Marcel Duchamp proclaimed that something becomes art when an artist says it’s art. This would make for a simple theory of art, and easily applicable. We can remember when Duchamp utilized this verdictive process to make a urinal become art. Yet this story would’ve vanished had others not recognized Duchamp’s pronouncement. Therein lies a decisive criticism of this belief about art. People who aren’t recognized as artists can’t declare their work to be art in this system. And there’s one group in particular ignored by the customs of artistic practice: incarcerated artists.

Stories about art-making in prison have become legendary and notorious. Lead Belly is said to have sung his way out of prison. Whether or not that’s true, the current situation is bleak. A recent book by Nicole Fleetwood, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, details the practices, products, and struggles of incarcerated artists. Trying to define “artist” is slippery; rather, I explain that incarcerated persons exemplify common characteristics of being an artist—education, practice, and community. In particular, I mostly refer to the Fairton Collective, which consisted of Gilberto Rivera, Jesse Krimes, and Jared Owens.

When it comes to the more traditional fine arts of painting and sculpture, there’s some prerequisite of education. From learning how to mix paints to get certain colors or how to carve in stone, these processes require learning, whether formal training for a degree or a mentorship. Incarcerated persons occasionally have access to formal educational programs, but often they rely on learning from each other. Fleetwood describes how Gilberto Rivera was moved from prison to prison to supposedly prevent him from developing gang associations. These regular moves may be awful for some, but Rivera took advantage to learn from artists at each location. Beyond learning the regular artistic processes, incarcerated persons have to learn skills that are only needed in prison, where materials and space are not always accessible or allowed. For example, artists have to learn how to acquire materials and use whatever materials they can find. In an effort (with great risk) to stretch larger canvases for his abstract paintings, Jared Owens snuck a large wooden plank into his area. He recalls that the three-yard walk was nerve-wracking; getting caught could’ve led to solitary confinement or an extended sentence. Great risk and limitation force them to learn (through mentors or trial-and-error) new methods or materials for making, which they develop and perfect.

Artists hone their skills through years of practice. Applying education to practicing their techniques over and over again is an important aspect to developing or shaping artistic instincts and habits. Incarcerated artists have to practice their craft as well, but with stringent limitations. Fear of having work confiscated causes many to work at night as if they were hatching an escape plan. Some materials are scarce or even inadmissible, so these artists need to practice acquiring and making certain colors—some colors are prohibited because of their chemicals and metals, such as many reds that contain cadmium. Jesse Krimes made a gigantic work (15 by 40 feet) on prison sheets called Apokaluptein 16389067. He not only had to acquire the prison sheets, but had to develop and practice a system for creating the larger work that he’d never see until released from prison.

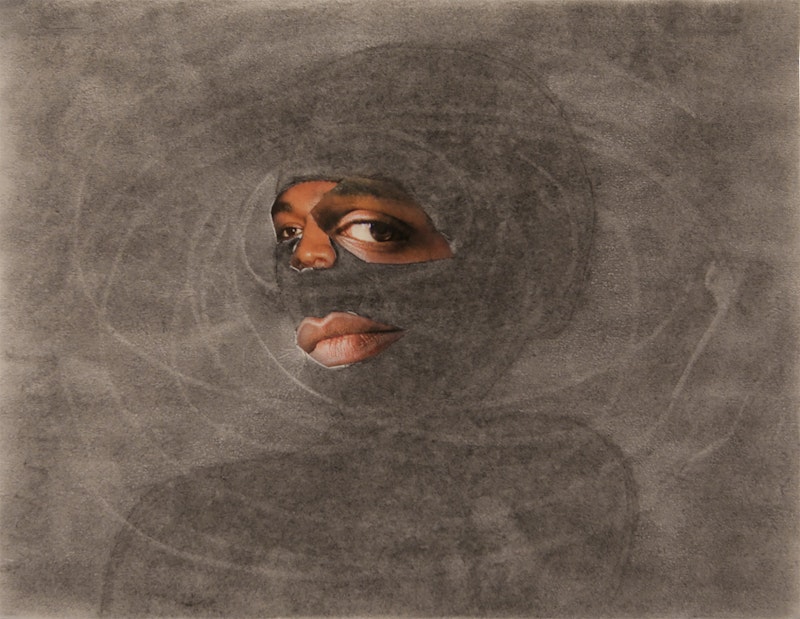

Making art can be isolating, and this is magnified in prison. Incarcerated persons still manage to carve out a community of artists and appreciators. Since cameras aren’t allowed in prisons, portrait artists, for example, are in high demand to create images of people to send to their families and to have in the own cells. Incarcerated artists gain the respect of other people in the prison. Art helps build and strengthen community between incarcerated persons and non-incarcerated family and friends. The Fairton Collective consisted of three men, and they’d have lengthy discussions about politics, philosophy, and art, which would fuel their art-making. Their studio space allowed them a break from the normal prison life, and gave them a small community in which to develop their artistic practices and vision. Incarcerated artists form communities for their art, but also for their survival as their creative work helps them cope with the severity of prison life.

One might wonder why these people make art in the first place. At any moment, their artwork and supplies could be confiscated, especially contraband; and they risk solitary confinement or even extended prison sentences. They can’t always sell their work for much money or gain some recognition, though it should be noted that selling prison art can be lucrative for the institution with some money going to the artist. For those artists that manage to get their work outside the prison walls, some don’t want to sell it. This drive to create art in prison illustrates convincingly that art and beauty are not merely added to an already good life; they’re more fundamental than that. Whatever other motivation incarcerated artists may have, making (and appreciating) art helps people to flourish. As a related illustration, Primo Levi relays a story from his incarceration in Auschwitz. He talks about a time where he tried to remember some lines from Dante to share with his friend. Art has a transformative and transcendent power, which we want to share with others. In a space largely deprived of aesthetic features—gray walls, drab jumpsuits—art can stand out against such a backdrop as a small signal of hope.

Michael Spicher is an educator and researcher in Boston and runs Aesthetics Research Lab, follow him on Twitter: @MRSpicher