This is how my mother described it:

My grandmother refused the feeding tube that would have prolonged her life. She could not speak or swallow. She could not walk, or move, nor support her own weight. With my mom, dad and grandfather in attendance, the hospice worker who had come to the house administered a dose of liquid morphine to ease my grandmother’s pain, slow her respirations and lead her out of this life and into whatever it is that follows. And then the rain came—sudden and thunderous, with a sweeping darkness that covered the costal Florida city where my grandparents lived. The hearse from the funeral home arrived and two men came up to the apartment to collect my grandmother’s body, looking—and my Italian mother laughed about this part—like they’d just stepped off the set of The Sopranos. They loaded her into the hearse still sitting in her wheelchair because her body was too contracted and rigid to straighten out.

It was April 27, 2000—the day my grandmother died of ALS, more commonly referred to as Lou Gehrig’s Disease.

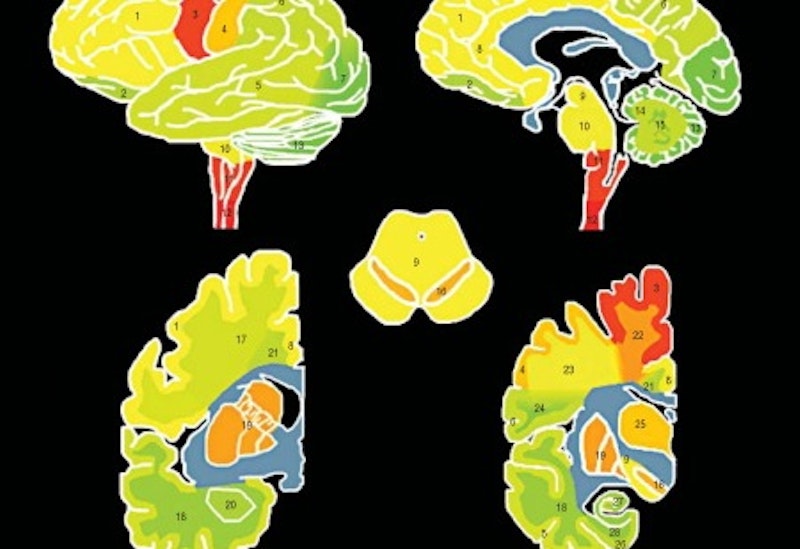

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that targets the body’s motor neurons—the nerves responsible for voluntary muscle movement. As the motor neurons degenerate and eventually die, the brain can no longer send signals to initiate and control muscle movement. Over time, the muscles weaken and atrophy from lack of use and as the disease progresses through the body, ALS sufferers become increasingly paralyzed.

It’s not the sort of disease that is obvious at the onset. The initial symptoms can be quite varied, but usually include muscle stiffness or weakness in the hands, arms, legs or the muscles used in speech. For my grandmother, it was her speech that went first. She began slurring her words and having difficulty swallowing—signs that at first led doctors to believe she’d had a stroke. It wasn’t until several months later that she was finally diagnosed: ALS, bulbar onset. It’s a form that affects the throat and speech muscles first, more common in women over 50 and a faster track to early death than other forms of ALS because it affects the respiratory tract far sooner. My grandmother was 65 at the time of her diagnosis.

I remember visiting my grandparents shortly after and feeling shocked by the disease’s effects. She seemed healthy enough, perfectly mobile and with as much energy as I ever remembered, but she had to constantly hold a Kleenex to her mouth, pressed tightly against her lips to catch the ceaseless trail of drool that leaked out. The disease was forcing her body to create more saliva, while also hindering her ability to swallow it. She couldn’t speak, but wrote everything down on a little note pad. “That was a good hand,” she’d scribble in her shaky handwriting while we played poker at the kitchen table. We used cookies for poker chips—it’s one of the things I remember most clearly from my family’s infrequent visits to our grandparents’ house. Someone would make a quick joke after winning a hand and it would send my grandmother into hysterics. She would laugh and laugh, to the point where she struggled to catch her breath and her entire body shook from the impact of her laughter. When it was time for us to leave, she’d start crying. A few tears quickly turned into full body sobs and the saliva would build up in her mouth, spilling over the edge of her lips and threatening to choke her. ALS makes it more difficult to control your moods.

Her legs went next, progressively weakening with time. It became increasingly difficult for her to walk up and down stairs and the danger of falling led to her scooting down the stairs on her butt with my grandfather moving along behind her, holding her body steady. Eventually, her legs became fully paralyzed and she was confined to a wheelchair. My grandfather would have to lift her from the chair to the bed and vice versa. Her life became one of full-on physical dependency.

In the two years after her diagnosis, my grandmother deteriorated dramatically. She became smaller and smaller, her body shriveling up and contracting toward her center. Her ability to communicate by writing notes disappeared as the disease affected the muscles of her arms. She would slowly tap the computer keyboard with her fingertips to send us emails about how she was doing, what she was reading, and the cards she was playing via her WebTV programs. Over time, the emails grew shorter. “Feel ok,” or “How kids” were all she could manage because she only had use of one finger. Eventually, her fingers lost movement entirely and she needed an extension attached to her wrist so that she could continue using the computer at all.

For as long as she could manage, my grandmother kept busy by using WebTV. She researched her disease and interacted with other ALS patients online. As her body slowly wasted away, her mind achieved a level of clarity that people seem to only gain as their lives approach their end. She was 67 when she died, two and a half years after her diagnosis.

There is no cure for ALS. While there are drugs that slow the progression of the disease, there is no treatment that can reverse its effects. Research into the etiology of ALS has increasingly uncovered a hereditary link, but the cause of the disease remains largely a mystery. I often worry that the genetic link exists in my family and my mother will be diagnosed with ALS. And if not, perhaps it skips a generation—like twins—and my brother, sister or I will suffer from it.

ALS is a quiet disease. You don’t hear about very often in the news. There’s no celebrity leader to act as the face of ALS—Lou Gehrig died in 1941; Stephen Hawking’s struggle with the disease is an uncommon one, having already lasted for more than 10 years. May 1 marks the beginning of National ALS Awareness Month. I’m not imploring anyone to donate money or volunteer. But please just take a moment to stop and think about this disease, about all the people who have died from it and all of those living with it today. A moment for all those people who threw their cookies onto the pile and got dealt a crappy hand.

The Quiet Epidemic

On the eve of National ALS Awareness Month, a personal look at the effects of this degenerative disease.