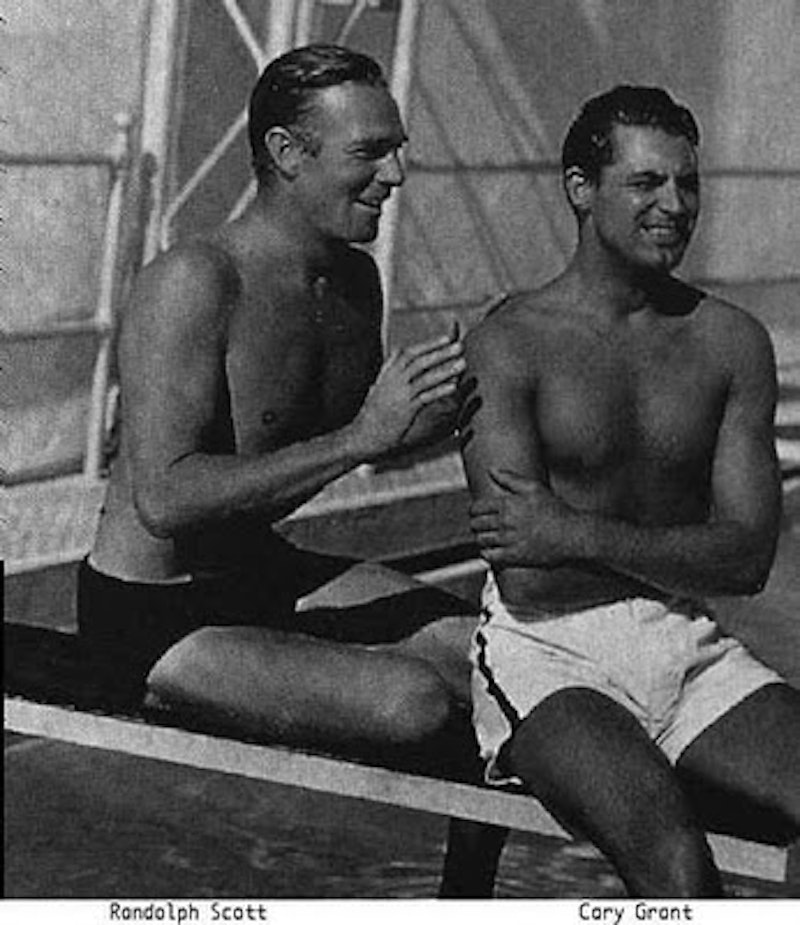

Cary Grant created the best-known evidence that he was gay. He did it in collaboration with Randolph Scott, a great slab of blondness who roomed with Grant for much of the 1930s. The boys were cadet movie stars—starlets, if they had been women—and they posed for their share of fan magazines. Some of these photos are treasured by Grant-as-gay advocates. You catch the boys with matching aprons in the kitchen or chummy and shirtless out by the pool. The pictures aside, Scott and Grant spent almost seven years as roommates. They moved together into a house, then into a pair of apartments, and owned a beach house together. The set of apartments came along during Grant's marriage to an actress; she and Grant lived in one, Scott lived in another. After the actress left, the boys moved into the beach house. At various times they showed up at premieres together, and once (a biographer says) they attended a costume ball dressed as women.

All very suggestive, but not conclusive. The best evidence of Cary Grant's gayness is probably the following remark by George Burns, the ancient comedian who knew Grant from their days on the stage onward. One of Grant's biographers interviewed Burns a few years after Grant's death in 1986. According to the interviewer, Burns mentioned an incident from the 1920s, when Grant was a struggling actor in New York and lived with another man. First, Burns recalled seeing a big argument between Grant and the roommate after a party. Then he seemed to dance away from the subject. Burns said he didn't like “scandal” and added, “I'm not interested in anything that happened yesterday.” Then he said: “And how can you deal with Cary's homosexuality?” Grant and Burns were friends for 60 years.

The Burns quote is the prize, but various acquaintances of Grant made similar remarks. Like the Burns quote, the remarks all popped up in interviews conducted by Charles Higham, who went on to cowrite Cary Grant: The Lonely Heart. The book came out in 1989 and provided print reinforcement for the decades of rumors about Grant's sex life. A more recent biography adds his wife's diaries into evidence. That's the first wife, Virginia Cherrill, the one who found Randolph Scott on the scene. Apparently she and Grant didn't have sex during their 13-month marriage.

I say “apparently” because Marc Eliot, the biographer who read the diaries, is sketchy and indirect about their contents. We're told the married Grant was “totally uninterested” in his wife's beauty “and the promise of good sex that went with it.” We're also told that Grant “had no sexual interest” in his wife and that their honeymoon was a disaster: (Cherrill was “bitterly disappointed by her bridegroom's ignoring her the entire voyage.”) When the marriage ends: “Scott was delirious to have Grant back and chose to pretend that nothing involving Cherrill had ever happened. An inconsolable Grant didn't have to pretend. Nothing had, and he hated himself for it.” Indications are strong that Eliot wants to say Grant and Cherrill did not have sex during their marriage.

But Eliot's book (it's called Cary Grant: A Biography) does not give up its secrets easily. It doesn't even say outright that its material about Cherrill comes from her diaries. One of the endnotes explains that Eliot has read Cherrill's diaries and her notes for a memoir. A second end note lists “the private, unpublished diaries and papers of Virginia Cherrill” among half a dozen sources for one particular section of the book, namely the trip Grant and Cherrill made to England. A footnote says, “Grant's reactions to his initial visit to his mother, and his subsequent discussions about it with Cherrill, come from her unpublished tapes and diaries.” And that's it. Having a solid witness for the adult Grant's first encounter with his mother is very useful. But what about everything else? The encounter took place on Grant and Cherrill's trip to England. What about before and after the trip? All we know is that Eliot feels entitled to speak from Cherrill's point of view.

To take one of many examples, we're told the couple got home and, “To Cherrill's dismay, Randolph Scott was there waiting for them at the front door.” We have to assume that the dismay is sourced to Cherrill's diaries but that Eliot didn't feel like telling us. Or that Eliot just figured Cherrill would be dismayed and treated the matter as given. That's also possible, since he's blessed or cursed with a rambunctious mind. Catch him here: “On a darker note, [J. Edgar] Hoover, who was gay, may simply have fallen in love with Cary Grant and wanted to protect him.” Which is to explain... well, what? The fact that, to Eliot, “it appears strings were pulled” to protect Grant during the Red Scare. Why does it appear so? Eliot doesn't say. The bit appears in his book's acknowledgements. These and the source notes are supposed to be the book's fine print, where you're told what information came from where. But in this book the fine print is more scribble.

Eliot and Higham want to make something dark out of Grant's life, and they go galumphing after their conclusions. Take the non-facts that accumulate around one incident, the filming of The Pride and the Passion. Grant shot the movie in Spain with Sophia Loren and Frank Sinatra. Higham reports that Grant developed feelings for “a young male Spaniard” during the shoot. The source is Melville Shavelson, a Hollywood director who made a movie with Grant and Loren. But that movie was Houseboat, not The Pride and the Passion. Given as much, there's little chance Shavelson was on site there in Spain, thousands of miles from Hollywood. So how would he know about the Spaniard? In the accompanying endnote, Higham explains that Shavelson just happened to know a whole lot about the production.

The book describes Shavelson as Grant's “friend” and mentions that Grant, after getting divorced, bent Shavelson's ear about Betsy Drake (wife number three). At no point does it say that Grant confided in Shavelson about a gay sex life. Yet it still treats Shavelson as an authority on the subject. The director once wrote an unpublished novel about a beautiful Italian actress and a secretly gay film star (“America's Number One screen lover”). The gay star offers the girl everything “in return for her making him a man.” Shavelson said the film star was Cary Grant. Now here's the magic part. A few pages later, Higham tells us that Loren “must have known that Cary's sexual insecurity would make her life a torment, and that his challenge to her to cure him was no basis for a proposal.” What challenge? Shavelson's guess is turned into Higham's fact.

Eliot plays similar tricks. The Higham book has a long quote from Stanley Kramer, director of The Pride and the Passion. Kramer tells how Sinatra bugged Sophia Loren by periodically saying, “Sophia, you're going to get yours.” The director said somebody finally told Loren what Sinatra meant by “get yours,” and she shouted back at him, “Not from you, you Italian son-of-a-bitch.” Eliot keeps “Italian son-of-a-bitch” but drops the “get yours” business. According to him, Loren started shouting because of the way Sinatra had been riding that old queen, Cary Grant. Eliot gives no evidence that this was Loren's motive, not in the text and not in the notes (which add up to just 70 words for the whole chapter). It's a fact because he typed it.

But none of the above means that Cary Grant was straight. Back when a 1930s gossip columnist did a lavender on him, the same item also named Jimmy Cagney and Gary Cooper. With Cagney and Cooper, the talk died away. With Grant it kept going. For what it's worth, the more solid indications of gayness (exhibit A: the Burns quote) appear in the first half of Grant's life. During the second, we have lint like a “mysterious and puzzling” incident (it's also “unsolved and baffling”) that consists entirely of “the late Hollywood producer William Belasco” telling Higham that during the Manson killings Grant was next door visiting “a young male.” Compare that with the friend of Grant's roommate-lover (both men are named) describing the young Grant's habit, when “involved in an amorous occasion with a young man,” of warning off the roommate by playing loud classical music. At least we can see how the friend would come to know this.

As the gay evidence turns squishier, the straight evidence firms up. It would appear, if we give Marc Eliot the benefit of the doubt, that Virginia Cherrill and her husband didn't have sex during marriage. But Grant's third and fourth wives went on record saying they had married sex with Grant and that the sex wasn't half-hearted. In the second half of his life, Grant certainly acted like a heterosexual man with opportunities. Somebody looking for a beard would pick one suitable mate and stick to her. Grant went looking for happiness, and he did so in the vicinity of young vaginas. His third wife was 26 when they married, his fourth wife was 28, and his fifth wife was 30. By that point Grant himself was 77. You get the idea. When a scandal blew up just before his lifetime Oscar, no young men were involved. Instead it was a paternity suit filed by an ex-showgirl, 33. (Higham says there was no sex, Eliot says there was.)

Whether he was gay or straight, Cary Grant wanted two things. He wanted people to pay attention to him, and he wanted them to back off. We never managed the second. Now he's stuck with us, at least those of us nosy enough to read up on other people's lives. Personally, I'd like to believe the waiter who says he saw old Cary Grant and old Randolph Scott holding hands at their table one evening in the 1970s. I'd also like to believe Betsy Drake on the Grant-Drake marriage (“we were busy fucking”). I'd like to believe that Grant found the pattern that belonged to him.