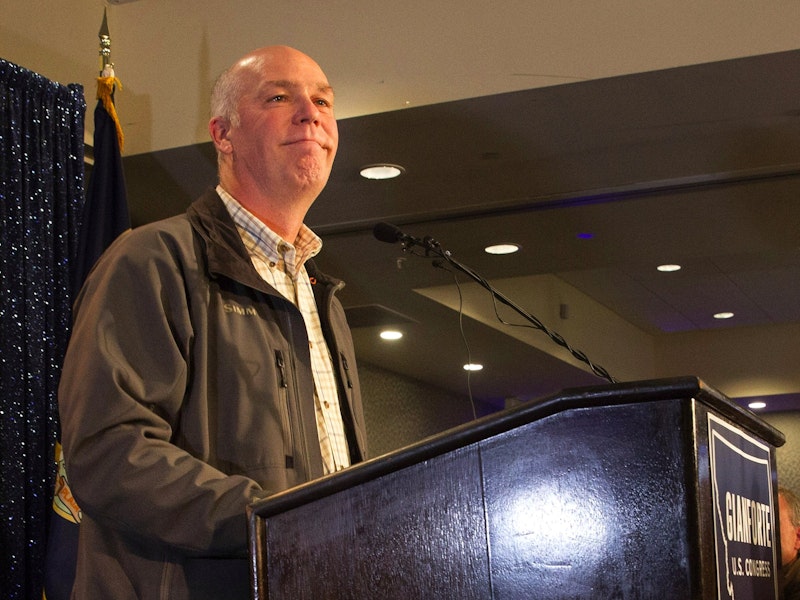

Anyone who wants to be honest about Ben Jacobs, the reporter who was allegedly body-slammed by Greg Gianforte, the Montana Republican House candidate, needs to hold two ideas simultaneously in their head.

The first is that it’s wrong and dangerous to physically assault a reporter. This is a foundation truth of a democracy and human decency. Journalists provide a vital fact-finding service and should feel safe to do their jobs.

The second is that a lot of people felt a frisson of pleasure that a member of the media was beaten down. I think that the reason for that glee, or at least the most understandable reason, is not right-wing bloodlust. It’s that many people have personal experiences of journalists misrepresenting them and even ruining their lives. Whenever there’s an inner-city riot, or a woman cuts off the penis of an abusive husband, liberals mildly denounce the violence then quickly shift to viewing the episode as a “teachable moment” about some larger social problem. The Gianforte episode may provide a similar opportunity for learning a larger truth.

Ben Jacobs was an innocent person simply doing his job. Yet, and this is not rational as applied to Jacobs, it seems possible that a lot of people who’ve been victimized by journalists are using him as a stand-in for their frustrations. Again, this is not fair to Jacobs, and it’s not an excuse for the violence. I’m simply trying to understand what is going on in the heads of those who are defending Gianforte. Jacobs may have become a scapegoat, but he’s a scapegoat for some troubling journalistic malpractice that we ought to address.

I’ve occasionally written about an episode from a few years ago when I discovered that a prominent editor, now ensconced at The Washington Post, was making stuff up and altering the copy of his reporters. The motive seemed to be simple humiliation and malice. In one case, he humiliated a young woman who was the subject of an article, despite the fact that his reporter had turned in a sympathetic profile. This editor, now a media critic, changed the reporter’s copy to make the subject look like what the paper called “the freak of the week.”

Then there was the time that journalist Andrew Beaujon, now at The Washingtonian, wanted to do a story about me. As I recalled at the time, Beaujon was tweeting nasty things about me while he was preparing for the interview. He’d made up his mind to trash me before we even spoke for the first time.

Mike Riggs, a journalist at Reason, recently tweeted a thread about his own history of violence and condemning Gianforte.

Some excerpts:

Some thoughts on macho talk re: the Montana incident. The idea that real men occasionally hit, and that real men hit back, is bad for men.

By the time I hit adolescence, my aunt told me one day that my family had considered sending me away because of how violent I was.

The sons of "real men" grow up to be emotionally stunted, confused, and poor.

Real men do everything they can to avoid hurting others and themselves. Self-restraint and wisdom are not weak, they are powerful.

Our prisons are full of "real men.”

This is powerful stuff. But it reminded me that Riggs was once a writer for Washington City Paper, which has a long history of reporters acting dishonorably with their subjects. I once wrote for City Paper, but over the years was disturbed by the frequent letters the paper always got from people claiming they had been slandered. Even the late David Carr, the late-1990s editor of City Paper, used to dismiss complaints from people as gripes form the paper’s “freak of the week” feature.” These were real people whose lives had been hurt.

These are just a few examples that I experienced in my interactions with journalists. I sometimes wonder: if that’s my experience, how many more similar stories are out there, and not from people who can’t fight back, but from innocent victims?

From all appearances, Ben Jacobs is an innocent reporter who got assaulted. But if journalists are interested in learning from this incident, they will finally examine some of their own dishonorable behavior.