Everyone always has such awful things to say about 80s fashion. Most folks look back on the decade and say, “What the hell were they thinking? Shoulder pads. Oversized sweaters. Big, teased out hair. Polka dots. Headbands. Stonewashed jeans. Overalls. Neon everything. WTF!” But whether you like it or not, these trends are definitely back. Likewise, there couldn’t be a better time for the hip New York art gallery Deitch Projects and luxury behemoth Louis Vuitton to collaborate on a new retrospective installation highlighting the legendary punk rock fashion designer Stephen Sprouse.

Stephen Sprouse (1953-2004) was an influential 1980s fashion designer who, even before Dior Homme’s Hedi Slimane, a legend in my eyes, fused rock ‘n’ roll into fashion and art. Inspired by street culture, graffiti and especially Day-Glo colors, he rolled with some of the hottest downtown scenesters, including Keith Haring and Andy Warhol. And known largely for an all black palette punctuated by electrifying neon colors and avant-garde shapes, Sprouse’s garments feel like works of pop art. They’re not unrelated, for example, to the artist Peter Halley’s own Day-Glo canvasses of the same time period.

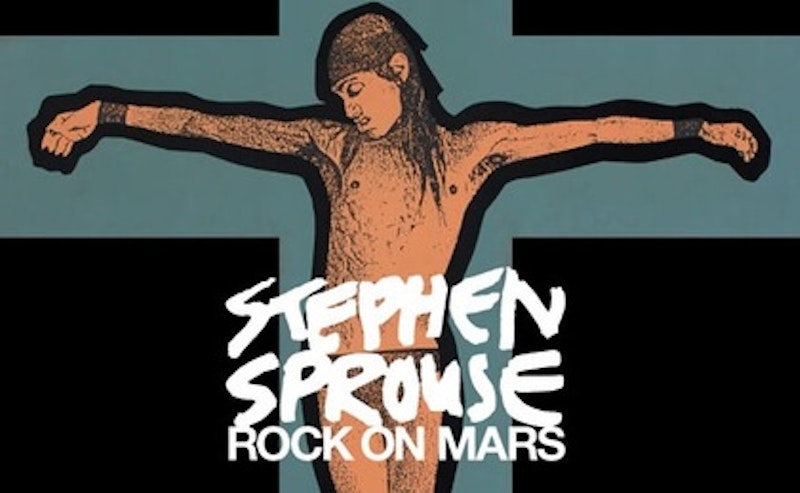

Rock on Mars, on view at Deitch Projects until February 28th, is a nostalgic proto-runway show about the collaborative spirit of the 1980s art world. You won’t find boring, amateur landscape paintings here. The walls of the gallery, which are usually blindingly white, have been painted a metallic silver color. On the balcony level, you can see taped footage of a Sprouse fashion show from the 80s. At the basement level of the gallery, a black light emphasizes the neon color palette in Sprouse’s design sketches. Finally, large paintings of boomboxes, screenprinted in Day Glo oranges and greens, set the tone for the entire space, showcasing the relationship between music, fashion and the street. You’re completely surrounded by dozens of mannequins dressed in Sprouse’s neon pieces. And while the models are stationary and raised just above you, when you move through the gallery, inspecting each outfit one by one, there is the sense that they are moving along with you, too; that they’re not stationary but very much alive, thanks to all the bright colors.

One of my favorite pieces in the exhibition is a male model dressed all in black and a long, electric orange fur coat. Fierce! Also really hot was this skimpy dress made almost entirely out of safety pins. Trust me, it’s hot. As is true with any runway fashion, the clothes are impractical. They’re so bright and ironic that it feels like you’re at a hipster dance club. The real irony though is that while the outfits feel incredibly Now, they are historic documents of a moment passed, one for which many of us are incredibly nostalgic.

If you’re thinking that the boundary-crossing world Sprouse created sounds a little something like Andy Warhol’s brand of pop art, you’re right. Sprouse was one of the first people after Warhol who aimed to completely destroy the boundaries between high art, music, fashion, industry and street culture. And that’s what’s so great about art from the 80s: it was colorful, bold, and really interested in bringing people from different artistic communities together. Who had ever heard of neon and graffiti covered clothes as works of art? The best work is work that’s open to other ideas and innovations from outside your comfort zones.

And that’s the real significance of the exhibition, or at least what I take away from it anyway. I don’t think it’s a stretch to suggest that Rock on Mars is timely not just because we’ll never kick the habit of loving 80s fashion, but because it also speaks to a particular cultural, historical moment. When Barry O. took the White House on Tuesday, we were inundated with messages of unity and togetherness. Barry encouraged us to break the boundaries of race and class, gayness or straightness, religion or whatever it is that keeps us from working together. Barry implied, like Sprouse’s interdisciplinary art does, that the most productive, innovative and arresting ideas come only when we learn how not to be intimidated by artificial boundaries.

Stephen Sprouse Still Astounds

The deceased artist is featured in a new exhibition co-sponsored by Louis Vuitton.