Imagine that a friend and you are so desperate for cash that you discuss the possibility of robbing a bank together. You then go to the bank to check it out, but taking this action brings you to your senses. Perhaps you breathe a sigh of relief that you didn't lose your mind and become a felon, but you're wrong. You're already guilty of conspiracy to commit bank robbery, which under American law means you discussed a crime and then took an action—only one action is necessary—towards carrying out the crime. That action could merely have been buying a ski mask.

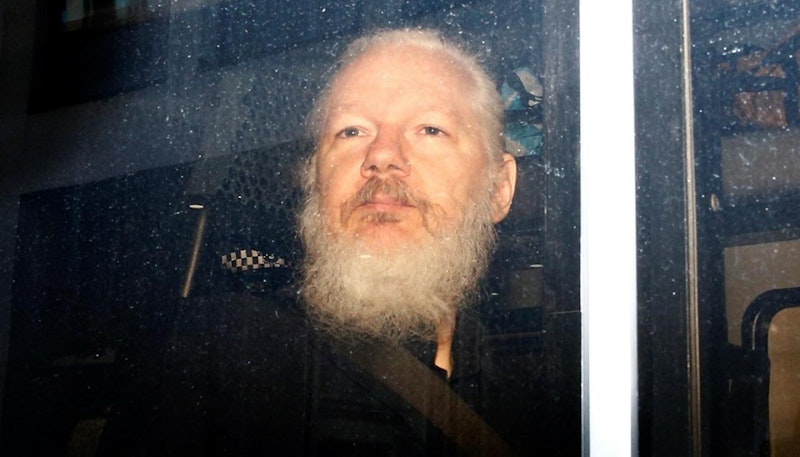

Questions surround last week’s arrest of Julian Assange in London. Is it a threat to the free press? Is the infamous leaker a journalist? Should the UK extradite him to the US? One key angle that's neglected is that the US government doesn't have enough evidence to charge him with committing an actual crime. He's charged with “conspiracy” to hack into US government computers. His co-conspirator is allegedly Chelsea Manning, a US government whistleblower whose 35-year prison sentence President Obama commuted after she'd served seven years in a military prison.

Assange and Manning are suspected of trying to crack passwords to get into classified computers, but the US government isn't alleging that they succeeded. The indictment's based on old chat logs that have been publicly available for years, in which two people the feds believe are Assange and Manning are merely discussing the possibility of a crime.

Federal prosecutors don’t have enough evidence to indict Assange for carrying out a crime but still might get him extradited to the US for some online chats. This point will surely play a prominent role in the extended extradition battle that will soon play out, presumably with Assange residing in a British prison.

There are dozens of federal conspiracy statutes on the books. Some of them carry a maximum of five years in prison, but drug trafficking, terrorist, and racketeering conspiracy convictions carry the same penalties as their underlying offenses. Where's the justice in punishing someone who just made some plans to commit a crime just as harshly as a person who went ahead and did it? The government doesn't even have to produce a co-conspirator if it has evidence suggesting that a conspiracy occurred. It's all stacked to favor the state over the individual.

Since conspiracy is a separate crime, it may be prosecuted following a conviction for the underlying crime without being in violation of constitutional double jeopardy provisions. Such a legal travesty's only possible when actions that fall short of crimes are designated as crimes. It's like Catholic nuns telling their students that just to ponder certain “impure” thoughts is a sin, just like acting on them would be.

For the imaginary bank-robbing scheme above, let's say you talk about doing it online, case the bank, but finally give up. You've done the exact same thing as the two people in the earlier example, but you're in luck this time because there are no one-person conspiracy charges. Does that sound arbitrary? Where’s the logic in saying that individual people are not legally capable of committing a certain crime?

The US has experienced a conspiracy law creep. The laws were first narrowly tailored, but then expanded in scope in order to police the actions of corporations, organized criminal enterprises, and labor unions. You see a similar development with RICO laws, originally crafted to target organized crime but then misused by overzealous prosecutors to go after individuals. Legislators must be aware, when writing laws, that prosecutors don’t give a damn why a law was written. They'll use it in any way that suits them, and maximizing their convictions is what suits them the most.

Prosecutors have incentive to charge people with conspiracy. Once they've identified someone as part of a conspiracy, they can then charge them for every reasonably foreseeable crime done by all the other co-conspirators. Without carrying out one actual crime, someone can be charged with multiple crimes without even knowing about those crimes or assisting in their commission.

Obama's DOJ had access to the information used to indict Assange since 2011, but declined, citing freedom of the press concerns. A troubling aspect of the Trump DOJ indictment is that it's calling normal journalistic practices, like Assange's and Manning's use of Jabber, an encrypted messaging service that guarantees anonymity, part of a “conspiracy.” The DOJ's claiming that this was an attempt to conceal Manning as the source of material released by WikiLeaks. Journalists, however, are ethically required to protect their sources. If protecting sources is now going to be considered a crime, government will have broken the free press.

The federal government doesn’t have a sound basis to demand the UK extradite Assange to the US. If the Brits acquiesce, they'll be striking a blow against the free press at a time when the US president's intent on delegitimizing it.