While the early 1980s found DC and Charlton working hard to support fan artists and other outsiders, their biggest competitor kept amateurs at a distance. Marvel Comics never gave amateur art any space in their widely published books. They did collaborate with fans, but none of those collaborations could compare to "Dial H For Hero" or Charlton Bullseye. Marvel Fanfare was a direct sale-only title that debuted in 1982 in response to what the publisher called a “more distinguishing audience.” It was a showcase title where each issue featured the various different characters and pro-creative teams who (up to that point) had gotten the biggest fan mail response from readers.

The 1984 Marvel Assistant Editor’s month event, The Official Marvel Comics Try-Out Book, and the company’s text-heavy fanzine Marvel Age also represented attempts to connect more with fans. Marvel Age was a descendant of their earlier fanzines Marvelmania and FOOM. Both received limited distribution and were related to the earlier Merry Marvel Messenger newsletter that the company published and distributed only for fan club members. The Summer 1973 issue of FOOM featured a portfolio section of fan art submissions, but no stories or full-length features created by fans. The Autumn 1973 edition revealed the results of a contest where an original amateur character creation was to be awarded an appearance in a Marvel comic story. The company didn’t live up to their promise until almost 30 years later when the winning entry (Pittsburgh artist Michael A. Barreiro’s supervillain Humus Sapiens) made it into a 2001 issue of Thunderbolts.

Such lackluster treatment led outsiders to take matters into their own hands. From the 1950s through the 1970s DIY comic book fanzines enjoyed a renaissance. That world was then a nexus for visionaries who couldn’t break through the wall of professional exclusivity that surrounded the comic industry before the direct market’s emergence. The big aesthetic difference between early fanzines and the 1980s mass-produced amateur comics came from three key elements: social dynamics, cultural context, and the fact that most early zine creators worked as their own editors.

During the early Cold War era, comics weren’t taken seriously by the mainstream. Comic collecting, comic conventions, cosplay, and journalism covering the comic book industry were esoteric interests. Nonetheless, the fine art world of the 1960s recognized the power of sequential art. Seminal works by Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and other pop artists, and successful films and TV shows like ABC’s Batman and Mario Bava’s Danger: Diabolik immortalized that new awareness. The façade of snobbish indifference that only gave comics a niche audience was falling apart. Outside of the Pop Art movement and a handful of mainstream media outlets, the first major cracks were formed by the mimeographed/ditto-printed outbursts of the comic mega-fan fringe.

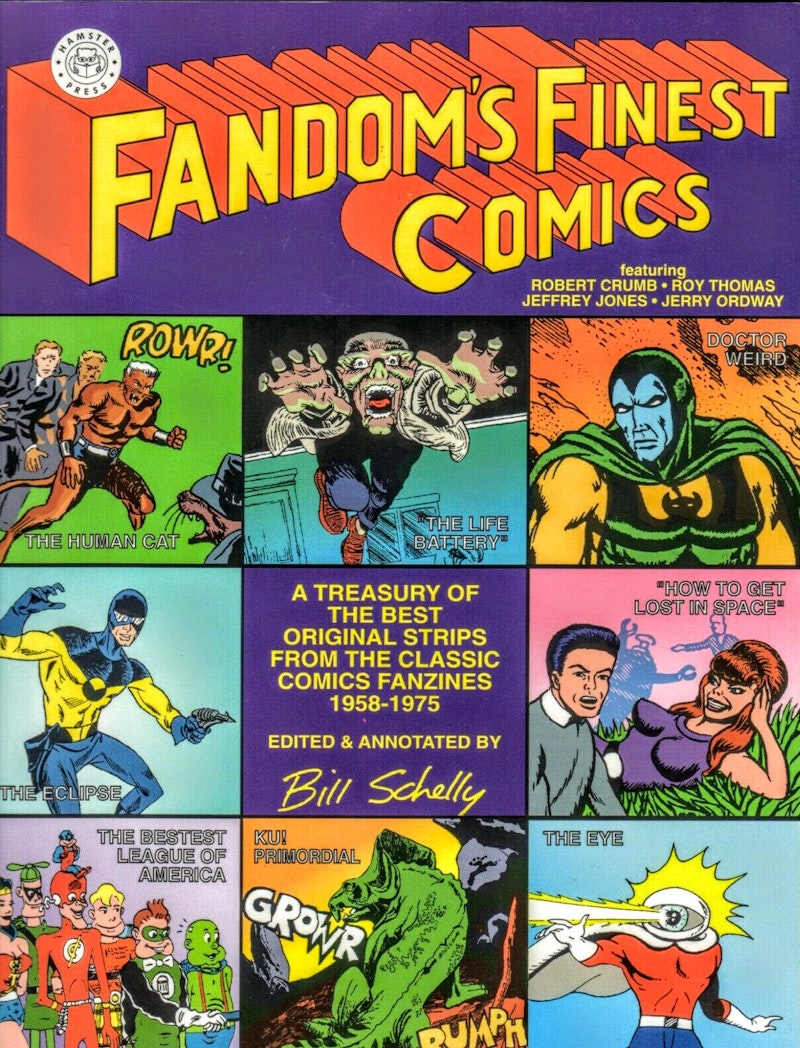

Charlton Bullseye and “Dial H For Hero” reflected the influence of a unified fan community while earlier fan art formed a window into a murky corner of society. A sense of isolation and a skewed philosophy defined this work. Reading pre-1980s fanzines you get the sense that their creators had trouble believing that anyone might care about them. These books were riddled with misspellings, errors in grammar and continuity, smudged ink, and inept attempts at visual realism, which also symbolized the creators’ inexperience and lack of editorial supervision. Early fanzines were usually printed at cost by creators themselves using money from utilitarian day jobs. They were published in tiny editions that received little to no formal distribution. Any larger community of fans and small press entities who supported the early zines existed often only through mail correspondence. Thanks to those arcane origins, their cultural impact wouldn’t gain serious acknowledgment until the 1997 publication of Hamster Press’ Fandom’s Finest Comics. Assembled and annotated by fanzine expert Bill Schelly, this paperback reprint anthology series is the comic book equivalent of a missing link.