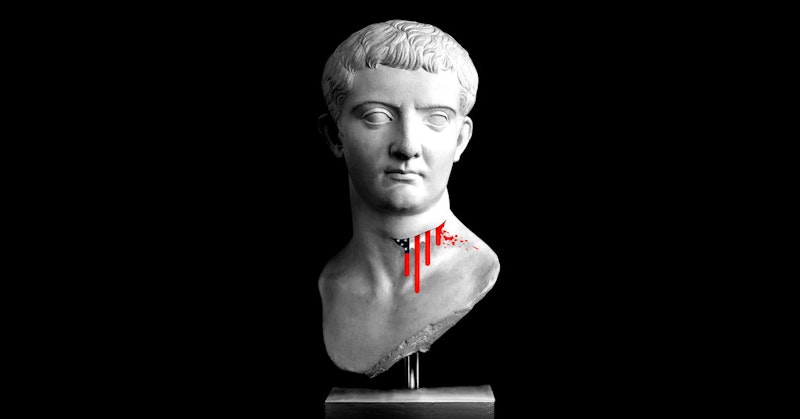

Viewing American life from the outside, it took me some time to grasp one of the country’s peculiarities: a low-grade obsession with patterning itself after Rome. You hear it in political rhetoric. You see it in the way the United States imagines itself: the symbol of the eagle, the architecture of structures like the Capitol and the White House, the government consciously based on the Roman Republic. But the Roman Republic gave way to an Empire after decades of strife. What does that say about the future of the American republic?

Edward J. Watts presents some thoughts in his book Mortal Republic: How Rome Fell Into Tyranny. It’s a brief history of Rome from the Punic Wars to the Republic’s collapse into Empire, roughly 250 years of history. The book’s necessarily a high-altitude view of the period, but Watts tells a coherent story.

The gist of Mortal Republic is that the government of the Roman Republic was well-adapted to survive and grow, but not adequate to deal with the pressures of wealth and inequality that followed military triumph. In Watts’ telling, patriotic unity dissolved under power politics until an every-man-for-himself mentality eroded norms and corrupted the functioning of Roman government. All of which undersells the character and color of Watts’ book, but gives a sense of the themes that structure his reading of Rome’s history.

Watts isn’t shy about finding modern-day parallels to Rome: “The ancient Roman Republic is, of course, very different from a modern state, but the Roman Republic’s distribution of power and its processes for political decision making deeply influenced its modern descendants,” he writes in a Preface. “The successes and failures of Rome’s republic can show how republics built on Rome’s model might respond to particular stresses. They also reveal which political behaviors prove particularly corrosive to a republic’s long-term health. I hope that this book allows its readers to better appreciate the serious problems that result both from politicians who breach a republic’s political norms and from citizens who choose not to punish them for doing so.”

As this indicates, there’s a streak of idealism in the book. Watts argues that the Empire came about because over the course of decades politicians in the Republic made a series of choices that were born of self-interest instead of patriotism, and were enabled by the people of Rome. It’s a fair point, but when he goes on to argue that this meant the Empire was not an inevitability, one must wonder. If politicians over generations consistently made self-interested choices and thrived as a result, doesn’t this mean the system in which they were acting encouraged those choices? Watts doesn’t investigate this possibility, which leaves the book occasionally feeling superficial.

Still, it’s hard not to see parallels to contemporary America in his description of Rome. This is a story of a small polity which grew by an interlinking of militarism and patriotism, expanding its control first by alliances and then by force through the land-mass around it; before long it projected its power overseas; its own success led to a tiny wealthy elite lording it over masses of the poor; that elite consistently took political action to guard their power and privilege; and eventually true democratic elements in government were eliminated, leaving only a facade through which an emperor could exercise power as he wished.

One might dispute whether some of Watts’ more specific arguments about Roman history apply to the present. In his reading, the Gracchi—second-century tribunes, brothers, who tried to pass land reform laws to undo increasing inequality—were ultimately harmful to Rome because Tiberius Gracchus, the elder, injected threats of violence into the political process. For Watts, this was a key point where Roman politics changed. Watts describes Tiberius as a chancer, someone using the grievances of the poor to get ahead in politics. This seems to underrate the actual grievances of the poor. Would a better system not have found a way to eliminate violence from government after it had been introduced? And was the violence due to the actions of individual leaders, or because Roman systems had produced a situation that could not be remedied any other way?

If Mortal Republic leans toward a great-man theory of politics, it also assumes those men are always self-interested. That’s often a safe assumption to make with politicians, but the interaction of self-interest and ideals can be complex: a politician can advance a cause both to further their own political career and also because they believe in it. Watts avoids talking about ideals, with the perhaps unintended effect that this distances the book from a contemporary political scene in which different politicians have very different ideas about their country.

Does the parallel of Rome and America work as a whole? Of course there will be differences between any two republics; how ethnic and cultural diversity functioned in Rome and function in America, for example. On the other hand, any two sufficiently complex data sets will present correspondences; consider the significance of religion to both Roman and American political life. If the book’s about Rome as an analogue to the United States, do the substantial parallels outweigh the differences and the coincidental similarities?

Maybe not, but if Rome doesn’t have a one-to-one parallel to the modern United States it can at least serve as a cautionary tale. Rome was a product of a more violent and less technologically connected world than the United States. There isn’t really a similarity in American political life to the way Roman armies became private forces of their generals. But one looks at the rise of a company like Academi (the former Xe and former Blackwater) and worries.

Like families, every unhappy republic is unhappy in its own way. Still, Mortal Republic’s a good argument that similarities can be found—particularly when one republic’s descended from another. It’s a reminder that even if America and other modern republics have more tools than Rome to prevent the rise of autocracy, that means nothing if they’re not prepared to use them.