Many strange wonders were hidden within the seventh issue of Who’s Who: The Definitive Directory Of The DC Universe, but none more spellbinding than Tony DeZuniga’s illustration of Doctor Thirteen. A blue monochrome background revealed monsters, ghosts, and metaphysical action, unfinished sketch forms dancing around a jaunty scholar clad in brown formal wear and a windbreaker. He smoked a pipe and wore dark-rimmed glasses while reading an arcane scroll. His scruffy brown hair rustled in the breeze. His demeanor was a blend of contemplation and grim resolve. Doctor Thirteen was someone who’d lecture at a prestigious university by day while moonlighting in a profession that demanded excitement and mystery.

Filipino creators like Jesse Santos, Alex Nino, Sonny Trinidad, Ernie Chan, and DeZuniga revolutionized the language of sequential art. They were originators of a pastiche approach in which sensuality, graphic design, and Frazetta-esque realism all mingled fluidly in ways that’d become synonymous with Heavy Metal, 2000 AD, and other experimental adult comics that came out in the late-1970s and 80s. DeZuniga and most of his contemporaries began working in the US roughly 10 years before adult comics peaked in popularity. The industry was then still a niche market for kids, so there were few titles that made an easy fit for the bold new works. Despite that, these artists held on to their aesthetic identity without mangling the tried-and-true conventions beloved by mainstream publishers of the pre-Heavy Metal era.

DeZuniga’s scratchy poetic style blossomed in some of the more offbeat DC publications: Phantom Stranger (a series that mixed the horror and superhero genres; in addition to its immortal Shadow-like title character, it co-starred Doctor Thirteen, a para-psychologist and eternal skeptic obsessed with uncovering supernatural charlatans), Adventure Comics (where he drew stories that starred Black Orchid, a mysterious super heroine with multiple alter egos), and books featuring the Old West gunfighter Jonah Hex. Possessing a severe deformity and a misanthropic chip on his shoulder, Hex and his dust-choked exploits were rendered by a large number of artists from 1971 to 2015. DeZuniga co-created Jonah Hex, so naturally the artist drew the scarred gunslinger’s most compelling appearances in All Star Western, Weird Western Tales, and an eponymous title.

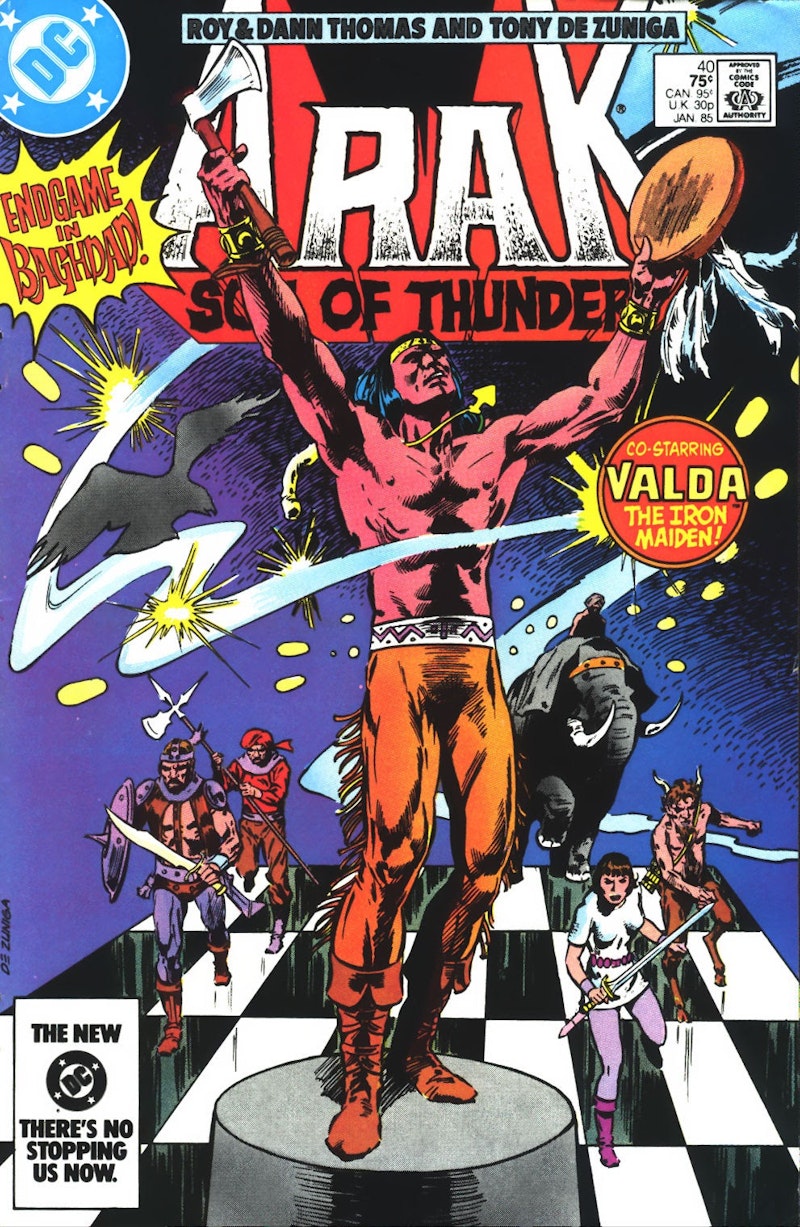

Beginning in the 1980s his resume expanded to include stints working on stories with a variety of characters from the DC comics universe and many from the Marvel pantheon. DeZuniga then plunged into new realms of experimental fantasy with Arak Son Of Thunder, a young Native American warrior-shaman adopted by Vikings after his tribe is massacred by an evil serpent god’s cult. Arak debuted as a back-up feature in DC’s popular title Warlord before getting his own book. Combining disparate strands of historical fiction, mythology, sword and sorcery, epic poetry, and science fiction, the ambitious series was in perfect harmony with the artist’s visionary pastiche.

The original creative nexus for Arak Son Of Thunder included writer Roy Thomas and artist Ernie Colon. DeZuniga inked Colon’s pencils on the first four issues. Different creative teams came and went over the series’ 50 issues with notable turns from Ron Randall, Rick Magyar, and Alfredo Alcala. DeZuniga returned as primary artist with issue 38, and Arak’s greatest run began with no. 44 when Roy Thomas joined forces with his wife Dann to focus on writing plots, and the married co-authors Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier took over scripts.

In scenes with emotionally charged dialogue DeZuniga brandished quiet realism and subtlety. Scenes with bloodthirsty monsters and explosive displays of supernatural power were rendered using abstract shapes and clustered athleticism. Between bursts of action and drama the artist brought out minimalist design elements that symbolized progress, images without detail that shoved realism into the periphery. The narrative never suffered in his hands yet it never controlled his work. Tony DeZuniga depicted continuity’s inertia as the primordial cosmic ooze from which all stories emerge.