Last week I was on the horn with one of my brothers and, as frequently happens when we talk, the subject of media and politics came up. He lives in Bermuda most of the year, and told me that the hotel near his house, where every evening he picks up that day’s copies of The New York Times and Financial Times (he takes The Wall Street Journal digitally), has stopped supplying print newspapers. The distribution company on the island, after 80 years of providing this service, made the inevitable decision that the declining number of customers—people over 50—made the business untenable. My brother was bothered by this: after all day looking at a screen, he likes to read the FT and Times in the more relaxing format of print.

I’m guessing, then, that he missed a Times article in Sunday’s “Review” section that caught my attention. (I read the Times online, except for Sundays.) Written by Pamela Paul, the paper’s “Book Review” editor and author of five books, it was on the subject of boredom, and her conviction (although I’m sure she knows it’s too late) that boredom for children is a character-building, constructive tool that can help prepare them for adult life. I’m not sold on this conceit, but there’s no dispute with her well-trod contention that kids today, usually spurred by “uberparents,” aren’t given the opportunity to get bored and figure out something to do. You read about it all the time: parents slotting every waking hour for their children with sports leagues, music, swimming and horse riding lessons, repetitive SAT tutoring and courses, summer camp, volunteer work and scheduled playdates.

She writes: “Boredom is something to experience rather than hastily swipe away. And not as some cruel Victorian conditioning, recommended because it’s awful and toughens you up. Despite the lesson most adults learned growing up—boredom is for boring people—boredom is useful. It’s good for you. If kids don’t figure this out early on, they’re in for a nasty surprise.”

It’s a debatable argument, the “nasty surprise” bit, but I found Paul’s article worth thinking about, unlike, for example, an atrocious essay a few weeks earlier, also in the “Review” pages, a “humblebrag,” in today’s fractured parlance, by a woman who boasted she’s too busy to answer emails.

As a pre-teen I was more than occasionally bored, especially during the summer, after the initial rush of no school had worn off. Sometimes my friends were busy with their families, or it was raining, which meant no pick-up baseball games; it could’ve been that I’d seen one too many episodes of My Little Margie or Make Room for Daddy, or I’d exhausted the local library’s collection of children’s books about presidents and famous baseball players (mostly by Gene Schoor), or had already run through the Beverly Clearly section. At 10, it wasn’t as if I was going to tackle T.S. Eliot, Wordsworth, or Faulkner.

I once made the mistake of telling my mother that I was bored and she was having none of it: “Bone up on geography!, Build a fort in the woods! Get rid of some old copies of Mad and Boy’s Life!” Two hours later, I proudly told her that I’d organized my political button collection, and that was met with derision: “Oh great, make sure to put that on your list of extracurricular activities for college. Princeton will be impressed.” (Admission to an excellent college, with a scholarship, was really her sole “helicoptering.”) Again, I was 10. (Incidentally, when it was time for college applications, Princeton wasn’t impressed with me, dashing my mom’s dream that one of her sons would attend that school.)

As a teen, I was rarely bored. In addition to a mountain of homework during the school year—four or five hours on a busy night—scattershot jobs around the neighborhood mowing lawns and babysitting, reading several daily newspapers, as well as The Village Voice, National Enquirer, Rolling Stone, Ramparts, and National Lampoon, buying and smoking nickel bags of grass, listening to music, long bike rides and, when I turned 16, cruising around Huntington in our station wagon, weekend parties, sledding in the winter, swimming at the local free beaches in the summer, and discovering Dylan Thomas, Nathanael West, Dickens, Allen Ginsburg, Joan Didion, and the obvious teen favorites Salinger, Hemingway and Fitzgerald, my activity plate was not skimpy.

On one memorable October day in 1971 I walked to Cold Spring Harbor with my friends Mike and Andy for the annual fair in that (at least then) marvelously quaint town. I’d been going to the fair for years with my family; the rummage sales where you could buy cool jackets or hats for a nickel or dime were boss, as was the ham luncheon in the firehouse, and I never tired of seeing the ancient cider presses working, always attracting scads of yellow jackets. Mike, Andy and I roamed around, bumped into my Uncle Pete, who came in from Queens, and he treated us to a few snacks. Around four o’clock we walked home, blitzed on hash, and upon arriving back in downtown Huntington, Andy (who’d started shaving in sixth grade) bought two quarts of beer at a deli and we hung out at Mike’s house. At 16, we were amateur drinkers, and Andy was off his rocker, wobbling around, mooning about a girl in our history class. I paid no mind, until Mike, investigating, rushed out to tell me, “Andy’s barfing and jerking off at the same time! Let’s get him out of here; I’m screwed if my parents show up.”

Perhaps, or perhaps not, an example of making your own fun that Pamela Paul refers to her in article.

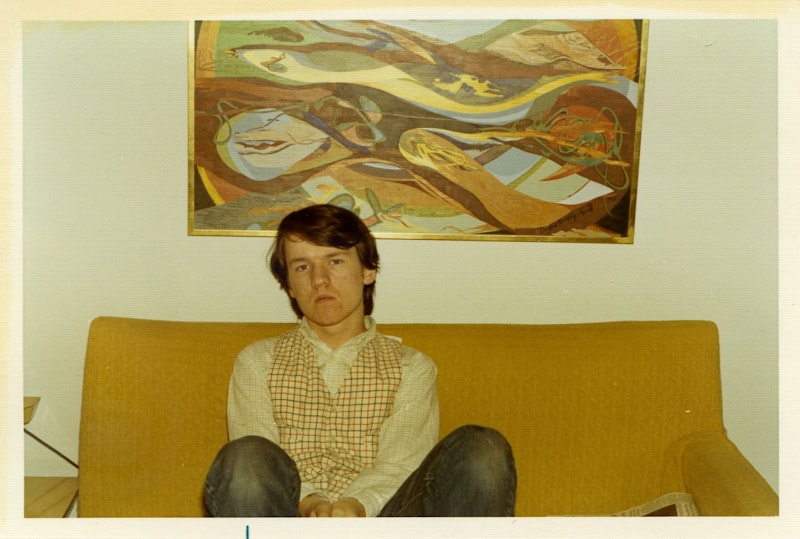

(In the picture above, shot on a tripod in March of ’72, I look bored but can assure you I wasn’t. At the moment the camera clicked I was listening to “Moonlight Mile,” floatin’ naturally, and about to drive over to Halesite to see my friends Elena, Hazel and Ruthe. By the way, it’s crazy to think now that just five years later, the Clash’s “I’m So Bored With the USA” was released.)

Another quibble about Paul’s self-help article. She writes: “Things happen when you’re bored. Some of the most boring jobs I’ve had were also the most creative.” Good for her, but some of the most boring jobs I’ve had were also the most boring. Standing outside as a parking attendant at the Johns Hopkins faculty club for three hours—especially brutal in the winter—was not creative. Working 12-hour shifts at an old folks home in Baltimore’s Roland Park wasn’t bad for the first portion of the day, studying for exams and talking on the phone, but by six p.m. I was shot, and reached into my pocket for the miniature bottles of Cuervo that I’d stashed for a boredom flash.

I’ve no idea if my Millennial sons were frequently bored growing up. I never asked, but the answer’s probably no.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955