This is part of a series of posts rereading comics from my childhood. The last one on Tarzan is here.

Captain America #214

"Power"

Jack Kirby

October 1977

I've had this comic for 40 years, but never knew who wrote it. When I returned to reread it, though, it hit me with enough force to "send me off the Richter Scale!" as Falcon declares.

It's KIRBY THE KING! FZAAKK!

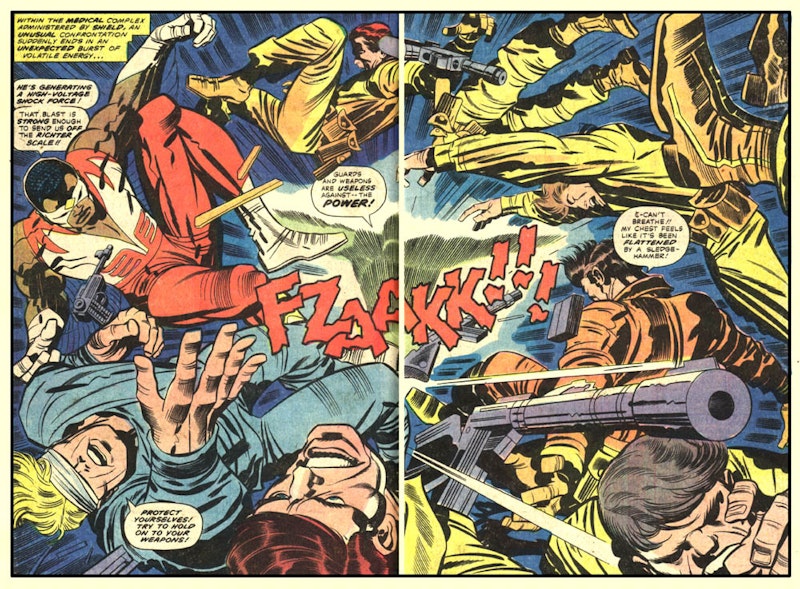

I'm not the world's biggest Kirby fan, but after reading a bunch of mediocre 1970s comics, there's no denying that Kirby is a breath of fresh air, or a breath of pounding energy blasts. The high point of the comic is a Kirby-esque two-page spread in which the nefarious Night Flyer releases "Power!", sending Captain America, Falcon, and a bunch of SHIELD Agents flying around the room. The image is both ridiculous and awesome; the SHIELD Agents blowing outward from the bad guy, their blocky limbs arranged in a kind of blast radius ballet. The gun in the right hand panel is pointed out at the reader, as if it's going to shoot right out of the page. On the left, Captain America, aka Steve Rogers (in the blindfold) flings one of those weird, mightily-knuckled Kirby hands up in a gesture of supplication, while the guy next to him seems to be trying to catch up to his own enormous jaw.

The image is a neat encapsulation of Kirby's themes in the story as well. The comic is called Captain America, but it's not especially focused on the putative hero. Instead, Steve (who is temporarily blinded through most of the comic) and the Falcon are mostly treated as part of an ensemble of semi-anonymous soldiers. The Night Flyer is storming a SHIELD space station in order to assassinate a defector. SHIELD troops, including Cap and Falcon, try to stop him. The story is more about military camaraderie than individual valor. Superhero films today love daring individual mavericks, but Kirby’s comic encourages readers to imagine themselves as binding themselves to a collective purpose.

Kirby's left-of-center fans praises his collectivist impulses as progressive, and in some ways, the comic is quite forward-looking. Black superheroes were still rare in comics in 1977, and Kirby writes Falcon without recourse to stereotype. Luke Cage's white writers often cursed the character with embarrassing quasi-ghetto slang, but there's none of that here. Instead, Kirby gives Falcon a bunch of delightfully corny one-liners. The hero declares that he feels "like a deep sea diver at the bottom of a bowl of tapioca pudding!" or boasts "It'll take only second to put your electric generator through the shredder, Mister Live-Wire!”

Black superheroes were rare in the 1970s; blind heroes are still almost unheard of today. Daredevil, of course, has super senses, so he doesn't really need his eyes. Captain America in this comic, though, has super strength and super reactions, but his inability to see is a major hindrance. Nonetheless, Cap leaps into the fight, and holds his own relying on hearing and his wits. "Whatever happens now can only be a plus as far as I'm concerned! If my functioning faculties remain sharp, I may get some licks in yet!" Nor does anyone reprimand him for doing too much or putting himself in danger. Instead the assumption by both his comrades and his scripter is that Steve is the best judge of his own abilities.

But while Kirby seems up-to-date in some respects, in others the comic feels like a relic—not of the '70s, when it was published, but of the 1940s.

America had withdrawn from Vietnam only four years before this issue came out. But you'd never know it from reading Kirby, whose faith in the virtue and perspicacity of the American military is absolute. As Cap and the Falcon fight the Night Flyer, three interchangeable blocky white guys stare at some patented blocky Kirby machinery and decide that the Night Flyer draws his power from a satellite orbiting the station. The three blocky dudes fire three rockets, destroying the orbiting satellite, and killing the Night Flyer dead in the nick of time to save Cap.

There's an obvious parallel with Hiroshima; the higher-ups save the grunts with a deus ex missile. The Night Flyer's face after the power surge kills him looks like "the surface of the moon" the Falcon exclaims. The characters spend three panels marveling at how disgusting the damage is, though Kirby never shows the corpse to the readers. I remember finding the sequence very strange as a kid—but of course it makes more sense if Kirby is obliquely referencing a devastated Japan.

At the end of the comic, Captain America muses that the defector—who none of them ever saw—was never on board. "I think it was a cover story to obscure his real location!" Cap declares, and then waxes rhapsodic about "the devious design in the far-flung web administered and carefully guarded by that one-eyed stubble-plastered, cigar-smoking Nick Fury!" The Night Flyer murdered a bunch of men on the station; Cap's saying they died for nothing—or for some mysterious goal of misdirection that only the brass is privy to.

If you assume that the brass knows what it's doing, then that's all well and good. Post-Vietnam, you'd think Kirby would have at least a doubt on that score. Despite his occasional sympathy for hippies, though, he doesn't seem to. His Cap has energy and imagination, but it’s oddly congealed. The comic feels frozen in time.