What does it mean to watch something ironically? To grasp that, you have to comprehend irony first—and our understanding of irony is still badly corroded by irony’s conceptual proximity to sarcasm, its noisy simpleton cousin. But, as good linguists are sometimes at pains to explain, irony is a nuanced form of misdirection. It’s not, necessarily, that you mean the opposite of what you’re “saying” when you’re being ironic. There’s just a constructive tension between your explicit and implicit meanings. Likewise, when you’re consuming television ironically, there’s a tension between what you, as a viewer, might reasonably expect, and what actually happens on the screen.

This often gets portrayed in an over-simplified way, as laughing at something just because it sucks. But that really is an oversimplification, which is why it’s now often necessary to distinguish between television that’s “so bad it’s good” and television that’s just horrible to watch. Really bad television, you’ll notice, never contradicts your expectations. The heroes are humble and plain-spoken. The villains are resentful masterminds. The drunken, unemployed fathers turn abusive. The mousy office assistant falls in love with the former prom king, and he soon realizes he feels the same way. Everything’s completely foregone: not one hair is out of place, unless you count the deliberately mussed ‘do on the rich kid gone wrong.

Meanwhile, there’s a whole other universe full of shows that deserve your attention. They aren’t cleverly deceptive. On the contrary, they’re astonishingly clumsy. They don’t understand themselves, so they don’t know what expectations they’re supposed to meet, or what they’ve done wrong. Sometimes this is because they were hastily made. Sometimes they’re trying to reach too many audiences simultaneously. There are even a few gawky little monsters that come into this world when passionate, delusional auteurs manage to press-gang a network into backing their magnum opus, and it turns out to be everything except good.

Regardless of its origin story, though, “camp” is consistent in one respect. The fabrications that are supposed to coalesce into a seamless fiction come unglued instead. When they do stumble, you can glimpse the little men and women behind the curtain. I’d say the overall effect is a little like the hilarious scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey where the computer sings “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do…” as its circuits shut down. When this happens, in the movie, the computer (the HAL 9000) is having a grim, life-or-death conversation with the hostile astronaut who’s decommissioning it. Then, out of nowhere, it starts to sing. That means something profound for us. It means there are still cracks in the system. Open up the hood—out comes a vaudeville tune. You can react any way you like. That’s quite a change from the feedback loop of slick programming, at once narcotic and agonizing. Most TV shows us what it thinks we want to see, then gives our feelings a series of hard shoves. But some of it’s corny, laughable shlock that’s too crammed with contradictions to oppress anyone. Stuff so bad that it’s good. There’s a whole asylum’s worth of it out there, too, hiding in plain sight.

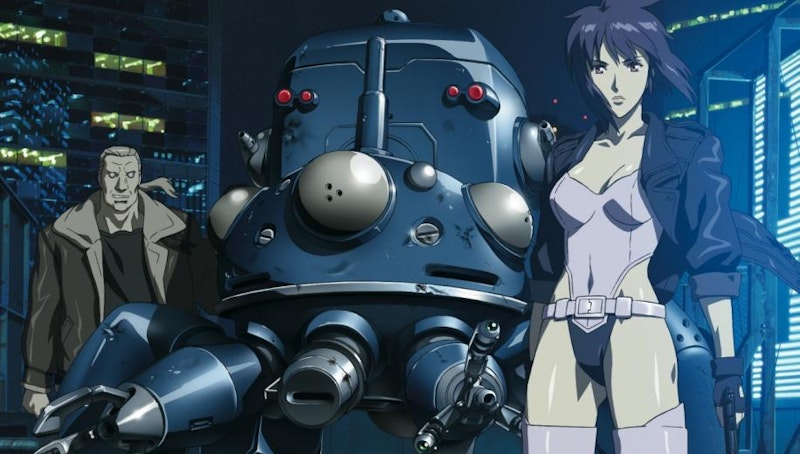

One prime example is the animated series Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex. Written by a “committee” of Japanese manga enthusiasts, the show expands on the world and characters who first became superstars thanks to Mamoru Oshii’s groundbreaking anime Ghost in the Shell. All the show has done, in building upon a foundation Oshii set in place, is ruin everything he achieved with profundity and grace in his film. His film is a tapestry of delicately balanced impulses: cheap thrills, philosophical speculation, noir style. It’s a film about social control that manages to seem ruggedly individualistic. It’s a film about freedom of thought that takes behaviorism as gospel truth. It’s cynical about everything, yet utopian. It has a “girl power” ideology and an unnervingly male gaze.

The show takes all these painstaking aesthetic syntheses and knocks them completely out of whack. It tries to cash in on the “crossover” appeal of the movie (i.e., the fact that Ghost in the Shell did well in America) by including English dubbing, but leaves everything else to the cheap, assembly line studio process that’s standard for all adaptations of mangas in Japan. The result says more about Japanese culture than the original movie ever did. Start with the title, which is as rich a tapestry of pointless interlacing meanings as you’ll ever find outside of a Derrida conference. A “stand alone complex” is an architectural term for a group of buildings that are relatively isolated; here, it means a group of television episodes that can be viewed without watching the movie first. It also refers to a “ghost” (a consciousness) that’s still “alone” because it hasn’t been fully integrated into the global Internet; this is a “complex” (a series) about such lonely ghosts. Finally, it refers to somebody who has a “stand alone complex” in the Freudian sense: that is, a prickly loner, or an outlaw.

Lest you think I’m making some of this up, or reading too much into very little, these meanings are explicated in the opening episode by a short written introduction that flashes onscreen. That’s how seriously the show takes itself. Adding to the general mood of not fooling around is the (first) theme song, which features the Russian singer Origa screaming “Falling, fall-all-iiiiiiing,” in English, while a child (obviously a younger version of the protagonist, Major Kusanagi) tries desperately to grasp a doll. The doll breaks into pieces. So, to quote Airplane!, now we know what we’re dealing with. This is going to be a very intensely psychological show about a protagonist with a troubled past who’s always verging on a nervous breakdown. That’s right, isn’t it? Isn’t it?

Nope. That’s not how the show goes at all. The “Major” is a basically emotionless functionary who does her job coldly and efficiently, without ever worrying too much about the fact that she’s a brain in an artificial body. The overheated theme song and the emo montage accompanying it are simply there because they come standard with this kind of Japanese storytelling. I’m reminded of Kill Bill Volume 2:

Budd: You’re telling me she cut her way through 88 bodyguards before she got to O-Ren?

Bill: Nah, there weren’t really 88 of them. They just called themselves The Crazy 88.

Budd: How come?

Bill: I don’t know. I guess they thought it sounded cool.

That reminds me: why are the lyrics to the theme song in English, Russian, and—ahem—Latin? Well, because the Japanese find that compellingly, refreshingly different. So now you have a Japanese show, appropriating “cool” English words in its theme song, being sold to an American audience eager for “exotic” Japanese anime. The two cultures grasp each other in an endless, mirrored embrace that iterates forever. To feel how strange this really is without seeing it yourself, imagine Friends with a French theme song. (“Yes, folks, here comes the new hit by the Rembrandts, ‘Je serai là pour toi’!”)

If you investigate the history of the theme song, things get even campier. It was written by Yoko Kanno, and it remains one of the primary reasons why she has a Wikipedia entry and you don’t. In an interview about it, Kanno had this to say: “I had this image of a formal and rigid 'manly' world for the original comic. So I tried to think of ways to destroy that world. The theme I had in mind was, 'be human.' It represented the sentiment of 'why don't we take it easy and be more like a human being?'—instead of being a workaholic salaried man working for his company...For the opening theme song called 'inner universe,' I had an image of digital bits and composed a score consisting of recurrent quick beats.”

Why is Kanno trying to “destroy” the “world” of an anime program that’s hired her to write a theme song? Because that’s what she thinks good artists do; she thinks they’re quirky, feminist rebels who destroy the “formal...rigid…’manly’” worlds foisted upon them. Except a theme song can’t destroy anything, and for the most part, her rather delusional theory of what she’s doing leaves no trace. For the most part—but you can tell something’s off when those choruses (“Falling, falling…”) come pulsing through. The nonsense piles up quickly. On top of her appetite for destruction, there’s Kanno’s message (“be human...instead of being a workaholic”) which has nowhere to go in a show about a bunch of secret agent workaholics who aren’t human. This is how a work of art that doesn’t know itself comes lurchingly to life.

There’s another thing worth investigating here. Major Kusanagi (in particular, though the whole cast is the same way) speaks a very peculiar form of baroque English. She adds philosophical asides to everything she says. “Dreams are [only] meaningful when you work towards them in the real world,” she tells one villain. To another, she advises: “If you’ve got a problem with the world, change yourself. If that's a problem, close your eyes, shut your mouth, and live like a hermit.” The show doesn’t stop when she utters these words of wisdom, in order to foreground them; instead, it seemingly ignores them. That’s because they’re bad translations of Japanese sayings; they’re versions of ideas that are second-nature when you’re speaking Japanese, and that can be said in much more condensed ways in that language. Coming from an action hero, they’re as funny as the philosophical speeches Patrick Swayze gives in Road House.

I’m not saying that Ghost in the Shell: SAC is essential viewing. I’ll save that canonical status for the original film. But it is something to savor. It’s a show that comes out of a soulless factory for mass-produced art, yet what’s been created doesn’t feel mass-produced at all. It’s not seamless and smooth like an Apple product or Better Call Saul. It’s glitchy and human. That doll breaking apart doesn’t belong to the Major, as far as we can tell, given what the show reveals about her. But it belonged to some storyboarder, out there, in reality. You can tell as much precisely because it shouldn’t be there. And perhaps that’s the only way that our technicolor dreams become meaningful now: when they break, and reality comes pouring in.