Several weeks ago I wrote a column proposing a radical change for the lowly Baltimore Orioles, one that would energize the franchise in particular and Major League Baseball in general. I’ll return to that idea below, but in short: the Orioles could make history and boost its fortunes by fielding an all-black team—padded at the start by other POC, since only eight percent of Major Leaguers are African-American—which would not only excite the city of Baltimore but entice young black athletes who’ve chosen football or basketball over baseball. It’s worth noting that 50 years ago, the World Championship Pittsburgh Pirates made history by fielding the first all-black starting lineup.

Last weekend, the Orioles gave up 47 runs to the wild-card contending Toronto Blue Jays—amazingly they beat the Jays in one of the four games—a new level of ineptitude at the ongoing Camden Yards nightmare. Embattled O’s manager Brandon Hyde acknowledged the carnage after Sunday’s 22-7 loss before not even 9000 spectators, but underplayed the enormity, saying, “[The Jays are] a good-hitting team, and we’ve got to pitch a little better.” True! Try about 10 times “better.” I was watching the Red Sox/White Sox game on Sunday, an eventual 2-1 win for Chicago, and NESN’s “color commentator,” the beloved (at least in New England and Oakland) Dennis Eckersley, hearing of the Orioles score, simply said, “What’s happening in Baltimore is criminal.”

In a September 2nd article for The Baltimore Sun, authors William G. Tierney (Dodgers fan) and Daniel J. McLaughlin (Orioles fan) proposed their own fix for struggling (or “tanking”) franchises like the Orioles, Diamondbacks, Pirates and Marlins. I found it completely wrong-headed, but the effort was at least interesting. They write: “Baseball is at an inflection point. Both the game and the season take too long, and many useful suggestions are being made about how to remedy that. The sport’s biggest problem, however, is perennially bad teams.”

As a serious fan, who follows the sport from spring training until the end of October, I don’t find the season too long at all (the final regular-season game portends cold weather, snow, much less daylight and the dispiriting months of January and February), or, for that matter, individual games too long. I hate the seven-inning doubleheader rule imposed last year, and in theory at least don’t like the automatic runner on second base in extra-innings games. That the National League still hasn’t accepted the “designated hitter” is a head-scratcher, and you’d think the Players’ Union would lobby for it to extend members’ careers.

Here’s where the writers lose me (after incorrectly referring to this year’s Tampa Bay Rays as a “Cinderella team,” when in reality, despite a perennially low payroll and atrocious attendance, the Rays have competed almost every year since 2008): “Just as there is a salary ceiling for teams [unless management wants to pay an onerous tax for exceeding the cap], there should be a salary floor. Owners of sports teams are among the wealthiest individuals in the country. If they are unwilling to spend what it takes to field a competitive team, then they should be forced to sell the team to someone who will. Baltimore should have a winner again. With a $52 million payroll the Orioles will never a consistent winner.”

This was written before Joe Biden’s nod-to-socialism mandate that all private companies who employ more than 100 people must require workers to be vaccinated, but it’s the same idea. I agree that sports franchise owners are wealthy (and that they can hoodwink local governments into publicly financing stadiums is condoned larceny) and one would assume they’d like to preside over a winning team. But forcing them to sell is not only (for now) illegal but would set a horrifying precedent. Would the authors also suggest that a retailer or restaurant that’s under-funded be forced to sell?

I’m not an Orioles fan but do live in Baltimore and wish that the franchise’s owners, the Angelos family, would invest more in the team (in fairness, Baltimore has had far bigger payrolls in the past, to no avail, save for a few winning seasons in this century; in 2018 the payroll was $183 million), since it’s beneficial for local businesses that rely on sports traffic and for the city’s morale as well. Even if you’re a lackadaisical fan, or not one at all, a victory parade is an event.

Again, this is why converting the team to one comprised of all African-Americans makes sense, especially in a majority-black city. The knee-jerk reaction to this admittedly Quixotic proposal is that such a change would “re-segregate” baseball, but that’s false. If one of MLB’s goals is to boost the presence of black players, like a generation ago, there must be a starting point. If Baltimore began this process, by exciting young athletes about baseball again, it would spread to other teams.

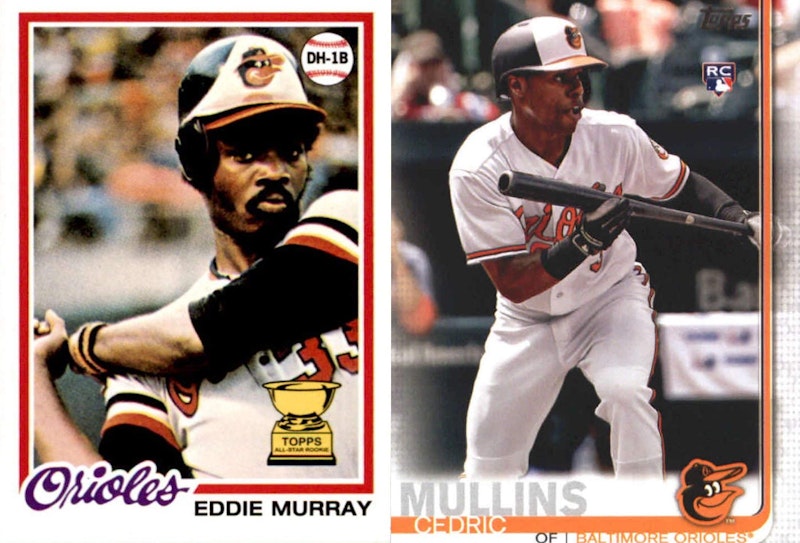

The status of the Angelos family’s interest in the team is uncertain; patriarch Peter Angelos is 92 and in poor health, and when he dies, the family might have to sell to combat taxes. Or, as a liberal family, perhaps they’ll continue. That doesn’t seem likely, though: there’s plenty of minority money in Baltimore, and a new ownership, perhaps with Eddie Murray or Adam Jones as the “face” of the team, like Derek Jeter in Miami, or Magic Johnson in Los Angeles, would work.

The Orioles have a number of players—John Means, Ryan Mountcastle, Trey Mancini and top prospect Adley Rutschman—who’d be trade bait for the likes of Jonathan Schoop, Andrew McCutchen, Marcus Stroman, Justin Upton, Tommy Pham, Dexter Fowler, Justin Heyward, Byron Buxton, Marcus Semien and Mallex Smith, to name just several. In addition, black free agents will be on the market. The O’s already have CF Cedric Mullins as its star. For manager, why not DeMarlo Hale, who’s served as Terry Francona’s bench manager in Boston and Cleveland, but is always passed over when a slot is open. Curtis Granderson might be hired as General Manager; Ellis Burks as the lead MASN broadcaster.

There are logistical hurdles, such as buying out current contracts of front-office personnel and the coaching staff, but a new ownership would know that going in. Swapping out the farm system wouldn’t be easy, but nothing would with such an undertaking. Yet ultimately, such an idea would benefit the Orioles—create the excitement that’s been absent, with a few exceptions, since 1997—and the city. When was the last time a player told his agent, “Put the Orioles on the top of my list. I want to be part of what’s happening there.” As noted above, if this works in Baltimore, it’d filter to other teams, as baseball would become an attractive choice for young athletes.

The Baltimore Orioles are dying: if something as dramatic as I’ve outlined isn’t implemented, chances are the team will be sold to a group who’ll move the franchise to another city.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955