The difference between the Ferguson, MO, of today and Maryland’s Eastern Shore of 50 years ago is the stark contrast of bullets vs. ballots.

The torch-light of Molotov cocktails, the irritant cloud layers of tear gas and the lethal rifle muzzles searing across television screens in recent weeks are vaguely reminiscent of the 1960s when Maryland’s Eastern Shore became a civil rights flashpoint and an armed camp for nearly two years until blacks were allowed to vote in Cambridge and college students were given check-cashing privileges in Princess Anne.

In Ferguson, a small majority-black Missouri municipality on the outer edge of St. Louis, a teenager’s body riddled with six bullets has rallied the town’s black community into a united cause for proportional representation as well as a fair hearing on the death of the slain Michael Brown who was cut down by a policeman’s gun.

Outliers have turned the peaceful protests into a riotous occasion for an unnecessary ruckus and law enforcement showdown. Ferguson’s staging area for protests is a quarter mile zone called Florissant Ave., where demonstrators square off nightly against police. A majority of the 167 persons who were arrested were interlopers.

What Maryland’s demonstrations were all about seem so distant and quaint, in part because they lacked the immediacy of today’s plugged-in world and the mobilizing force of Twitter and cable TV and even the street cadences of hip-hop artists. Except that in Maryland no one was shot, police and National Guardsmen were not pelted with rocks and bottles, military hardware was probably not loaded and there was little or no looting except when outsiders appeared to agitate the Maryland cause.

Civil rights activists from across the nation poured into the tiny waterside town, notably two of the incendiaries of the era, Stokley Carmichael and H. Rap Brown. Brown, a Black Panther leader, encouraged the torching of the largely black Second Ward which was later rebuilt. (Several years later, Brown was associated with the fire-bombing of a church in Cambridge. He was killed when the car he was driving detonated and scattered his body across a Harford County highway. Brown’s identity was determined by his teeth.)

Sifting through the cobwebs of 50 years, the civil rights era began in Maryland when Gov. Millard J. Tawes (1959-67), an Eastern Shoreman from Crisfield, unleashed snarling State Police K-9 dogs on students from the historically black University State College (Now the University of Maryland Eastern Shore) who took to the streets because local banks refused to cash their personal checks.

The fight for rights continued through the accommodating weather of 1963-64, and again in 1967, with blacks marching nightly in Cambridge to demand America’s most fundamental right—the right to vote which they were denied in the sleepy cannery town halfway down the Eastern Shore at the headwaters of what H. L. Mencken described as “Transchoptankia.” Tawes again dispatched law enforcement brigades, this time National Guard troops, who would bivouac in Cambridge on-and-off for nearly two years.

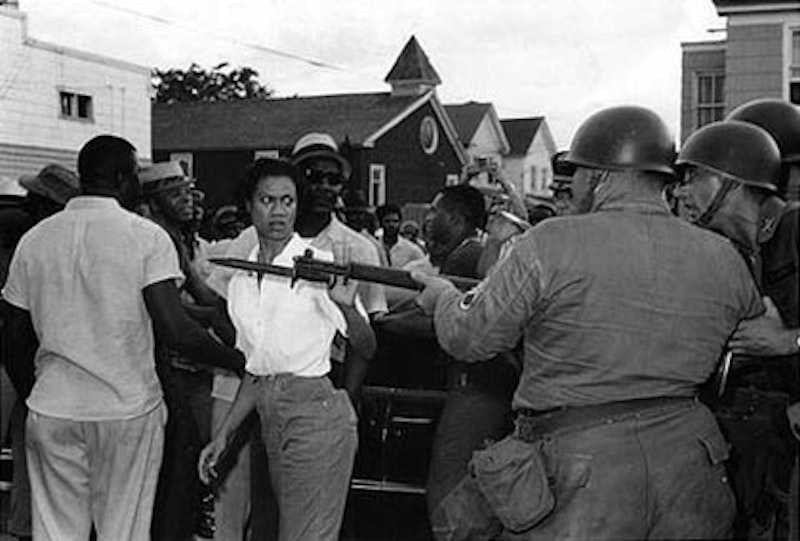

Stakeout journalism is costly loitering. Every afternoon at one o’clock during those steamy summers, black leaders, led by local firebrand Gloria Richardson, announced that they would march at seven p.m. to the town’s dividing line, described repeatedly in news accounts as “ironically named” Race St. And every evening by eight, disobeying National Guard orders to disband and go home, the black demonstrators were repulsed by tear gas and scattered back to their neighborhoods, never to cross Race St. into Cambridge’s white warrens.

Quietly and almost furtively, Tawes had also ensconced a top political aide, Ejner J. Johnson, in Cambridge to negotiate a local referendum on extending the voting franchise to blacks. Though soon discovered by reporters, Johnson operated for weeks out of the attic of a sympathetic townsman’s house and finally engineered an agreement to hold a special election on voting rights for blacks. The ballot question was defeated. Tawes had suffered another humiliating public (and human) relations disaster.

But Tawes had double trouble. At the State House in Annapolis, early attempts to enact public accommodation legislation were thwarted by Eastern Shore legislators as well as by black attempts to adopt it. During the 1962 session, Tawes and House leaders had gathered enough votes to pass public accommodations along with an agreement with black legislators that they would remain silent during floor debate.

But Verda F. Welcome, a black Baltimore delegate and later a senator, broke the agreement as well as her silence. She insisted on speaking and the more she talked the more white legislators switched their votes from yea to nay. Welcome literally talked the bill to death.

Public accommodations returned again the next year, 1963, to resume its tortuous path and was adopted. But the nine Eastern Shore counties exempted themselves under a quaint custom called local option, leaving Cambridge still exposed to demonstrations by disappointed blacks.

As is not uncommon in the dance of legislation, the half-hearted public accommodations law became entangled with reapportionment legislation. Prior to the regular 1964 General Assembly session, Tawes convened a special two-day meeting to deal with the two combustible issues. This time he used the threat of requesting federal marshals to enforce civil rights if Eastern Shore lawmakers failed the join the rest of Maryland in opening public accommodations to blacks. The threat worked and the law now covered the entire state.

Reporters covering the social unrest in Ferguson are equipped with all sorts of electronic gadgetry that can turn on a television show or send a message around the world at the flick of a switch. Viewers are engaged in events in real time which creates instant involvement and, along with it, instant reaction.

The tools of the news trade 50 years ago were phone booths and portable typewriters. Still photographs did not pack the emotional wallop of watching a young person gunned down on the street or of hotheads tossing trash cans at cops to punctuate their anger. Nor could a viewer in the small-screen, black-and-white era get a shudder from seeing a militarized zone with police in full military battle dress or a gun barrel pointed at his Barcalounger.

A half century ago the primary news outlets for events in Cambridge were the six daily newspapers covering Maryland events—The Baltimore Sun, The Evening Sun, The News American, The Washington Post, The Washington Star and The Washington Daily News.

The news of the day usually arrived on doorsteps 24 hours later. Even television news was a day late, if at all, and more likely was a recitation of the day’s newspaper content. Readers and viewers were almost disengaged from events because they lacked immediacy and the shock that often accompanies it.

Today’s instant access to the electronic media’s vast audience also gives the aggrieved a voice to be heard and an opportunity to unburden. Thus, the confrontation in Ferguson was defused in a matter of days whereas the unrest in Cambridge extended for months, even years.

The new media is also a direct line to elected officials. It’s the way we send messages to our leaders. When Attorney General Eric Holder was dispatched to Ferguson to issue reassuring words and understanding hugs as well as a black man’s personal experiences, it was easy to see that the violence, for the most part, was coming to an end. Holder had no doubt seen the explosive events on television and Twitter. If Twitter could incite revolutions, it could also tame Ferguson.

Photo: Gloria Richardson facing off the National Guard, Cambridge, Maryland, May 1964. Photo by Fred Ward.