“He was thinking in the moment,” announced a talking head who looked about 30, like he was a camp counselor. “That’s how he seems to do things,” the youth said. He meant the President (so to speak), Mr. Spontaneous. The 2016 election faced off the last pair of candidates born in the prime baby boom years. The result: a president who’s the quintessence of the baby boom mentality. Donald Trump, born 1946, is rock ‘n’ roll. He’s TV. He’s action and the immediate. Never mind what comes before or after. He slices through to the Now. He’s so Now that he can’t see forward or back. Hence his telling the nice Russian man about the intel we have on ISIS. He was in the moment.

A generation ago, journalists played with the idea of a rock ‘n’ roll politics or politician. Jerry Brown was considered such an article, and for good reason: he had a Dylanesque bend to his personality and played with his audience, otherwise known as the voting public. But no other rock ‘n’ roll politicians showed up. When Bill Clinton took office, the first baby boom president proved novel for his touchy-feeliness—not in the sex sense (since John Kennedy, a pre-boomer, had broken that ground), but in the term’s afternoon-talk-show sense. Touchy-feely shares with rock a dwelling on emotion; still, it isn’t rock ‘n’ roll. A rock ‘n’ roll politics would be a politics of excitement, of jolting people. The boomers have been more interested in calculating audience reaction and its management. Hence the presidents and would-be presidents who prowl about with hand mikes, taking audience questions and answering with what the focus group said. In this way, a generation’s aspirational self-view (the rock ‘n’ roll generation) gave way to reality, and reality was mainly a matter of doing the coursework and looking at the research and showing up at the office.

Until now. The baby boomers, those badasses who won’t take reality’s shit, are living up to their old boast. We have our rock ‘n’ roll president. Of course, by this point nobody cares. Trump’s blatancy matters to people, but nobody recollects the rock side of it. Nobody notices the final, long-delayed emergence of the old dream. The PAs play old Rolling Stones at Trump rallies, and all that gets through is the tedium of that prolonged high note hit by the women’s chorus in that one song, the one that goes on forever. The keening hangs like jet noise while a Trump supporter answers questions from a reporter’s microphone.

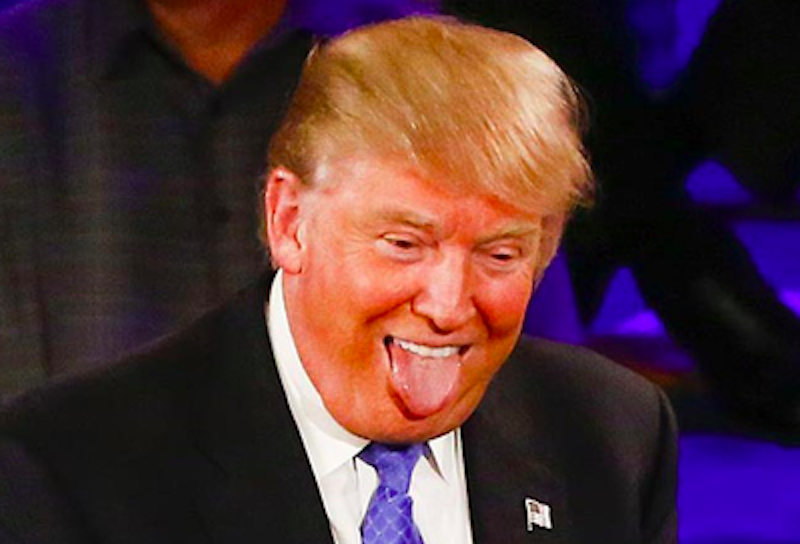

Then the star enters and the fans erupt. But it’s just Trump. That on-stage dynamo and monstrosity, that figure who’s riveting or you can’t watch him at all, is the same foolish old man who’s been boring us with his confusion for two years now. He can’t be ignored, yet he’s easy not to notice. Like an AC/DC riff heard while on line at the pharmacy, he’s noise.

DVD corner. Why did Robert De Niro and the girl (Anne Hathaway) have to lie on the bed together? Fathers and daughters don’t go for that, I think. Why does Hathaway’s fellow look like—how to say—Kirk Douglas picked out his accoutrements with an eye to keeping Kirk Douglas from feeling threatened? The young fellow’s face is half-Muppet, and he bleats like a kazoo. He’s the one who fucks Hathaway, but the deed doesn’t count because he’s such a null. Whatever counts about a man going to bed with a woman gets wafted over to the scene with De Niro and Hathaway, who aren’t in bed but on a bed, and he’s got his suit on. They’re not really doing anything. They’re just stationed to receive the wafting from her and her husband’s sex life. Docking is achieved, and we have a refracted sex scene. The baby boomers, typically, have found a way to sex up fatherliness.

The Intern (written and directed by Nancy Meyers, born 1949) is part of the last long march of baby boomer cultural product. We see what boomers make of old age. With The Intern, boomers work a cultural dodge, a switch. They give themselves the Greatest Generation treatment, meaning they act like they survived a depression and fought a world war. Just carrying a briefcase makes De Niro’s character a hero. He showed up and did his job, and he wore a tie. The newcomers, these Millennials, mainly work for a living, so they’re doing jobs. But they’re not wearing ties. There, you see, is the difference. This touch seems very baby boomerish, to those of us who remember that generation’s historical profile. Boomers placed weight on signifiers. It had to be long hair, not short. That particular preference also reflected that they were rebels. Now, shuffling off to the old folks home, the boomers want respect because of their brief cases.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3