Lin-Manuel Miranda, in his extraordinary Hamilton: An American Musical, brilliantly captures Aaron Burr in three lines, the free advice he has Burr offer to Alexander Hamilton when they first meet in 1776:

Talk less.

Smile more.

Don’t let them know what you’re against or what you’re for.

Around twilight on June 7, 1812, a 56-year-old man returned from six years’ self-imposed European exile. He landed in New York somewhere near today’s South Street Seaport. He hastened to a friend’s house at 66 Water St., only to find no one at home. Only around midnight did he find a room—already occupied by five other men—in “’a plain house’ along a dark alley.” In the morning, he returned to find his friend, Samuel Swartwout, at home, and, after an affectionate welcome, the Swartwout brothers lodged him.

The charm that had borne him up throughout his life remained potent. A boyhood friend and long-time political opponent, Robert Troup, lent him $10 and a law library. Then, $10 was real money. Then, as now, a law library is essential to one’s practice. He rented space at 9 Nassau St. He took out some newspaper advertisements. He ordered a small tin sign, “brightly lacquered,” bearing his name, and tacked it to the outside wall. When he arrived to open his office on the morning of July 5, 1812, a line of clients awaited him. Hundreds more would follow. Within 12 days, his receipts totaled what was then a staggering $2000. “However the inhabitants of New York viewed… the man,” Milton Lomask wrote, “they had not forgotten the skills of… the advocate.”

Thus, Aaron Burr, former Colonel in the army of the Revolution; former Attorney General of New York; former United States Senator; and former Vice President of the United States, resumed the practice of law.

He’d been born February 6, 1756 in Newark, New Jersey. He entered Princeton in the sophomore class at 13, took his degree with distinction at 16, and even spoke at commencement.

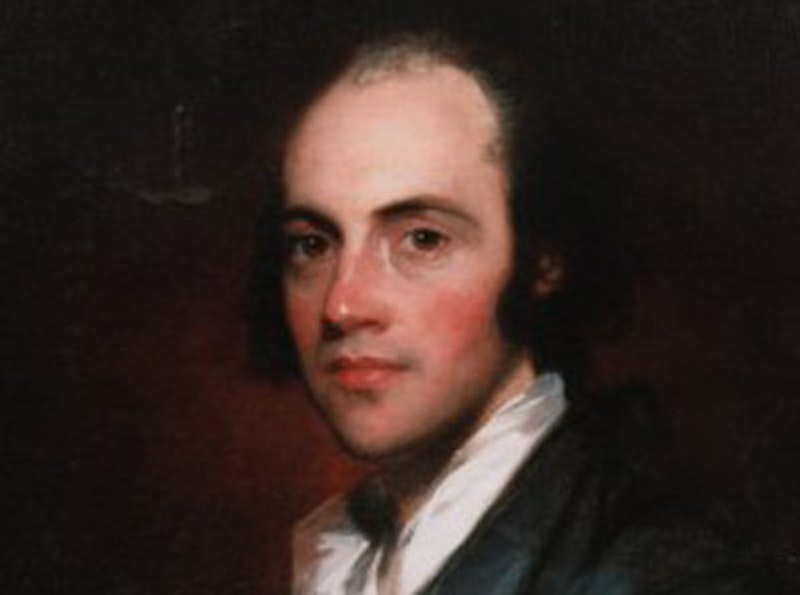

He was elegant from youth: small, slender, broad-shouldered, and handsome. He had fine taste in clothes, to which dozens of unpaid tailors on two continents would attest. His manners were exquisite, his conversation never palled, and whether in the courtroom or the Senate, he spoke quietly and conversationally, without bombast or literary allusion. He strove to see things as they are, not as they ought to be, and possessed a massive savoir faire: “… dexterity enough to conceal the truth, without telling a lie; sagacity enough to read other people’s countenances; and serenity enough not to let them discover anything by yours.” He was also throughout his life pursued by women, and they never had to run very far or very fast.

He fought for American independence at Quebec, Brooklyn, and Morningside Heights. He was a lieutenant colonel at 22, wintered at Valley Forge, and had a horse shot from under him at Monmouth on June 28, 1778. That means he’d gone in harm’s way, for he might have been hit by the shot that killed his charger. Only one who has been thrown from a horse can understand that means: the pain of having the wind knocked out of you, if not muscles sprained and bones broken.

The man of pleasure once single-handedly suppressed a mutiny in his regiment. A ringleader leveled his musket at Burr, shouting, “Now is the time, my brave boys.” The last syllable had barely left his lips when Burr, having drawn his sword, severed the man’s arm, just above the elbow. The regiment knew no more mutinies.

During his service, he met Theodosia Prevost, the wife of a British officer serving in the West Indies. Burr later wrote that she possessed “the truest heart, the ripest intellect, and the most winning manners of any woman” he ever met. She spoke French fluently, frequently quoted the Latin poets, and read avidly. Burr admired and wanted her. She responded with warmth and friendship.

Her husband died in 1781. She married Burr the following year. Nothing so testifies to Theodosia Prevost’s character, charm, and intelligence than that this sensual, cynical man was throughout their marriage her loving, faithful husband. More, though Burr was a feminist by instinct—he admired Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women and kept a print of Mrs. Wollstonecraft’s portrait on his wall—his marriage made those beliefs heartfelt. He was among the first practical politicians—and Burr was nothing if not practical—to work for women’s education on a par with men. “It was a knowledge of your mind,” he wrote to her, “which first inspired me… the ideas which you have often heard me express in favor of female intellectual powers are founded on what I have …seen… in you.”

She died in 1794 after 12 years of marriage. He never ceased to mourn her. Perhaps their relationship was the noblest achievement of his life. In Hamilton, Burr is asked, “…if you stand for nothing, what will you fall for?” Clearly, at least in his love for Theodosia and his passion for human rights, he stood for something.

In 1782, he was admitted to the New York bar at the age of 26. He was elected to the Legislature in 1784, at 28, where he fought to abolish slavery, and appointed Attorney General in 1789, when he was 33. In 1791, he defeated Philip Schuyler, father-in-law of Alexander Hamilton, for the United States Senate. Thus the feud between Hamilton and Burr began.

The new Senator worked hard without taking politics seriously. For him, it was the pursuit of “fun and honor & profit.” This earned him the antipathy of Thomas Jefferson, who took politics almost as seriously as he did himself (to be fair, perhaps not entirely true: we know Jefferson had red hair in part because he preserved a letter addressed to him as “You red-headed son-of-a-bitch.”).

Yet the Virginian and Burr needed one another. Burr controlled the country’s first mass party organization: the Society of St. Tammany. If Jefferson was the Democrats’ first ideologue, Burr was their first mechanic.

In 1800, the Jeffersonians nominated Senator Burr for vice president and his troubles began. Presidential electors then voted for two candidates without specifying a preference for president and for vice president. The candidate receiving the most votes became president; the second-place candidate became vice president. Jefferson and Burr tied with 73 votes each. The election went to the House of Representatives.

The Federalists, who detested Jefferson, sought to elect Burr instead. The House elected Jefferson President and Burr Vice President after 36 ballots.

There is no evidence that Burr had plotted with the Federalists to win the Presidency. Nonetheless, Jefferson, who always had a slight touch of paranoia, froze him out and withheld patronage from his followers. In April 1804, Burr, knowing Jefferson would not allow his re-nomination later that year, ran for Governor of New York. Hamilton had come to hate Burr, and Hamilton’s rage was reflected in his intensely personal campaigning, which included indiscreet personal remarks reported in the newspapers. Burr was heavily defeated.

Burr seized upon correspondence published in the Albany Register. Dr. Charles Cooper wrote, “General Hamilton and Judge Kent have declared, in substance, that they looked upon Mr. Burr to be a dangerous man,” and “I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Burr.”

Burr requested an "acknowledgment or denial" of the "still more despicable opinion" of himself attributed to Hamilton. Two days later, Hamilton replied with a dissertation on the meaning of "despicable." Burr responded, "...the Common sense of mankind" affixed to the word “the idea of dishonor." He then demanded Hamilton generally disavow "any intention… to convey impressions derogatory to the honor of Mr. Burr."

Hamilton was trapped. This would’ve meant denying a great deal of his political conversations, speeches, and correspondence over two decades. Hamilton now feebly offered that he could not recall using any term that would justify Dr. Cooper’s construction.

Burr again demanded a disclaimer. Hamilton refused. On June 27, 1804, Burr challenged and Hamilton accepted. In Hamilton, its most stirring and poignant lyric may be one sung by the protagonist: “I am not throwing away my shot.” Yet upon the last full day of his life, that is what Hamilton did.

On Wednesday, July 11, 1804, at 7 a.m., the two men stood 10 paces apart on the Weehawken shore, pistols in hand. Hamilton, perhaps a second before his opponent, fired into the air. Burr shot true.

He was indicted for murder in New York and in New Jersey. While his lawyers and friends worked to quash the indictments, he returned to Washington, DC, where he resumed his duties as vice president.

On March 2, 1805, his last day in public office, Burr rose from the chair. He stood before a hall of professional politicians familiar with every rhetorical device, many of whom hated him. Without changing his customary conversational tone, he spoke briefly of the United States and the Senate itself. The Senate, he said, “is a sanctuary; a citadel of law, of order, and of liberty; and it is here—it is here, in this exalted refuge; here, if anywhere, will resistance be made to the storms of political frenzy and the silent arts of corruption; and if the Constitution be destined ever to perish by the sacrilegious hands of the demagogue or the usurper, which God avert, its expiring agonies will be witnessed on this floor.”

Then, having spoken for once from the heart, he stepped down, walked across the chamber, and went out the door. He was only 49 years old.

Behind him, the Senate sat in silence. Senator Samuel Mitchill of New York wrote, “My colleague, General Smith, stout and manly as he is, wept as profusely as I did. He… did not recover… for a quarter of an hour.”

Even before leaving office, Burr had begun a conspiracy. Precisely what Burr planned remains “a mystery, a puzzle, a lock without a key.” He told his first biographer, Matthew L. Davis, the scheme he called “X” was intended to “revolutionize Mexico” and settle some lands he held in Texas. Perhaps it was.

But the legends remain, and the papers tantalize: the maps of New Orleans, Veracruz, and the roads to Mexico City, and the correspondence hinting he would not liberate but seize Mexico, draw the Western states from the Union, and, combining them into one nation, stand at the throne of the Aztecs and crown himself Emperor of the West. “The gods invite us to glory and fortune," Burr wrote to his co-conspirator, General James Wilkinson, then general-in-chief of the U.S. Army. John Randolph of Roanoke, most ferocious of politicians, called Wilkinson “the mammoth of iniquity… the only man I ever saw who was from the bark to the very core a villain.” Wilkinson, whose self-designed uniforms, encrusted with gold braid and frogging, failed to conceal his enormous girth was, as we now know, a paid agent of Spain, a man on the take. At some point, Wilkinson ratted out Burr to Jefferson. On November 27, 1806, Jefferson issued a proclamation that led to the collapse of the plot, Burr's arrest, and Burr’s indictment for treason by levying war against the United States. Wilkinson was not the subject of prosecution, though we now know that Jefferson knew Wilkinson was taking money from the Spanish. Perhaps Wilkinson knew too much in an age not yet so cruel as to eliminate those who knew too much.

Burr was tried in Richmond, Virginia, before Chief Justice John Marshall, Jefferson’s third cousin (the cousins detested one other). The prosecutor insinuated that Marshall would be impeached if he didn’t rule for the prosecution on the evidentiary motions. Marshall noted the threat in his decision. He also noted the Constitution requires treason to be proven by the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act of treason. Of the dozens of witnesses presented by the government, none had testified to an overt act. Marshall then excluded all evidence presented by the government as “merely corroborative and incompetent.” Within 25 minutes, the jury found Burr not guilty.

So Burr beat the treason rap. His lawyers quashed the murder indictments. Now, in a self-imposed exercise in discretion, Burr left for Europe, traveling to England, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, and France, not to return for six years.

At first, Burr sought financial support for “X” from the British and then the French. Nothing came of it.

From the exile’s beginning, Burr recorded his experiences in a private journal, in which he reveals himself as nowhere else. Perhaps its saddest revelations are that this vital, charming man was so easily bored. Yet, as Lomask writes, “There was a limit to how many parties he could attend, how many ceremonies he could watch, how many books he could read, how many bright and articulate people he could draw within the radiant circle of his charm.”

He devoted his energies to fornication, with prostitutes if necessary and other women when possible. Lomask notes he described his amatory encounters as muse, “a French hunting term meaning ‘the beginning of the rutting season in animals.’” This suggests he despised himself for treating sex in this way.

In Copenhagen, after an unsatisfactory encounter (bad muse), Burr returned to the hotel where the chambermaid occupied his time: “not bad; muse again.” During one busy morning in Stockholm, “ma bel Marie” came by after breakfast, a Hanoverian woman at 9 a.m., and “Carolin” at 2 p.m. The former vice president admitted he would’ve been happier if Carolin had deferred her visit to the next morning. Then he ordered a bath, noting “nothing restores me after too much muse like the hot bath.”

In Paris, he noted muse was plentiful, but not always to his liking: he found Parisiennes cold and calculating, with their passions in the head and not the heart.

Yet some principles remained uncompromised despite boredom and lack of money. He never descended to drinking cheap wine.

After returning to the United States, he only dabbled in politics. In 1812, he was pulling strings for “an unknown man in the West, named Andrew Jackson, who will do credit to a commission in the army if conferred upon him.” When Jackson became President in 1829, Samuel Swartwout, whose hospitality Burr had enjoyed on his return from exile, was appointed Collector of the Port of New York with Burr’s help.

As M. R. Werner relates, Swartwout later

…hurried to Europe when his accounts showed that he had borrowed from the government’s funds…the sum of $1,225,705.69… The public, with that charming levity which has always characterized its attitude towards wholesale plunder, made the best of a bad situation by coining a new word… when a man put the government’s money into his own pocket, it was said… he had ‘Swartwouted.’

In 1833, Burr married Eliza Jumel, probably the richest American woman of the time. She had, after what may have been the most successful career of her age as, shall we say, a working girl, married an extremely wealthy man. By the time she married Burr, Madame Jumel was a widow. Burr probably married her for her money. Within the year, she began divorce proceedings upon the grounds of adultery, a remarkable, even heartening, accusation against a man of 78.

On September 14, 1836, the day on which the decree of divorce from Madame Jumel was entered by the court, Burr died in a second-floor room at Winant’s Inn, 2040 Richmond Terrace in Port Richmond, Staten Island. Two days later, he was buried beside his father and grandfather in Princeton, New Jersey. Lomask wrote, “For nearly twenty years the grave went unmarked. Then a relative arranged for the installation of a simple marble slab.” In 1995, the Aaron Burr Association placed a bronze plaque on the grave that recites his services to the Republic.