When Walter Winchell died in 1972, there was one mourner at his funeral—his daughter Walda. The journalist's luster had faded well before he went to his grave, but at his peak two-thirds of the American adult population either read Winchell's syndicated daily column that ran in over 2000 newspapers or listened to his weekly radio broadcast. His appeal as a personality was once so broad that Hollywood coaxed him out to the West Coast from New York City to star in two successful movies.

FDR invited Winchell to the White House. FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover liked hanging out with him in posh Manhattan nightclubs. Although Winchell's career left an indelible mark on journalism and popular culture, he squandered the good will he'd accumulated over decades. His was a rags-to-riches-to-forgotten story of a man who'd gotten drunk on his own power, picked too many bad fights, and couldn't adjust to a new media era.

For 40 years, Winchell was the most famous and detested "gossip columnist" in America, although his material eventually expanded well beyond merely gossip and into national and international affairs. It's difficult to understand the 20th century without understanding Winchell. Without the Harlem-born journalist's brash approach to breaking taboos, there'd be no Page Six in the New York Post, no TMZ, and no Entertainment Tonight on TV. Many would say we'd be better off without the entire tabloid mentality, and they’d have a point. Winchell's legacy is not without its dark side, which Neal Gabler’s biography—Winchell: Gossip, Power, and the Culture of Celebrity—captures in great depth.

Plenty of 15-year-olds keep up with who Khloe Kardashian is canoodling with in L.A. hotspots, or the the actor with a DUI bust, but they don't realize that they're partaking in the modern culture of celebrity that Winchell invented in the 1920s when he was writing his original, punchy prose for the New York tabloids, and later with the Hearst newspaper chain. He was a different sort of journalist from the get-go―untrained and unfettered by convention, with his own slang that made readers feel they were privy to insider talk. Couples having a baby “got storked." Jews (he was one) were “Joosh.” Lovemaking was “making whoopee, "booze” was “giggle water,” and Nazis were “Ratzis.”

Baltimore newspaperman H.L.Mencken, spare with praise, gave Winchell credit for expanding the American vernacular. The playfulness of his language coupled with the semi-illicit nature of his material caught the nation's attention. It was as if he'd invented a journalistic format they'd been longing for unconsciously. Winchell’s column was a fun read, chock-full of juicy tidbits. He reported on impending divorces, who was having money problems or affairs, and other peccadilloes of the famous. Winchell became as famous as the stars he tattled on.

Before Winchell, the public couldn't get the lowdown on the celebs they had love/hate relationships with because newspapers had always feared such personal muckraking would cross the line into salaciousness. Winchell recognized no such demarcation―private lives were fair game if he had a scoop. This groundbreaking approach made him both famous and reviled throughout his career. But Winchell wore the derision like a badge of honor, for he fancied himself a man of the people, giving them ("Mr. and Mrs. America" is what he called them on his radio show) what they wanted. He had no interest in occupying journalistic ivory towers, nor did he display affection for the celebrities he dished and angered. He never stopped embracing his outsider status.

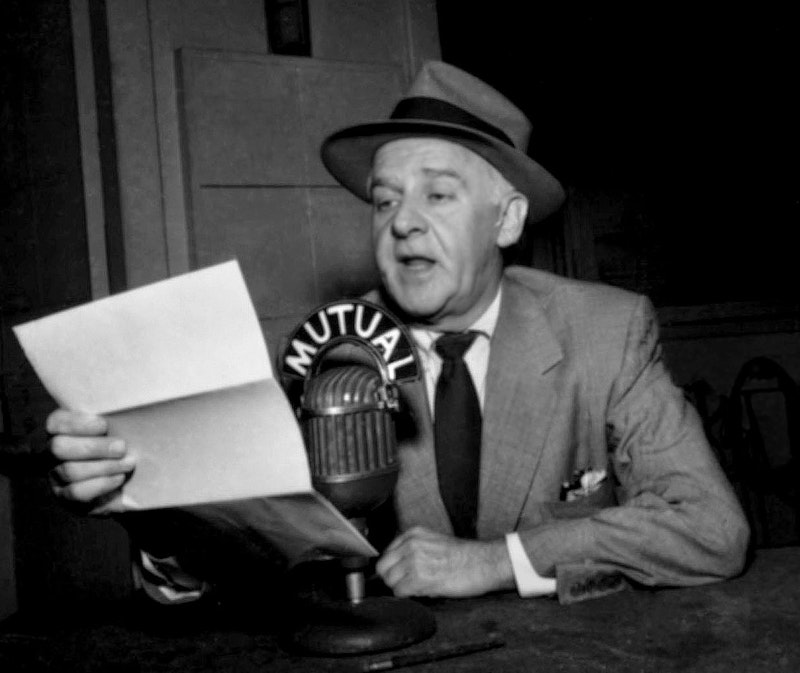

Winchell cut a figure with his clipped staccato voice, a snap-brim fedora, and cigarette dangling from his mouth. His style set the tone for the fast-talking urban male of his time, and he was out every night. One of his "offices" was table 50 at Manhattan's refuge for Cafe Society, the Stork Club, where he’d hold court like a count. Hollywood stars would stop by to chat, and so would mobsters, prizefighters and socialites. They'd all deliver tips that would make it into his daily column—the column that consumed him for so many years.

Had Winchell's career ended in the mid-1940s, he’d have gone out on top, revered as the greatest journalistic force of his time, a show business phenomenon, and a political influencer. Winchell was a fan of FDR and his New Deal, and a fierce critic of Hitler and fascism, but then communism came along. Winchell’s hatred for communists brought out his worst personality traits (e.g. mean-spiritedness, egomania). It led to his association with Machiavellian New York lawyer, Roy Cohn, and to Cohn's boss, Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his anti-communist witch hunt.

Instead of using his power as a steadying force for the nation during the Cold War, Winchell morphed into J.J. Hunsecker, the ruthless character played by Burt Lancaster in the 1957 film, The Sweet Smell of Success, a role that was modeled after the columnist. Convinced of his duty to save the nation, he attacked and allied with the wrong people. And then television came along and he couldn't make the transition. Winchell was from a different time, as his outdated fedora telegraphed. TV audiences noticed.

The lovable rogue became the loathsome red-baiter, and the two-decade slide into oblivion began. Small humiliations followed small humiliations. Ernest Hemingway once called Winchell the “only reporter who could last three rounds with the zeitgeist.” But Winchell, who once was inseparable from the zeitgeist, would end up as an anachronism―a sad example of the dangers of populism when allowed to run amok.