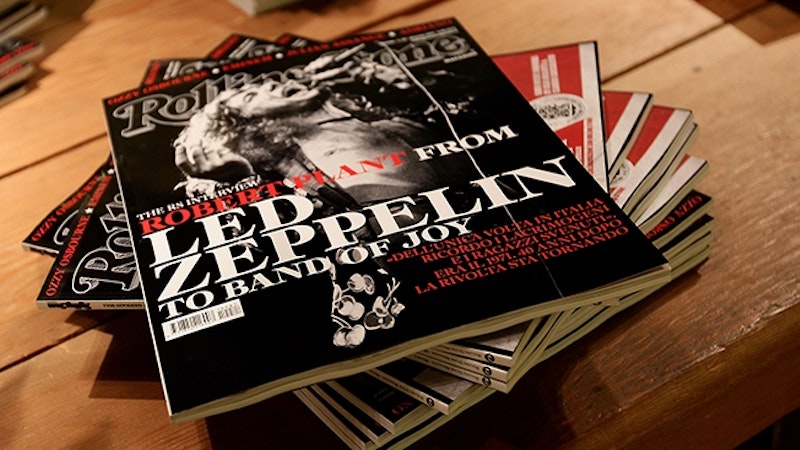

My alma mater's quarterly alumni magazine recently adopted a new, more durable format. Cover pages are thicker and rougher, and overall, each issue is longer than before. In the past, rolling one up to dispatch a single fly might destroy the magazine; today, one can get away with a good five or six months of glossily aspirational murder. What all of this amounts to is that the alumni magazine is now a more formidable periodical than the physical edition of Rolling Stone.

At some point in the last few years, after its dimensions had receded drastically in every way, Rolling Stone was granted a flat spine. This had the effect of conferring substantiality to the magazine that many would argue was already hemorrhaging; it felt wrongheaded, and a little desperate. Books, after all, had spines. Thus readers were subliminally encouraged to hang on their copies, to shelve new editions alongside The Corrections and Robinson Crusoe and The Beautiful Struggle instead of donating them to charity or leaving them to curdle and yellow atop toilet tanks.

Rolling Stone abandoned the illusory pretense of a spine this spring. I’m considering the latest issue now. It’s brutally thin. Cover subject James Franco gazes into my eyes ruggedly, a little pensive, and I return his gaze, and it’s as though we’re asking one another the same question mentally: “What became of Rolling Stone, bro?” But the answers are too self-evident, depressing, and boring to list, even as the review sections whither and the political coverage (mostly) remains solid enough. The only thing sadder and lonelier than surrendering publishing’s mastodons to the content-provider void is watching them waste away; the only question worth asking, now, is what the final stage of wasting away looks like. A brochure? A pamphlet? A broadside? How long and how painfully can the delusion of print be sustained?