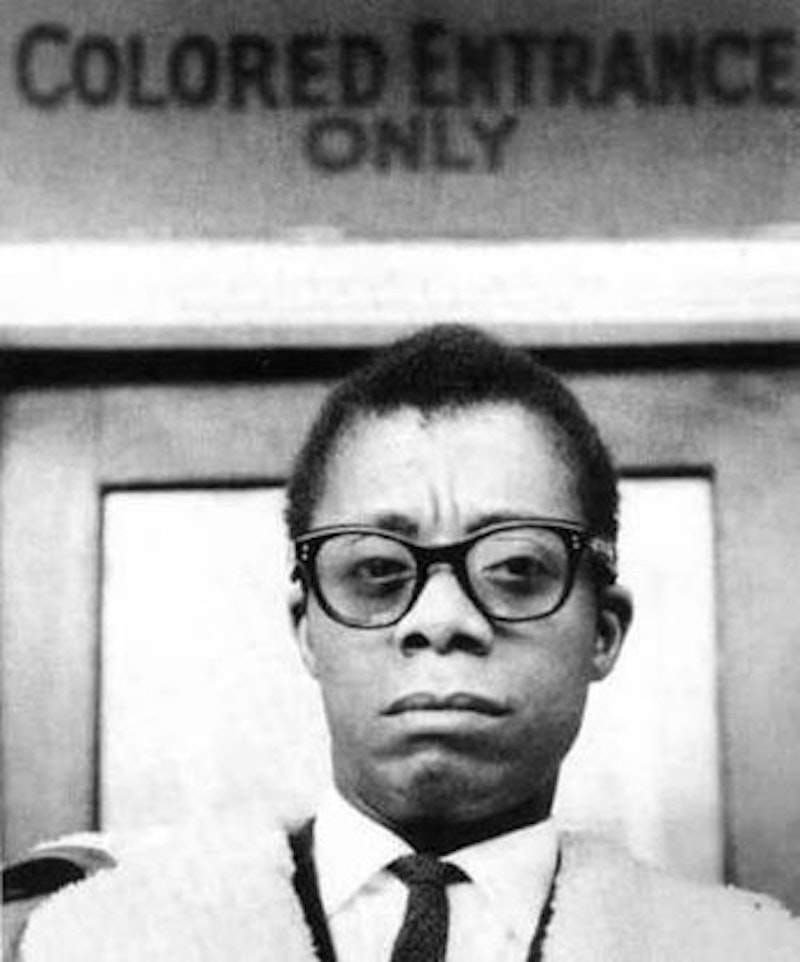

In 1942, when he was 18 years old, James Baldwin was employed at defense plants in New Jersey, "working and living among southerners, white and black", as he said in his famous essay Notes From a Native Son. It was his first sustained experience with segregated businesses; he kept going into "bars, bowling alleys, diners, places to live" and kept being told to leave. He says he became notorious; people thought he was insane, children followed behind him and laughed at him: "That year in New Jersey lives in my mind as though it were the year during which, having an unsuspected predilection for it, I first contracted some dread, chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowels." Finally, on his last night in the city, he saw a film with a white friend. They went out to eat afterwards, and, inevitably, the "American Diner" refused to serve him. In a kind of fugue of rage, he walked out, went to a very high-class restaurant, sat down, and when the waitress refused to serve him, he threw a water pitcher at her.

Baldwin wasn't killed, in part because he ran instantly, in part because his white friend had stayed with him and misdirected the police ("who arrived…at once"). But he could have easily been badly beaten, or even murdered. He could, in short, have been Mike Brown, who was gunned down by a policeman this month in Ferguson, Missouri, with, according to several eyewitness accounts, substantially less provocation than Baldwin provided to New Jersey law enforcement.

"Notes of a Native Son" is centered on the death of Baldwin's father a year after this incident, and on the 1943 Harlem riots. There are many differences between the events of 1943 recounted by Baldwin, and those of 2014. Harlem is in the city, obviously; Ferguson is an inner-ring suburb, mirroring some of the changing demographics of African-American communities over the last 60 years. The Harlem riots, Baldwin suggests, were linked to widespread bitterness, and indeed, horror, at news of how black soldiers were being treated at Army bases in the South. And, perhaps most importantly, there was widespread property damage in 1943; in Ferguson, protestors have been mostly peaceful, and have even organized to protect local businesses from opportunistic incidents of looting.

For all the differences, though, there are a lot of similarities as well. Many of Baldwin's observations seem eerily, numbingly timeless. "I had never before been so aware of policemen, on foot, on horseback, on corners, everywhere, always two by two," he says — a quick delineation of life in the occupied territory that is black America. And he goes on, "everybody felt a directionless, hopeless bitterness, as well as that panic which can scarcely be suppressed when one knows that a human being one loves is beyond one's reach, and in danger."

"Notes of a Native Son" renounces hatred and despair; in fact, the greatest threat Baldwin sees in racism and injustice is not the violence against black people's bodies, but against their souls. After he escapes from the diner and the very real possibility of being beaten to death, by civilians or police, he writes, "I saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart."

Baldwin would no doubt be inspired by Ferguson's determined reaction to Mike Brown's death, and the consistently (albeit not perfectly) peaceful response to the clumsy, ongoing police provocation. But it's hard to imagine he wouldn't also be weary: "..blackness and whiteness did not matter, to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one's own destruction," he says, which is no doubt true. But what does it say about a country that seems to believe that only blackness and whiteness matter, and to be determined to keep believing that same thing, from decade to decade, from 1943 to 2014 and beyond? "People were moving in every direction," Baldwin writes, in the moment when he left the American Diner, "but it seemed to me, in that instant, that all of the people I could see, and many more than that, were moving toward me, against me, and that everyone was white." No doubt there's been some progress in some areas since Baldwin wrote. But when you look at Ferguson, you can still see those white figures, just as Baldwin did. They're not moving forward.