton averaged 9.6 assists per game in the postseason.

As soon as Stockton stopped leading the NBA in assists, in 1997, the Jazz made it to their first NBA Finals in franchise history. Again, maybe it’s a fluke, but it’s interesting that the Jazz achieved their greatest successes of the Stockton-to-Malone era during the two seasons in which the team was the least dependent upon that tandem to blow up the stat sheets. Another interesting fact: Only three players have ever led the league in assists and won the NBA Championship in the same season—Bob Cousy, Jerry West and Magic Johnson. If the Jazz had won the title in either 1997 or 1998, that wouldn’t have changed.

That aside, if Stockton had only produced at his lowest assist-per-game average during the 11-season stretch from 1988 to 1998, the offensive numbers he would’ve generated would still be Hall-of-Fame worthy.

The question has been commonly asked on message boards and YouTube comment sections about who needed whom the most. For whatever reason, whether it’s in an effort to vault John Stockton above the perception that he’s disrespected or historically neglected despite being the NBA’s all-time leader in assists and steals, the more common approach of Jazz fans forced to choose between the two players seems to be that “Malone didn’t make Stockton; Stockton made Malone.”

Of course, because the careers and ascensions of both players correlate almost perfectly, and because they were figurative iron men, there are very few cases where we can make projections about a world in which Karl had to function without John, or vice versa. However, that doesn’t mean the rare cases in which they didn’t share the floor together aren’t worth analyzing and evaluating to see if some worthwhile information can be extracted from the process.

1989: With Karl Malone sitting out the last two games of the regular season, Stockton filled up the stat sheet on April 21st, putting up even more points and assists than he typically would, with a 19-point, 20-assist effort. However, during a season in which Stockton shot nearly 54 percent from the field, he was uncharacteristically cold, going five for 14 from the field, and one for four from three-point range. Stockton’s four three-point attempts were the most he’d ever attempted in a single game up to that point in his career. Eight of his points came by way of the foul line.

The next night, Stockton’s shot was once again off from his seasonal average, as he shot 40 percent from the field, scored 10 points and recorded 10 assists, while connecting on two of five shots in 24 minutes of action during a comfortable win over the Golden State Warriors.

1990: Stockton missed consecutive games twice in 1990, and the Jazz went .500 during those four games. In the first game, on November 22nd, Malone scored 33 points, recorded four assists and shot 61 percent from the floor in a loss to the Orlando Magic. Without Stockton on the floor, the Jazz were collectively one assist shy of their season average of 27.

Three nights later, the Jazz lost to the Lakers, but Malone was similarly brilliant, scoring 31 points, tallying another four assists and matching his efficiency from the prior game by shooting 61 percent from the field. Later in the season, Stockton was out for two February games, both of which were Jazz wins. On February 7th, Malone scored 26 points on 56 percent shooting, the Jazz had four players in double figures, and they beat New Jersey with the team combining for 26 assists. The next night, on Valentine’s Day, Malone had an uncharacteristically poor shooting performance in a blowout victory over the Charlotte Hornets. The Mailman tallied 15 points, 14 rebounds and five assists, but connected on only 33 percent of his shots from the floor.

1992: On December 17th, Stockton played his sole game of the season without Malone. And, during a season in which Stockton shot 53 percent from the floor, he was ice cold, connecting on 20 percent of his shots while recording 13 points and 13 assists in a blowout win over the Hornets.

1998: Following his first MVP season, and a season in which the Jazz won the Western Conference Championship, The Mailman was forced to begin the 1998 campaign without Stockton. In 18 games without him, Malone averaged 25 points, 11 rebounds and 3.6 assists per game on 52 percent shooting from the floor. His season averages in those categories would end up at 27 points, 10.3 rebounds and 3.9 assists per game on 53 percent shooting. Despite Malone’s steady production, the Jazz won 11 games and lost seven during that stretch without their floor general, and reeled off 51 wins against only 13 losses after his return. Later in the season, with Malone suspended during the Jazz team’s April 10th victory over the Clippers, Stockton scored nine points and recorded four assists in 22 minutes of action. He also connected on four of his eight field goal attempts.

1999: As the two-time defending Western Conference Champions, the Jazz took the court without Malone against the horrendous Vancouver Grizzlies. Stockton was the picture of scoring efficiency, hitting five of his six shots, and finishing the game with 12 points and 11 assists in a victory for the Jazz.

2001: In a phenomenal game, the Utah Jazz obliterated the Denver Nuggets by 38 points without their go-to guy on the floor. Stockton hit six of his eight shots, and netted 13 points to go with five assists. The story of this game appears to have been the balanced scoring performance of the Utah Jazz team. In The Mailman’s absence, six Jazz players scored in double figures, and two others missed the double-figure mark by only one point.

2002: The Jazz played two games without Malone over the course of a month. On March 15th, Stockton tallied 14 points and 10 assists on a five-for-nine shooting performance in a win against Detroit. Then, on April 5th, Stockton scored 20 points and distributed 10 assists while connecting on seven of 13 shots in a loss to Sacramento.

2003: In the final season of his career, and in the last game in which he’d compete without Malone, Stockton finished with 10 points and six assists in a November 6th loss to the Detroit Pistons. He made four of his 10 field goal attempts.

When considering the information, the position that it was easier for Malone to maintain the statistical quality of his performance in the absence of Stockton, and not the other way around, iseasier to take. The sample size is larger and easier to evaluate.

During the four games Stockton missed from the 1990 season—during the era of some of the duo’s most jaw-dropping statistical outbursts—Malone averaged 26 points and nine rebounds during the four games Stockton missed, while shooting 52 percent from the floor. This may appear to be a significant deviation from Malone’s season average of 31 points per game on 56 percent shooting, but there are some weird outliers to consider. In the final game of the set, Malone had an incredibly rare 33 percent shooting night, where he only put up half of his average scoring output. Even stranger, the Jazz won the two games in which Malone was the least impressive, and lost the two games in which he was statistically brilliant.

Unquestionably, the largest source of data for judging the two players when they were forced to play without one another comes from the 1997-98 season. In the 18 games Malone played without Stockton that year, the difference between his stats from those games and his averages from the season as a whole were negligible. On the other hand, the caliber of Stockton’s performances when competing without Malone is trickier to evaluate, but it may indicate an increase in John’s true point-guarding skills over time. In his first two games without Malone during the pair’s most productive era, Stockton filled the stat sheet admirably by averaging 14.5 points and 15 assists, but made only seven of his 19 shot attempts, connecting on 37 percent of his shots from the floor. The next time he played without Malone during that general era, he scored 13 points and tallied 13 assists, but connected on only two of his 10 shots. Taken as a three-game sample size, which admittedly, isn’t much to go on, Stockton put up averages of 14 points and 14.3 assists on 31 percent shooting.

Later in his career, when he was no longer leading the league in assists or having as many high-assist outbursts, John seemed to fare far better when playing without Malone later in his career than in the beginning. In his final five games without Malone—which resulted in three wins and two losses—Stockton averaged 12.8 points and 7.2 assists on 58 percent shooting. The assist numbers aren’t as eye-popping as they once were, but the shooting efficiency is superlative.

There are several reasons why this might be the case. On the Jazz teams from the late-1980s and early-90s, many of Stockton’s open looks came as a direct result of Malone being double-teamed. Without Malone on the floor to act as a decoy, and in the absence of other Jazz teammates on the floor capable of dribbling their own way into quality shot attempts, Stockton had to deal with a higher number of his shots being contested. In later years, on versions of the Jazz with a wider variety of shot creators, John could more easily score within the flow of the game, and without being dependent upon Karl to draw attention away from him.

As far as the success of the Utah Jazz franchise is concerned, the Jazz had a winning percentage of 66 percent when John played without Karl, and 59 percent when Karl played without John.

When evaluating the bulk of the data, three things are abundantly clear. First, The Mailman was capable of delivering under any circumstances. If a teammate—Stockton or otherwise—was able to get the ball to Karl Malone, it was going in the basket more often than not. Second, despite the obvious, assist-column-filling advantage of playing with an unstoppable, reluctant-to-dribble forward like Karl Malone, John Stockton was more than capable of filling the assist column without The Mailman on the floor. There’s more than enough evidence to support that fact.

No matter what the statlines of Karl and John were as solo acts, the Utah Jazz needed both of them to climb to the heights they reached. Even if neither was at their statistical peak when the team made it to the NBA Finals, it shows you that there’s far more to playing successful team basketball than individual statistics.