It’s so typical of now: factual claims are made; substantive policy issues are raised; then the whole of the subsequent discussions turns on the fact that, according to some group of pinheads, the wrong word was used. The pinheads are offended. Everyone screams for a few days, and says over and over again that words matter. Then we never have the policy discussion at all. Why? Because words matter, but other things, evidently, don’t. Because only words matter, or only words exist, and political power is a matter of controlling the words. I propose the words of people who say that words matter don’t matter. They're just trying to manipulate you with their vacuous yapping.

“I think spying did occur, yes. I think spying did occur,” said Attorney General William Barr, apropos of FBI surveillance of people connected to the 2016 Trump campaign.

"I don't know what the hell he's talking about," replied former domestic spy chief James Comey. What the FBI did, he said, was court-approved surveillance. "I've never thought of that as spying." Perhaps he has; perhaps he hasn't.

This isn’t the most important thing, but Barr used the term accurately. Let's say I'm watching you, carefully, following you around, obtaining your communications without your permission, and so on. That’s spying in the common acceptation of the term, whether you have a warrant or not. The Oxford dictionary defines spying as secretly obtaining information on behalf of a government, or as observing someone furtively or clandestinely. They leave out the stuff about whether you have a warrant, and the stuff about how you can't, by definition, be spied on by the FBI, because spying is bad, but the FBI is good.

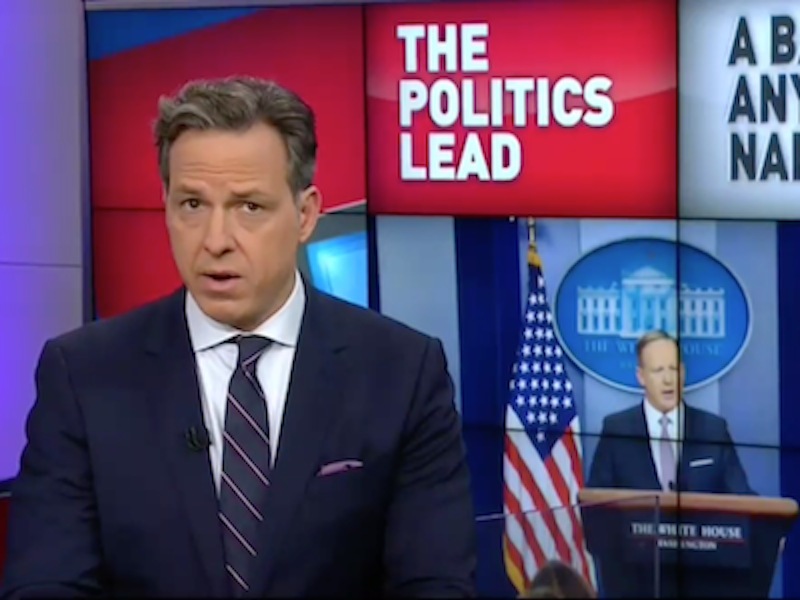

CNN and MSNBC are police channels or law enforcement propaganda operations. They roll out a series of former prosecutors, former CIA and FBI agents, former Pentagon spokespersons, once and future cops. The point of view of a number of the anchors and reporters—Jim Sciutto, Jake Tapper, and Nicole Wallace, for example—are indistinguishable from those of these guests and contributors.

CNN on a bad day begins to sound like an FBI operation. In this case, their guests, reporters, anchors and contributors were unanimously outraged; they spent a couple of days pretending, with Comey, not to understand what Barr was talking about. Then they dropped it without even touching on the terrible problems raised by surveillance, authorized through proper channels or not, in the context of political campaigns. They succeeded again in not letting a discussion emerge of the real issues on their channels. That's what “words matter” is for: distraction.

I’ll seem to be taking both sides on this; bear with me. The FBI and other intelligence agencies had every reason to investigate Russian interference in the 2016 election and whether people in the Trump campaign—or any other "American persons"—were complicit in it. But Barr is right, as well, that surveillance of the Trump campaign needs to be investigated.

More widely, we’d better reflect carefully on the role that the Justice Department and intelligence agencies play in the electoral process in an era when every American's communications are potentially available for examination. And those agencies had better reflect on their own role, for they’ve repeatedly embarrassed themselves. In various ways, their decisions may have helped decide the 2016 election, but the approach was merely confused, reflecting no systematic or rational policy with regard to the many points at which intelligence-gathering intersects politics.

The need to develop such policies, and to reflect on the role of law enforcement and intelligence in the electoral process, is urgent in a context where such agencies have the ability to monitor or reconstruct the communications of any or all of us, including our leaders and politicians. But the deepest reflection that law enforcement and intel spokespeople such as CNN and MSNBC can muster is, "He used the wrong word!" He didn't, but even if he did, that’s not the problem, unless you’re a CIA PR flak such as Jim Sciutto.

Comey, as FBI director, went public twice in 2016 with the results of the Hillary Clinton email investigation, in what amounted to interventions in the campaign at key moments, including in its last week, when he announced that the investigation was being re-opened on the basis of materials found on Anthony Weiner's computer. At the same time, the agency was relatively uncommunicative about the fact that they were investigating Trump, and had a number of his associates under surveillance, even as materials relevant to that investigation—the Steele dossier, for example—leaked. These were precisely the decisions that led Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein to advocate Comey's dismissal, which in turn set off the Mueller investigation.

Conspiracy theorists on both sides see in these events evidence that the intelligence community was trying to throw the election one way or another. They look to me more like bewildered attempts to muddle through. But they make one thing obvious: intel agencies and the Justice Department are in a position to control elections, by determining whom to investigate, whose communications to monitor, and what to make public when, either directly or by leaks. A strategic plan to leak material one way or another, or even merely to announce investigations, or not to, could prove decisive in 2020, with regard to any election for any office.

From the early days of the 2016 campaign, the FBI had associates of Trump under surveillance, and hence had indirect access to various communications snaking their way through the campaign to Trump himself. This is the truth behind the claim by Trump that Barack Obama "had my wires tapped." Then they gained access to communications retroactively from people around Trump, such as Michael Cohen and Paul Manafort, reading and hearing many of Trump's own communications.

Now, whether all this investigation was warranted, and whether it reflected political partisanship on the part of the investigators, is a matter that ought to be examined carefully, in detail. Even if the investigation was justified and conducted in a non-partisan way, however, the whole thing makes it obvious that, in constituting something like universal surveillance after 9/11, we created a force which can potentially control the electoral process, or which can just blunder around and determine who is president by accident.

We do need an investigation of the investigation, in other words. We need a clear set of policies or limitations setting out ways intelligence agencies can legitimately operate to help guarantee the integrity of elections, while keeping the agencies from compromising that integrity themselves.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell