Once again I am learning about a media event seventh hand, as if meeting a person by shaking their thigh. Let me open up my lookbook.

Uh oh (Airplane! face). St. Vincent did something. A bad thing. Not the volcano, which did erupt recently, displacing 15,000 people—no, Annie Clark, the artist, the musician, the singer. St. Vincent. She. Did. Something. Bad. Or wrong. Take your pick.

I still don’t know what she did or who she pissed off or offended or praised. I can’t even find the interview “everyone’s talking about.”

I will soon, but first this, from a thread by journalist Alicia Lutes: “i have no idea why, but all of this st. vincent stuff reminds me of a time a fairly famous author said something EXTREMELY OFFENSIVE AND BAD during a video interview and two editorial staffers insisted we cut it preemptively from the interview so as to not make waves el oh el… it just really rankles me how much entertainment journalism is predicated on "not pissing off the people that need the press" which is... not at all how anything even close to journalism is supposed to work!… i think a lot of people think entertainment journalism isn't real and doesn't deserve to be taken as seriously or professionally as the rest of journalism, which is a really bad precedent to set, especially when entertainment shapes our societal worldview in MANY WAYS.”

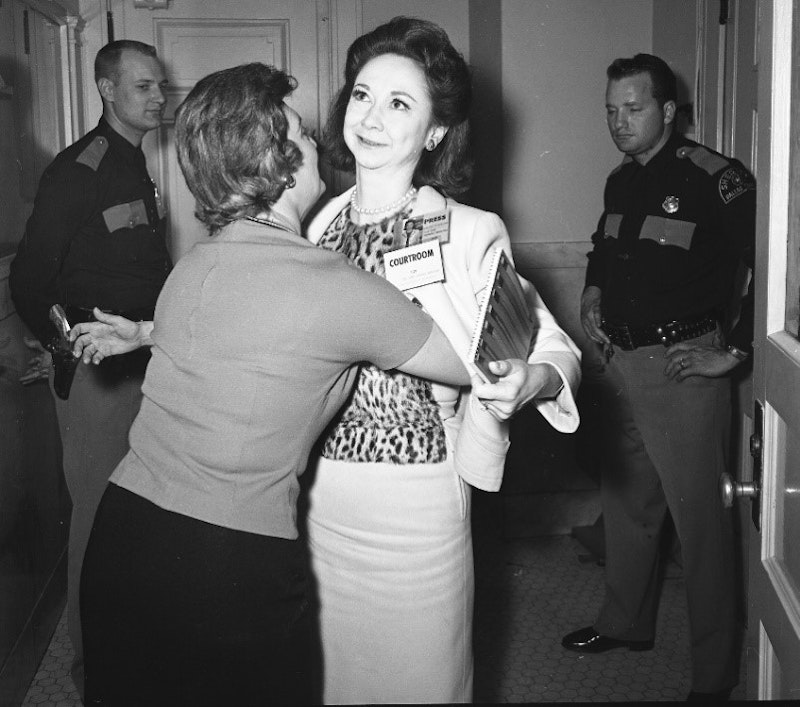

Entertainment journalism has always been virulent, full of lies, and often actively harmful. It’s a short history, and not one dotted with “truth tellers” per se: Louella Parsons, Hedda Hopper, and even Dorothy Kilgallen all ladled and massaged their columns when friendships and marriages required. After all, this isn’t the Pentagon. Look what happened to St. Kilgallen when she refused to let up on her own investigation of the JFK assassination. She lost her access to life. Now, the St. Vincent, Annie Clark, interview.

Fantastic—I love learning about things together, in real time, with you, my dear dear reader. Here we have a very funny story: Annie Clark’s father spent time in prison for “white collar crime,” and, according to Roger Friedman at Showbiz 411, “it’s part of the story of her latest album.” Despite this, Clark killed an interview with writer Emma Madden commissioned by an unnamed outlet, and when Madden tweeted her interview along with a brief explanation of what had happened, it was quickly deleted, although whether this was at the behest of Clark’s PR team or Madden’s own volition is unclear.

From Madden’s post, since archived: “For her last press cycle, [Clark] made her interviewers crawl into a pink box; she would play a pre-recorded message on a tape recorder if a question bored or irked her. I found that quite funny—irresistibly imperious—but I considered it an act of degradation rather than an interesting switch of power. I love famous people but I also find them quite silly, like a Schnauzer wearing a bowtie.” Apparently Clark is “terrified” of this interview coming out, so I applaud Madden for releasing it. So her dad spent some time in jail—so what, who cares? You can only spend so much time with this shit before reverting to Joy Behar, the correct attitude to have toward all pop culture ultimately.

Friedman’s report has some points worth going over: “I was surprised to learn she’d been around for about 14 years and never had a hit. Hits are usually the requirement of being a pop star as opposed to a bar act. Then she turned up on Paul McCartney’s McCartney III Imagined, so I thought, oh, well, maybe better think about her… Who the hell is St. Vincent? I don’t know. Her name sounds like a hospital.” I don’t really know, either, despite following music closely in nearly every year of her project’s existence. I’ve listened to several, I think, St. Vincent albums, and I remember liking the one with the red cover and the song about pills. That’s a good album.

Masseduction—that’s the one. She strikes me today as somewhat analogous to Linda Perry, but again, no hits. I wrote this article two years ago defending Clark against a “histrionic” journalist upset by the artist’s brusque and even rude attitude. “The last thing a journalist should be concerned with is whether or not their subjects like them, and when Young recalls trying to butt into a conversation Clark was having with others at an art opening, Clark’s brusque dismissals become easier to understand. If you’re an awkward, sensitive person, profiling celebrities is the last thing you should be doing.”

Still true, but I must be honest and point out my defense of Clark’s aloof behavior: “She’s a rock star.” Well, no, she isn’t, because she doesn’t have a single fucking song that anyone will know or remember in 30 or 40 years. The Buggles do. So far, Clark has come up short. She’s playing the part of the rock star, putting on the full promo push show—the notion of an album having a “story,” and interview as performance art. When, as it turns out, Clark has made more of a story for herself than her album with this call to kill a working journalist’s story because of post-interview anxiety.

But she’s still the province, it seems, of music journalists and people already in the industry. Friedman: “Madden says she next heard from someone at Clark’s PR team (she has a PR team–I’d never heard of this woman until recently)–who told her the interview had been “too aggressive.” Uh huh. I’m trying to imagine Madden holding a gun to Clark’s head.” The issue isn’t just magazines and websites’ reluctance to play hardball with artists, but the possibility of ever changing the current reality, the way it’s always been in entertainment journalism.

Because the “precedent” that Alicia Lutes is worried about being set was set a long time ago, and access is entertainment journalism—what else is there? How could you justify digging through the garbage of a celebrity, or hacking their phone, or following their every move? Again, a dotted history: let’s not forget how News of the World and Princess Diana met their ends 15 years apart. TMZ and other aggressive paparazzi also cooled down in the early-2010s, and we won’t see another “LEAVE BRITNEY ALONE!” moment for some time. Why bother? Who wants to drive another young person into early insanity a la Lindsay Lohan or Amanda Bynes? Did the entertainment press really have anything to “uncover” when Rita Hayworth’s mental health started deteriorating in public?

Lutes is right that entertainment and the entertainment press effect our culture, and there are lies and fictions in all of it, since the turn of the 20th century. So in the spirit of Hopper, Parsons, and Kilgallen, I’d like to know what the “white collar crime” was. Probably something boring, but maybe there was more than money and Swiss accounts involved—read Madden’s interview to find out.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith