My initial reaction to Maureen Dowd’s August 7th New York Times column about the president’s standoffish disinterest in political glad-handing was, all things considered, fairly schoolmarm. “Damn, Barry! You’ve got to give a little to get a little,” I tsk-tsked on Facebook.

After dropping Harvey Weinstein’s name and summoning an extended, comparative riff involving Paul Newman and the nature of celebrity, Dowd offers the following:

Stories abound of big donors who stopped giving as much or working as hard because Obama never reached out, either with a Clinton-esque warm bath of attention or Romney-esque weekend love fests and Israeli-style jaunts; of celebrities who gave concerts for his campaigns and never received thank-you notes or even his full attention during the performance; of public servants upset because they knocked themselves out at the president’s request and never got a pat on the back; of V.I.P.’s disappointed to get pictures of themselves with the president with the customary signature withheld; of politicians disaffected by the president’s penchant for not letting members of Congress or local pols stand on stage with him when he’s speaking in their state (they often watch from the audience and sometimes have to lobby just to get a shout-out); of power brokers, local and national, who felt that the president insulted them by never seeking their advice or asking them to come to the White House or ride along in the limo for a schmooze.

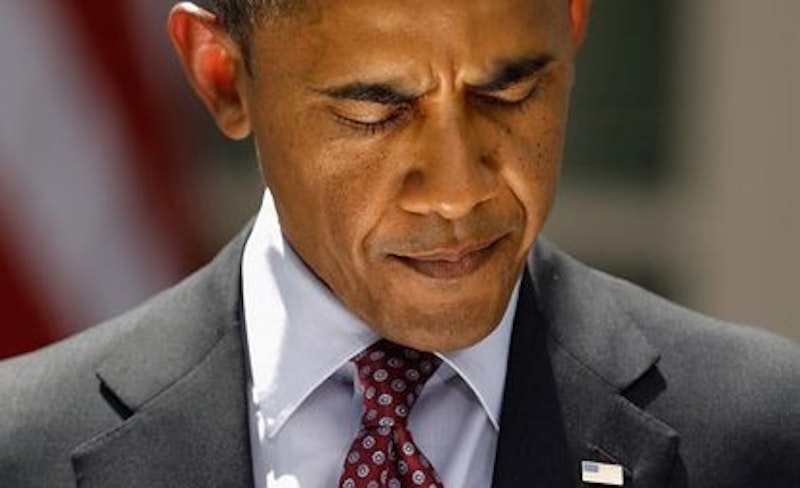

Obama emerges from this piece as one cold dude: an under-appreciative leech who also happens to be the most powerful elected official in the country. It’s easy to come away feeling some sympathy for all those rock stars and billionaires and U.S. representatives who gave so much and felt as though they got stiffed on their end of the exchange. A transformational insurgent aura, as it turns out, doesn’t necessarily translate into the sort of empathetic warmth that traditional retail politics demands.

But after a couple days of thinking all of this over, it occurred to me that maybe nobody really has a right to be aggrieved or butt-hurt over these perceived slights, that we all weren’t paying enough attention to Obama’s campaign four years ago and haven’t paid quite enough notice to the state of our nation since then. Putting aside the hope mantra, this former community organizer’s overarching message was one of hard choices, hard work, and hard times, of overcoming adversity and putting America back on the road to greatness. Around Election Day 2008, the economic crisis cannibalized the middle class, and a sort of grim stewardship headed the agenda in terms of importance; suddenly, the focus wasn’t so much on saving the world or elevating America’s world standing as it was keeping the Titanic from sinking. The first Obama term was supposed to be a big ‘ol redemptive repair job but wound up being flawed maintenance.

What I’m getting at is that being president isn’t fun; this shit is hard, and it wouldn’t surprise me if the few flashes of amusement and enjoyment Obama has displayed are suburb social theater. His natural standoffishness contributes to the sense of the man as a self-distancing pol, but there’s more. His candidacy and presidency have always been less overtly about him, and more about a larger cause. See, the idea is that everyone’s working together—college kids, Bruce Springsteen, great statesmen, MoveOn.org people who aren’t too disaffected, et al.—to make stuff better, and there isn’t necessarily enough time and energy in the day to sugarcoat and kiss ass and feed donors’ egos. Pragmatism never sleeps, and it won’t kowtow to hurt feelings. You want to rise? You want to overcome? Dry your tears, and get your ass to work. I’m sure Obama has considered saying everything I’ve just said in one form or another, but the guy probably doesn’t even have time to dictate it to anyone.