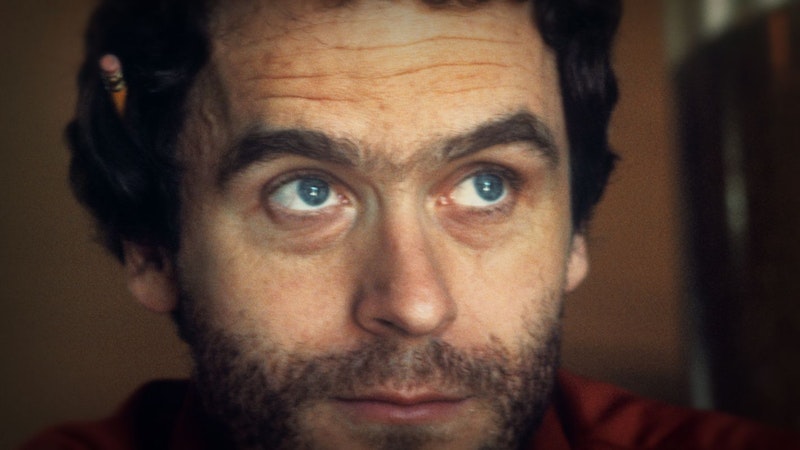

Conversations With A Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes, a new Netflix documentary, is the strangest event in our cultural fixation with true crime. It's a good documentary, but it's also a moral test: how do we reconcile knowing there's evil in the world? How do we deal with something we can see everywhere in our entertainment, whether it's the news or startling shows about serial killers. We have to try to understand whether this is good or bad.

The series has no interest in titillation by way of horror. Creator Joe Berlinger has made a career of true crime moviemaking, so you’ll get a professional documentary, a work of art, in a way. But it's not meant to impress you in the way prestige TV is. If anything, it criticizes prestige TV that glamorizes evil. The series is based on a series of interviews with Bundy by Stephen Michaud, a writer of true crime books.

His takeaway, after listening to Bundy describe his actions, is that he learned nothing. He could no more understand what made Bundy evil afterward than before, because he doesn't want to be evil. The entire series forces you to experience this barrier between good and evil. Whatever's on the other side is incomprehensible, but real. You can see what Bundy did. Everything is shockingly documented in our modern world. But it's still inexplicable. None of us would ever act this way.

So the documentary should be understood as a reproach to a culture that endlessly produces and consumes drama about serial killers, turning evil into a metaphor for whatever a creative or talented type in Hollywood wants to talk about. That's transgression for the sake of celebrity. This documentary, however, isn’t intended to secretly please conflicted liberals. Serial killer shows may be popular, but they offer nothing except a stupid form of therapy. Their account of our souls and society mostly blames evil on people who were insufficiently ideologically liberal to children who then grow up maladjusted.

Instead, the documentary brings up a deeper question: Why are we interested in something we can’t understand? It's because it's happening among us and we can’t help thinking that it says something about us as a society. At some level, we suspect that serial killers are the craziest, most terrifying part of American individualism, a perversion of freedom that we cannot seem to stop staring at.

Acknowledging the horror and moral terror that surrounds evil is what I mean by our loss of innocence. We all accept, for example, that images of extreme violence are now a banal form of entertainment. Most of us don't even think there's anything we can do about it. It's just there. But it's a fact that true crime shocks us and that's a reminder that evil isn’t just a matter of entertainment consumerism. It's a reminder that we're no longer sure we're morally pure.

Since the days of our Puritan founding, we’ve always insisted on our morality. Even today, in the midst of apparent cultural collapse, we’re all convinced we’re moral creatures. Instead of the permanence of evil, we just think people who disagree with us politically have to disappear. Progressives blame conservatives and conservatives blame Progressives, but all agree that we need justice and equality for all and everyone should be treated the same. Neither faction sees that it's chasing after the same vision of paradise as the other. Neither faction in our national conflict think there's any evil within itself—only the other one. So we cannot look into our own hearts.

But when we see non-ideological evil in our society, when someone who looks like any one of us does something monstrous, it’s much harder to still say we're morally pure. Aside from partisanship, we all experience the hopelessness that surrounds evil. When we become aware of this marginal, but terrifying phenomenon that emphasizes personal vulnerability, it's much harder to assign political blame. Mortality beats ideology. Evil in our peaceful society points to our own nature, not to ideological disagreements.

We’re fascinated by evil because we suspect it's inside each one of us. But our public ideology is individualism, which declares each one of us is more or less perfect. Society or someone else is always to blame for anything that afflicts anyone. Since we can’t have a culture or society where people take responsibility for themselves, we're stuck obsessing over how evil arises out of normal life. The only way out is learning that we’ve pushed the ideology of individualism too far. That without a certain education about what freedom is, some might abuse it in monstrous ways and nobody would know until it was too late.

It's hard to even think how we could learn to be good while being free, since we can never talk about ourselves as a society anymore. The “we” is not there. Stories about evil bring that out—the helplessness to do anything when it counts, the terror of individual vulnerability. Where could we go to learn? We have no policy expertise to prevent evil, much less cure it. We don’t have a science for evil. As for our culture, we think of it as entertainment, not education. And the churches are not only mostly empty, but we have more than enough evidence that churches themselves sometimes perpetrate monstrous evil. We're confused as a society.

It's not the end of the world. America’s a peaceful, wealthy nation. Most people enjoy comfort unrivaled in world history. Crime, our first idea of evil, is at historic lows. But our political and cultural craziness signals a problem that also comes out in stories about evil. Practically and theoretically, individualism isn't enough. As a society, we have no response to evil but cycles of denial and morbid fascination. We need to look for more resources in our ways of life—from philosophy and religion to political traditions and traditions of community. Only when we can confront evil as a society will we know we're mostly okay.