Joanna Connors, a reporter for The Cleveland Plain Dealer, was raped on July 9, 1984. At the time, she was working as a theater critic for the newspaper, and had arrived late to an interview on the Case Western Reserve campus. The production had shut down for the day and the theater was empty. She found herself alone with a man who claimed the theater group would return shortly, offered to show her the lighting system and then, in the quiet emptiness of the Eldred Theater, pressed half of a pair of utility scissors against her throat like a knife, threatened to kill her if she didn’t do as he said, and raped her.

She wrote her story about a month ago in The Plain Dealer; a five-part series detailing the disturbing specifics of her attack, as well as her quest to discover what led a man with the name DAVE tattooed on his arm to intersect her life in such a horrific and traumatizing way. It is a story about learning how to tell her story, about coming to terms with shame and fear, letting go of self-blame and facing the “raw, uncomfortable and sometimes painful truth,” of a day that changed her life forever.

Connors writes: “I’ve struggled with this story for more than 20 years. It scares me so much that I stopped telling it when I no longer had to. I told it to the police, the emergency room nurses and doctor, the detectives, the assistant prosecutor, the judge and the jury. I told it to my husband and my sisters and my mother. And then, of course, I told it to psychiatrists and psychologists, so many over the years I lost count. I told it over and over again, making it shorter, blunter, until it began to feel like I had made it up. And then I stopped.”

I have never been raped. This is one of many things for which I am eternally grateful. I have taken a number of courses that discussed the psychology of victimhood though, read many books about rape survivors and even talked to friends who have been raped. And I am struck time and again, as I was when reading Connors’ story, how significant a role language plays in understanding and conceptualizing this kind of trauma. Rape is not a pretty word. It is harsh and cruel and, as a woman, fills you with an instinctive fear when uttered. Rape is something that happens to you, something someone else us does to your body. But it is also, somehow, something that women are responsible for. We are constantly reminded of how we can prevent rape—carry mace, never walk alone, don’t stop to help strangers, never appear lost, and always check the back seat before entering your car alone. These are good tips, life saving even; but the truth is, no matter how cautious you are, you can still get raped, and then, like Connors, you’re left to feel like it’s your fault.

“I blamed myself,” Connors writes. “I chastised myself for being late, for being stupid: Anyone else would have seen the guy in the lobby and left right away.” She recounts her moment of suspicion, as the man, pointing to lights, made some obtuse comment, something nonsensical and unrelated to theater. She had tried to leave, told him she would just wait outside, but by that point it was too late. She had made a mistake, ignored the detailed rules of rape prevention, and he capitalized on it.

This dual identity—as both victim and responsible party—is partly what makes rape such a complicated issue, such a difficult story to tell. The combination of shame, fear and self-disgust is a paralyzing one and many women choose to live in silence, to keep their stories hidden and untold. But as Connors explains, burying the story doesn’t mean it dies. “It was still alive,” she writes of her own buried rape, “and it grew in that deep place I put it, like a vine from some mutant seed, all twisted and ugly. And as it grew, it strangled a lot of other stuff in me that should have been growing. It killed my trust, my confidence. It almost killed my sense of who I was.”

In reading Connors’ story, it is easy to see that moving past rape and on with one’s life is an immensely complicated process, one that requires learning how to talk about it and taking ownership of the words that describe the experience, the words that tell the story. The language of the experience, the description of the crime, can be instrumental to recovery. Hiding from the word solves nothing, but speaking it aloud requires the type of courage that I am thankful to have never needed.

So imagine what it must be like for Tory Bowen, a woman who, in 2004 at the age of 21, met a man at a Nebraska bar, shared a few drinks and awoke the next morning with no recollection of the night’s events (she alleges that she was incapacitated by a date rape drug) to find herself naked with the man on top of her, raping her. She cannot, however, describe what happened to her as rape, at least not according to the judge that is presiding over her case. Nor can she or the prosecutors use the term sexual assault, or refer to herself as a victim, or the man who raped her as an assailant. Even the words sexual assault kit—which consists of items used by medical personnel to obtain and preserve physical evidence of a sexual assault—have been forbidden. She is left then to describe her experience in the same manner as the defendant: as sexual intercourse, nonconsensual by her assertion, though to me this feels like a moot point, as one must first be awake before they can be expected to consent.

The judge’s ruling is not without some merit. Rape is a charged word. I can understand why he might believe a jury would be swayed by the use of this word, why such a word would convey a harsher, more serious crime than the word intercourse ever could. But rape is a charged word for a reason: because it is an act of aggression and domination toward another human being. Intercourse and rape are not synonymous. A victim should be entitled to describe her assault as she sees fit; the defense can challenge her description during cross-examination. Or even more importantly, if certain words are going to be barred from a rape trial, then the jury should be notified of the barring. But in this case, they were not. Bowen is thus forced to describe her experience in front of a courtroom of strangers in words that are not her own, but that will be taken as such. She must come to terms with her identity as a victim of rape, her own failure to prevent the rape from occurring and now her inability to tell her story in her own words.

This case differs greatly from that of Joanna Connors. It is less terrifyingly violent and aggressive, less frightening for an outside observer. But it is no less a violation of a woman in a situation where she was vulnerable and powerless. It carries with it the same difficulties of coming to terms with a harrowing experience and the need to move beyond blaming oneself and finding the ability to tell the story.

What particularly worries me about Tory Bowen’s case is that, like with all court rulings, this judge’s decision sets a precedent that can be used in future rape trials. Perhaps with this case you can argue that the line between rape and consensual sex is a bit blurry—Bowen recalls so little of the night and there are no witnesses to testify that she was indeed given a drug to incapacitate her. But what about other cases to come? What of those that fall somewhere on the spectrum between Tory Bowen and a young Columbia University student who, in 2007, was raped and tortured for 19 straight hours before being left for dead when her assailant tied her to a futon and set her apartment on fire? How will women be allowed to describe those cases that lie somewhere between incidents that we are unwilling to recognize as rape and those that stand as the most egregious and horrific examples of this crime?

Five Foot Three

How can you describe rape without using the word? A Nebraska court is forcing a young woman to find out.

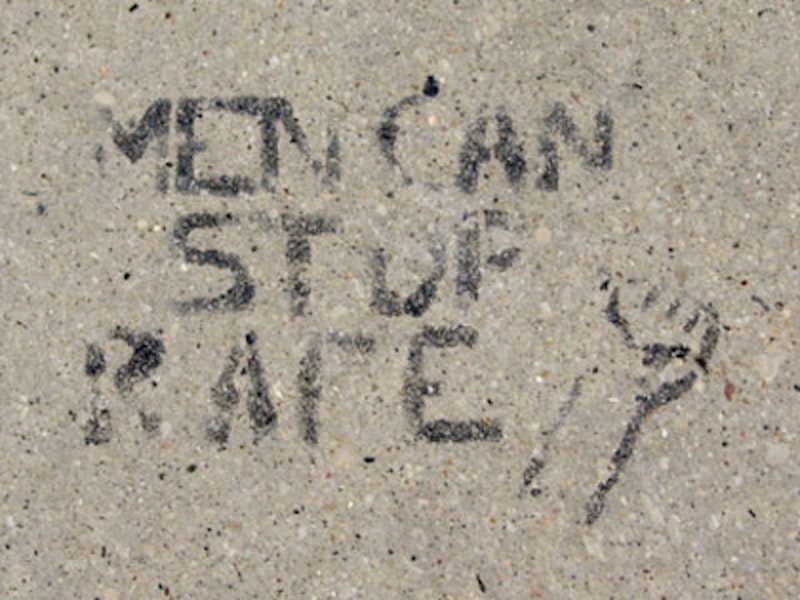

Photo by david drexler