When our family moved from Manhattan to Baltimore more than eight years ago, my younger son’s new school required him to spend six weeks during the summer learning how to execute penmanship in “the Calvert way.” It struck me as rather odd: first, his handwriting was completely legible; and second, this wasn’t the 19th century, when such a skill was prized, but the digital age where every student was equipped with a laptop. (On the plus side of the ledger, eighth graders were required to study Latin, another subject largely swept into oblivion, but one that certainly has more value than calligraphy-like handwriting.)

My son was miserable—not only was he displaced from the city of his birth and friends, but also his school-appointed tutor was a pleasant, but no-nonsense elderly lady who took such matters very seriously. Day after day, he’d trudge to her apartment, barely concealing the kind of rage peculiar to eight-year-olds, and the only benefit from these two-hour sessions was that he learned a lot about birds, as the woman lived in a woody area that was thick with mourning doves, robins, bluebirds, sparrows, blackbirds, cardinals, starlings, vultures and even the occasional Baltimore Oriole. As for his penmanship, well, it was just fine—just as it was in New York—and I’m fairly sure that Booker still harbors a grudge against the retired teacher, although, as it turned out, he actually liked the school quite a lot.

I was reminded of my son’s hiccup on the way to becoming a young man upon reading a splendid front-page story in The Wall Street Journal on Nov. 3, about a boiler room in Salt Lake City, where the U.S. Postal Service employs “hundreds” of men and women to decipher millions upon millions of letters that are so poorly addressed that specialists are required to solve the puzzle of where exactly the correspondence was meant to end up. You might think, considering the massive losses the USPS suffers each year that such mystery letters would be immediately binned, rendering the Salt Lake employees redundant. After all, stamps get pricier every couple of years (I remember as a tot when a first-class stamp cost three cents, in the pre-zip code era when twice-a-day delivery still existed), post offices are closing, it’s nearly impossible to find mailboxes on city streets, and there’s been chatter about ending Saturday mail completely, an inevitability that makes me cringe.

According to WSJ reporter Barry Newman, the number of first-class letters mailed has declined from 104 billion in 2001 to 78 billion in 2010; he says the “prime culprit” is email, but I suspect that texting contributes as well, not to mention the plain fact that Americans under the age of 30 just don’t correspond by mail anymore, and increasingly pay their bills online. (I’m a creaky crow, still leery of conducting any financial business via the Internet; it’s inescapable, of course, if you want to make purchases online, but paying bills or making banking transactions is just too big a leap for me, perhaps foolishly fearing a giant hack job will wipe out my account.)

My own handwriting is so wretched—I received a “D” in fourth grade in the subject, which vexed my mom terrifically, lecturing that poor marks in even inconsequential courses didn’t bode well for eventual college applications—that perhaps a bunch of my letters over the years have wound up in Utah. Sometimes I get checks back from companies—Verizon (of course), BG&E, Amex, Bank of America and others—which are deemed illegible, which is pain not only for having to write another check, but for the penalties sometimes levied because of the time interval. I can often call and get the extra charge erased, but it takes a lot of schmoozing—if you can actually reach a real human being—and often isn’t worth the trouble.

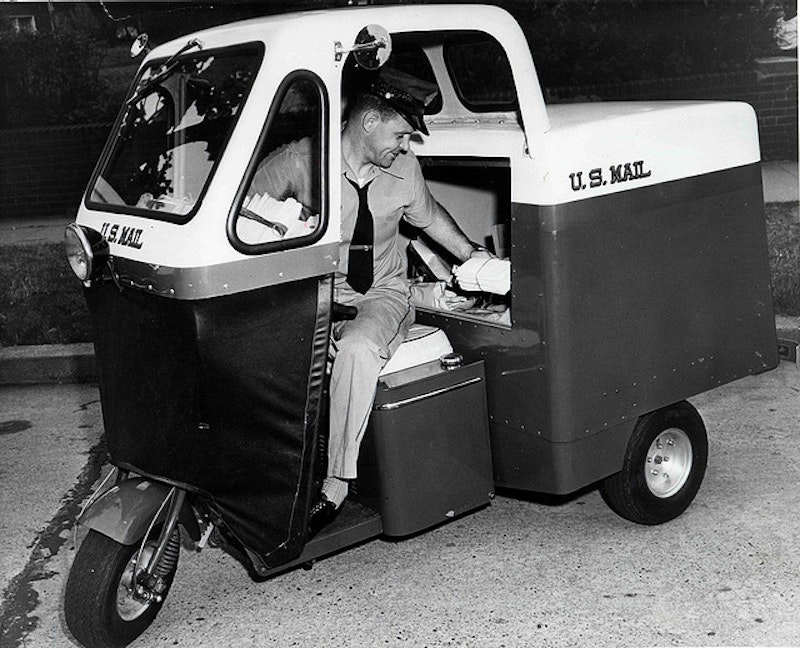

When I was a kid, maybe up to the age of nine or so, when asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, the reply was always, “a mailman.” It wasn’t such a leap, really, since our family received a huge volume of mail—largely because of my mother’s skill at winning contests sponsored by the likes of Dr. Pepper and Kodak (and phased out in the late 1960s in favor of less costly sweepstakes), but also a slew of magazines and personal correspondence, since all of us were inveterate letter-writers. One summer, I spent a lot of time on a mass mailing to various elected officials, with a personal note to each man—women officeholders were almost non-existent then—saying I was an aspiring politician and collector of campaign memorabilia. Our mailman, John, a great guy, greeted me with a smile upon seeing me at the bottom of our hill waiting for the day’s delivery, saying, “You’re wearing me out, Rusty!”

Over the past two decades, as the USPS has wallowed in red ink, fiscal conservatives have periodically called for privatization of mail service—perhaps to FedEx or UPS—and, predictably, are demonized by liberals who still believe unions are the backbone of the country (as well as a reliable vote and cash source for the Democratic Party). Just two months ago, The Orange Country Register ran an editorial pleading for privatization, making the valid point that taxpayers are picking up the burden for the massive USPS losses.

Normally, I’d side with the privatization champions, but really, in today’s electronic world, what company would undertake such a risky proposition? It’s more likely that the USPS will slowly wind down, reducing service to three days a week, raising the cost of doing business by the now-odious phrase “snail mail,” and slashing its workforce. “Going postal” will become a forgotten colloquialism. Mailmen, once a fixture in neighborhoods, sort of like the Good Humor guys, will be nearly invisible, and slip into the Saturday Evening Post category of Lost America.