I love the publisher Hard Case Crime. Inspired by the pulp paperbacks of postwar America—books with sexy painted covers and written by tough guys like Mickey Spillane, Laurence Block, Donald E. Westlake—Hard Case Crime is more than nostalgia. It reinvigorates the idea that male passion is good and beautiful. In the age where fights are waged by texting and belching gets one sent to sensitivity training, this is no small thing.

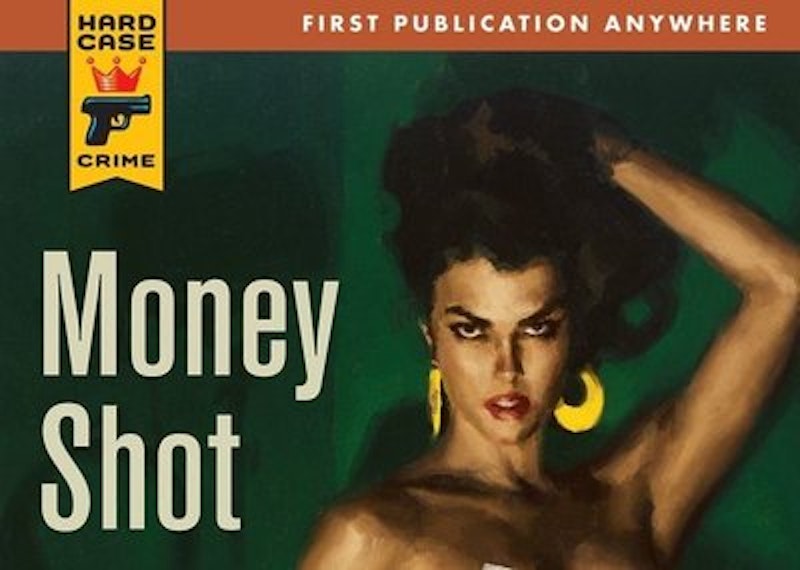

Hard Case publisher Charles Ardai started in 2006 with the intent of self-publishing a few contemporary crime novels whose content and format were inspired by the pulp fiction of the past. What began with a couple titles has now blossomed into a major publishing house, with bestsellers, a TV series based on the hit man character Quarry, and a genuine blockbuster, Stephen King’s Joyland. Hard Case also features gorgeous covers inspired by the golden age of pulp fiction in the mid-20th century. The covers all feature women in various states of undress and in some form of danger. The titles are classic: So Nude, So Dead, Murder is My Business, The Cutie.

Social Justice Warriors would say that this is “damseling”—making a woman a passive damsel in distress who needs rescuing. They ignore that generally speaking women are less violent and more moral than men (look at the prison population), and thus elicit more sympathy from readers when put in dangerous situations. There’s also the pulp tradition of the bête noir, the woman who is sharper and crazier than any man and maneuvers the protagonist to his doom. Of course, then the feminists complain about pop culture always making females characters the enemy.

The simplest explanation for the popularity of Hard Case Crime is that the books, like most pulp fiction and the film noir movies it inspired, are about animus—the Jungian term for male passion. Like a Scorsese film, they depict men on the edge when the world is increasingly hostile to dangerous and flamboyant men. In the 1950s, writers like Jim Thompson and Dashiell Hammett brought readers into a world where carefully manicured lawns, Jell-O and white picket fences hadn’t taken hold. In He Walked by Night, one of my favorite films from the era, the killer literally works underground, sliding into the dark labyrinth of the city’s sewer system to escape detection. Carl Jung wrote about “the shadow,” the part of us that is dark, horny, creative and a bit crazy. In bright and sunny Eisenhower America, crime fiction and film noir were the shadow.

Today’s social justice warriors aren’t comfortable with the shadow. Like the censors of the 1950s, they are forever trying to block, eradicate, change or stamp it out. They’re the people that Vanity Fair’s James Wolcott calls our “hall monitors.” Thus a simple and effective car ad that celebrates a young man’s bravery in the name of love gets described as “rapey.” Hollywood films, from American Beauty to Foxcatcher, neuter men who are passionate leaders in fields of the military or sports. Every sitcom dad seems to be an ineffectual schlub.

In comparison, the criminals, cops, junkies, hit-men and sex-obsessives found in Hard Case Crime seem fully alive. They aren’t liberals, but they also aren’t lad culture conservatives—juveniles like Gavin McInnes, always dropping his pants to get a reaction from the feminists.

Every man who’s fit to live has his own stories about the time, like a Hard Case character, he ducked the police, got in over his head with money, or abandoned himself in pursuit of love or sex. We’ve all climbed up windowsills, driven all night, and gotten into fights over a girl. Of course, a man must be able to read a woman’s signals, and it’s a good thing that feminism is teaching young men that no means no and yes means yes. But there’s also that ambiguous middle ground, where the woman seems interested and indicates, whether verbally or not, that the man needs to prove himself to her. And if that man is any kind of man, he’ll allow himself to feel the awesome power, the wonderful beauty, of uncontrollable male passion.

Hard Case Crime, and pulp fiction in general, is not about controlling and hurting women, although there’s some of that. It’s an expression of authentic male passion, of sweaty sexiness, in a world of pajama boys, government-mandated health food, and reactionary conservative blowhards.