Heavy drinkers call New Year’s Eve amateur night. In the same way, the fight over literally inspires some impatience on the part of Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage, fourth edition. The reading public encounters a politician literally walking a tightrope or a restaurateur who literally empties his wallet. How does Fowler’s describe the resulting fuss? The “screaming abdabs.” The book’s preferred take on literally is rather complex. “Once it is analysed as part of the verbal image and not as external to it, the use makes good linguistic sense,” the guide tells us.

I’ve read that thought and its surrounding paragraph a number of times and they remain opaque. By contrast, Merriam-Webster is clear but wrong. To the approved definition of literally (meaning that a word, phrase, or statement matches physical reality with no equivocation) it adds this: “in effect : VIRTUALLY.” That is, black also means white, exit also means entrance.

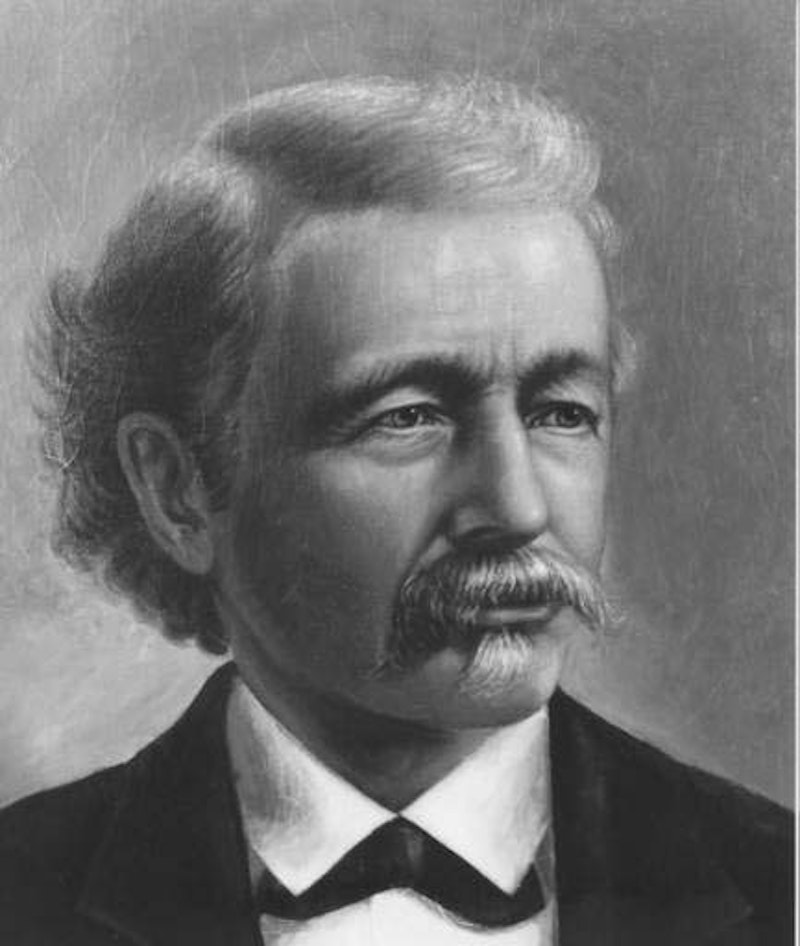

I prefer the thinking of the deceased Henry Bradley, editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, who added this note to the word’s definition in 1903: “Now often improperly used to indicate that some conventional metaphorical or hyperbolical phrase is to be taken in the strongest admissible sense.” The quote occurs about halfway into the Fowler’s entry, as part of a tour through the history of the word. I’ve seen the thought expressed nowhere else. Too bad, because Bradley put his finger on it.

Prince Andrew tells us about his grandfather, King George VI, “who had literally been catapulted onto the throne.” The forceful and vivacious Hoda Katebi, an American activist, asserts, “This country was literally built on the backs of black slaves and after the genocide of indigenous people.” One sees what they mean. No, George wasn’t loaded onto a contraption, and a rope wasn’t then cut so he could hurtle toward his seat of majesty. No, Idaho and New Hampshire and the rest can’t be found resting on the spines of black people held as property, and in fact none of the states were ever located there, not before, during, or after construction of anything within them. But George was made king not just quickly but suddenly, with little time to get used to the idea of being monarch. And America didn’t just get a handy boost from unpaid black labor; the slaves made a crucial contribution to American prosperity, and more often than not this contribution took the form of brutally hard manual labor.

Anyway, these would be the two points made by the prince and the activist. In each case the speaker wants to make clear that a dramatic but familiar phrase is being used with an emphasis on the drama, not the familiarity. The speaker indicates that he or she knows that “catapult” or “built on the backs of” might be used by some careless person to mean a situation that was merely sudden or a contribution that was merely important. The speaker waves us away from such a thought. No, the speaker wants us to know that the phrase has been looked over and is used with its full force in mind. In making this signal, the speaker uses a word with an impressive up-and-down run to its syllables. Wanting to remind us that a phrase should be taken at full weight, the speaker also tickles his or her sense of importance.

There’s not much to approve of here. Choose a phrase that doesn’t need a stamp that says, “I’m not kidding.” Don’t choose words because of how they make your throat feel. But these two strictures will never be met, and in the meantime a word is needed. People will always reach for literally, and short of homicide the rest of us must lump it. We have virtually no choice.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3