Halliburton’s Army, by Pratap Chatterjee, powerfully illustrates the ills of unfettered capitalism. The story of Halliburton encapsulates every disgusting element of corporate greed and corruption, from defrauding the government, to accruing massive subsidies while stealing billions of tax dollars, forging deals with rogue regimes, committing rape and murder with impunity, punishing whistleblowers, pillaging the planet, encouraging imperial wars, poisoning our troops and exploiting cheap labor. What follows are some of the highlights.

As of 2009, the Halliburton/KBR contract was “projected to reach $150 billion” with accrued revenues exceeding $30 billion, according to Chatterjee. The company received “a fee and profit from virtually everything done in the Iraq oil fields” (89) and in 2007 relocated to the “no-tax jurisdiction of Dubai” (211). For those in management this has been a great deal. When President George W. Bush issued an executive order in 2003 to seize all Iraqi assets, transfer them to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York and, via UN Security Council Resolution 1483, establish the Developing Fund for Iraq (DFI) totaling $19.6 billion to “meet the humanitarian needs of the Iraqi people,” Halliburton/KBR was the largest recipient, obtaining $1.66 billion, “primarily to cover the cost of importing fuel from Kuwait,” (104) Chatterjee explains.

In Kuwait, “Halliburton/KBR staff was living at the taxpayer expense in posh waterfront hotels and travelling in expensive SUVs. The Tiger Team was also housed in the five-star Kempinski Hotel for $10,000 per employee, per month” (125). Overall estimates project that “the cost of supporting Halliburton/KBR managers in Kuwait City was an eye-popping $73 million a year,” according to company auditor turned whistleblower Marie de Young.

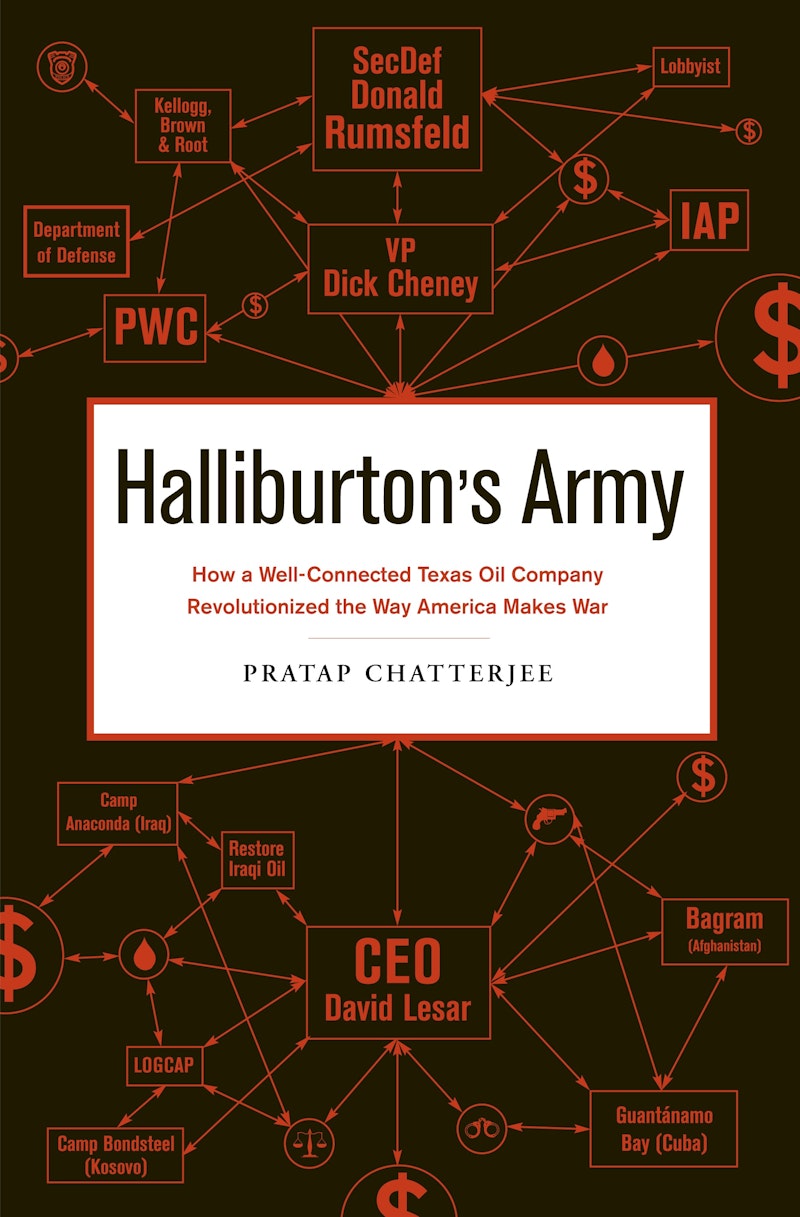

Halliburton obtained no-bid contracts that were guaranteed by Dick Cheney, who ran Halliburton from 1995 till 2000 and received millions in stock options and deferred payments as vice president (which he deposited into his own charity) and further cemented by Cheney’s former boss and longtime partner Donald Rumsfeld at the Pentagon. The terms of these LOGCAPS, as they are called, are also “cost-plus,” meaning that “Halliburton/KBR would submit bills for all expenses, and the government would pay every penny back plus guaranteed profits ranging from 2 to 7 percent,” (83).

The consequences of this paradigm have been devastating for taxpayers. For example, Halliburton signed a contract with a company called La Nouvelle in which the latter “had been tasked to deliver 37,200 cases of soda at $1.50 a case, but delivered only 37,200 cans, resulting in charges that were six times the normal wholesale cost for the drinks,” which, coupled with a similar laundry service scheme, overcharged the government by “more than $1 million per month” (125). Another deal between the two companies for fuel trucks charged “500 percent inflation on the actual cost” (126).

Considering such astonishing corruption it is no surprise that Halliburton has forged many deals with rogue governments. When Cheney was CEO he successfully lobbied Congress to lift sanctions on Heydar Aliyev—dictator of Azerbaijan, who oversaw a campaign of ethnic cleansing aimed at the country’s Armenian population—to secure access to oil in the Caspian Sea. This pattern extends to bribing officials in Nigeria and Somalia and setting up offshore accounts in the Cayman Islands to do business with Iran until 2007.

Those who tried to stop the abuse were punished. The aforementioned Marie de Young explained that when she compiled paperwork about the La Nouvelle contracts “within twenty-four hours, I was told I was off the La Nouvelle account” (126). She added that “the Halliburton culture is one of intimidation and fear […] employees get moved around when they get too close to the truth […] those who tolerated bad practices were promoted” (126). Similarly, Bunnatine Greenhouse, who authorized various contracts for Halliburton, sent the army a 12-page letter exposing ethical misconduct and was eventually demoted: “they stuck me in a little cubicle down the hall, took my building pass […] it’s all about humiliation” (91). Worse, the Pentagon regularly dismissed her admonitions. (Not surprisingly, when she went public with her revelations the Republicans called her testimony pro-Democratic propaganda.)

As is generally the case in U.S. foreign policy, the “unpeople,” to borrow a term used by Noam Chomsky and Mark Curtis, have no voice (unless they happen to demand it through disobedience). When Bush and co. decided how to allocate Iraq’s DFI funds, Iraqi officials were not consulted about whether to award $1.6 billion to Halliburton. Mohammed Aboush, director general in the oil ministry at the time, said he and his advisers wanted to avoid working with Halliburton, which they knew to be inadequate, but, as he put it, “I am old enough to know the Americans and their interests, and they are not always the same interests as the Iraqi interests” (104).

Most despicable, however, is the way in which Halliburton treats its workers—those who comprise the bulk of the company’s 50,000-person army. They often recruit cheap laborers with deceitful job offers. For example, they promised dozens of Indian men from Punjab “$750 a month to work as drivers in Kuwait” (146). These poor souls “each paid $2,700, typically borrowed from a loan shark whom they thought they could pay off in a matter of months” to pursue what appeared to be a dream job. Tragically, they were instead flown to Iraq, had their passports confiscated by management, and, in their words, “were locked up in a small area, which had heavy wiring all around. We were made to do menial tasks for U.S. soldiers like picking up their excreta, washing their clothes, picking up their cigarette butts—all this for US $50 a month, and a plate of boiled rice once a day. If we raised our voice, we were tortured [they eventually escaped with help from sympathetic witnesses]” (147).

Like many others, these victims “were made to drive trucks right into the areas where bombs were being dropped” (147). Chatterjee explains that, “few received proper workplace safety equipment or adequate protection from incoming mortars and rockets” (152). Let’s bear in mind that “70 percent of the company’s convoys are attacked by insurgents” (177). Many have been killed, some taken hostage. Most were made to sleep in tents and flimsy trailers outside the grand bases where U.S. soldiers were housed. “Some were wearing sandals, walking in the mud when it was winter and forty degrees,” and “one guy didn’t even have a coat” (152) according to a witness. Of course they didn’t get sick pay. And, as one worker explained, “we ate when the Americans had leftovers from their meals. If not, we didn’t eat at all” (147).

As for our troops, they have experienced an unprecedented form of warfare. With the war effort now privatized, to the point that there is at least one mercenary contractor for every U.S. soldier on the battlefield, many are stationed in military bases the likes of which have never before been seen—vast, mall-like complexes. In the words of one civilian working on a base, “I live a higher lifestyle here on a base in Iraq than [I would] in the United States. We have free laundry, apartmentlike housing with unlimited, free A/C and electricity, hot water, various American fast food outlets, lounges, free internet, coffee shops, and a large PX that sells thousands of CDs, DVDs, vacuum cleaners, junk food” (11).

In theory this sounds great, since those who are willing to die for America should be treated extremely well. But the truth is far more sinister. First, this is largely a ploy to recruit people to join a dangerously overstretched military. As PR man Tim Horton explains, “what we have today is an all-volunteer army, unlike in a conscription army when they had to be here. In the old army, the standard of living was low, the pay scale was dismal […] But today we have to appeal, we have to recruit, just like any corporation, we have to recruit off the street. And once we get them to come in, it behooves us to give them a reason to stay in” (10). If we had a draft, in other words, it would’ve been much more difficult for the Bush administration to sell the public on “spreading freedom and democracy” in Iraq. Presumably, if everyone were forced to participate there would have been a couple hundred in attendance at Saturday’s White House protests of the occupations.

Furthermore, beneath this seductive veneer of comfort lies an unforgivable evil—much of the food given to our troops is spoiled. According to whistleblower Rory Mayberry, “food items were being brought into the base that were outdated or expired as much as a year” (187). Oftentimes, there was not enough space for food shipments in Halliburton’s refrigerators and freezers at warehouses in Kuwait; according to Mayberry “trucks that were hit by convoys, firings, and bombings—we were told to go into the trucks and remove the food items and use them after removing the bullets and any shrapnel from the bad food” (187); and sometimes “food would stay in the refrigeration and freezing trucks until they ran out of fuel. KBR wouldn’t refuel the trucks, so the food would spoil.” Furthermore, a 2003 Pentagon report found “blood all over the floor,” “dirty pans,” “dirty grills,” and “rotting meats […] and vegetables” (188) in four military messes.

Similarly, in many instances the water at these bases is poisonous. Ben Carter, hired as an acting foreman by Halliburton, testified that at his base, Ar Ramadi, “the water was not being chlorinated” (190). Dr. Jeffrey Griffiths testified that the troops would have been better off drinking “sewer water,” or “water taken directly out of the Euphrates River” (191). At least two soldiers have been electrocuted to death while showering. All this was caused by a “lack of proper tools and materials” (192) that presumably would have hurt Halliburton’s bottom line. Licensed electrician Jeffrey Bliss claims that “carelessness and disregard for quality work at KBR was pervasive” (193). There have apparently been no repercussions, as in the case of female employees such as Jamie Lee Jones and Dawn Lemon who were drugged and raped by co-workers, and then mercilessly denied justice and dignity.

One of the most telling moments of Halliburton’s Army is when the author describes asking soldiers at various military bases he visited “if they were worried about the low wages and lack of human rights for workers. The answer was almost always a shrug” (220). Like most Americans, our troops are generally not heartless monsters. They simply don’t know how the people who serve their food and clean their clothes are being treated. Equally ominous, they’re largely unaware of the harmful effects of corporate food, much like most Americans who, as George Carlin once put it, “are fatally addicted to the slow death of fast food.”

But it’s largely because of companies like Halliburton that the war machine continues to churn with no end in sight. As a prior supporter of the Afghanistan war it now seems clear to me that we’re not fighting to secure ourselves from terror or to spread democracy (how could we hope to achieve something abroad that we arguably cannot attain at home?). We are there to serve corporations and state planners who thrive on mass suffering, indifferent to the soldiers who will die and be stricken with unspeakable injuries, civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan who will be slaughtered and driven from their homes and Americans who will pay dearly with their tax dollars, only to be told that they must now forfeit whatever shreds of the safety net remain “to balance the budget” so that we can continue to wage imperial wars and steal resources from other countries. Only an informed and motivated population determined to resist power can demand change and prevent further destruction.