“Are you a politician, Roscoe?”

“I refuse to answer on grounds that it might degrade or incriminate me.”

—From Roscoe, by William Kennedy

This is a story my father told me, some of which was confirmed by my mother. I’d reached an age sufficient that he felt comfortable with us both surrounding the contents of a bottle containing the waters of life. He spoke of a time when he was working as office manager of an alarm company near Albany, New York. My father was a craftsman: he occasionally went out on jobs just to keep his hand in.

If memory serves, he went to a small suburban town to the house of one William Kennedy. The name meant nothing to my father, who was extremely intelligent and well read in a narrow body of classic literature but avoided the modern novel.

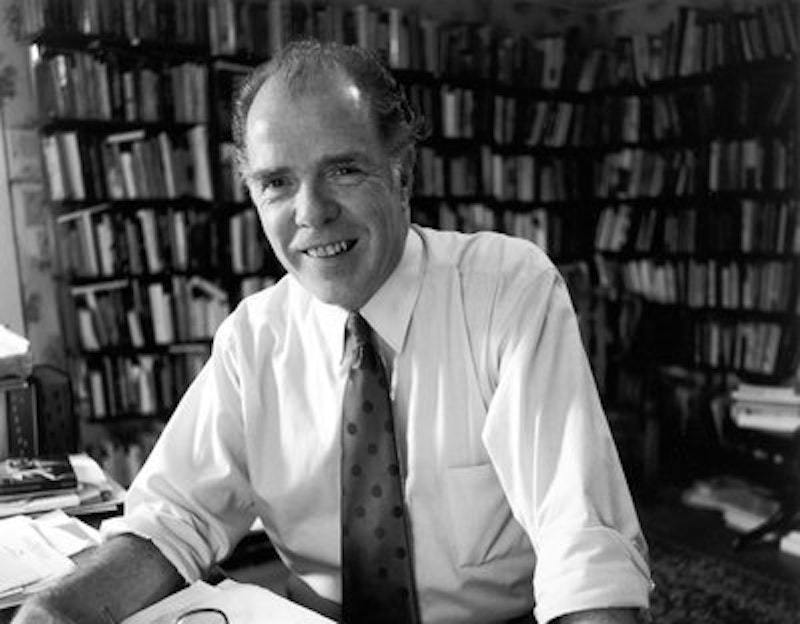

Kennedy, author of Ironweed, among other books, greeted my father at the door. After the usual polite exchanges, each man took a closer look at the other. Kennedy asked, “Didn’t you run the National Auto Store on Central Avenue?” My father replied, “Yes. Didn’t you work for the Albany Times-Union?”

My father explained that, though only knowing Kennedy as a customer, he had liked the man, because he came into the store every week to pay his account on time. He recalled, “He dressed like a reporter, with a fedora tilted on his head.”

Anyway, they went through the house, my father offered a careful estimate of the price of installing and maintaining a security system, and they shook hands on it. Then, my father told me, Kennedy offered him a drink. They went into the kitchen, sat down at the table, and began talking of all the personalities they’d each known. As a journalist, I’m sure Kennedy knew everybody. And as the manager of one of the city’s major automotive repair services, many people came to see my father.

Several hours passed. The contents of the bottle may have visibly diminished. My father asked Kennedy for the use of his telephone, called my mother, and asked her to pick him up as he didn’t feel up to driving home. She did. She drove him back the next morning when my father, perhaps the worse for wear, picked up the alarm company’s truck. His employer, having been known to surround a glass or two in his time, did not complain.

I don’t live in my past but I often think about it. So when this anecdote popped back into mind, I took one of Kennedy’s novels down from the shelf.

In Roscoe, Kennedy continued working the vein prospected by two minor classics, William Riordan’s Plunkett of Tammany Hall and Edwin O’Brien’s The Last Hurrah. The seventh Kennedy novel set in the author’s hometown of Albany, New York is elegantly crafted, often uproariously funny, and betrays both a profound understanding of human frailty born of original sin and the sure knowledge that man born of woman is doomed to sorrow.

His characters, of course, enjoy themselves as best they can, usually at each other’s expense. Thus, one of Roscoe’s numerous memorable minor characters, Mac, one of the cops who assassinated Legs Diamond when the racketeer failed to understand that the Albany County Democratic machine was far more powerful than the mob, reflects on the stabbing murder of an informer: “Robbed and stabbed, and he dies naked, broke, full of holes, and covered with blood. I like it.”

Later, just before a fixed cockfight between birds owned by two brothers and party bosses, Patsy and Bindy McCall, Bindy introduces Roscoe to his fighting cock.

“This is the Swiggler,” says Bindy. “You ever been swiggled?”

“Not by a chicken,” answers Roscoe.

Kennedy closes the book with his author’s note, expressing his gratitude to numerous persons, living and dead, whose stories and knowledge helped him to form his work. Kennedy may have begun with facts. His novel is full of historical figures, from FDR and Al Smith to Herbert H. Lehman to John McCooey and John Curry, the one-time Democratic bosses of Brooklyn and Manhattan. Of course, in the novel, these figures are all invented characters, just like the other invented characters of whom we’ve never heard.

Yet, having been born and raised within 10 miles of the city of Albany, I know many of his invented characters are closely modeled on once-living persons. A knowing Albanian might read a William Kennedy novel merely to pick out the old pols, pimps, and hangers-on. This would be vulgar and more than a bit of a mistake. I admit having done this.

Thus, in reflecting on Kennedy’s fictional political boss, Patsy McCall, I think of the great Dan O’Connell, who ruled Albany’s Democratic Party and thus Albany for over half a century. He had a certain knack for massaging election results. Mario Cuomo once told a story about Dan being marooned on a desert island with another fellow, and only one coconut between them. They voted on who should eat it, and Dan won by 110 to 1.

Happily, for the rest of us who may not know Kennedy’s Albany, the “City of Political Wizards, Fearless Ethnics, Spectacular Aristocrats, Splendid Nobodies, and Underrated Scoundrels,” the book stands on its own. He’s among the handful of important contemporary novelists trained in the old school of journalism: the discipline of publishing facts with an economy of words to a daily deadline. And it’s honorable praise to note that even his lesser books are exquisitely finished and all have integrity, for they are the work of an honest man.

Roscoe is a novel set in the summer and fall of 1945, in which Roscoe Conway, lawyer, orator, and Democratic political operative, attempts to escape from the life he has made. This does not hint at the amazing tangle of subplots, whether fixing elections, child custody suits, suicides, payoffs, assaults, brothel raids, cockfighting, murder, sibling rivalry, or gambling rings. Yet, the narrative is not confusing. Kennedy’s art captures the essence of life—just one damned thing after another, with nothing ever finally resolved but merely overcome for the moment.

I found his author’s note poignant for personal reasons. One of his sources was the first politician to give me an interview, when I was writing for the Shaker High School Bison in 1971. Erastus Corning 2d (he preferred the Arabic to the Roman numeral) was elected mayor of Albany 11 times before his death in May 1983. No American mayor has served longer. As Kennedy notes in O Albany!, his offbeat history of the city, Corning held power “longer than Trujillo, Franco, Peron, Batista, Somoza, Napoleon, Hitler, Mao, Catherine the Great, Peter the Great, Henry VIII, Ferdinand and Isabella, Ethelred II, and… Augustus Caesar.” Even at 16, I found the urbane man across the table from me both a great gentleman and one of the toughest guys I would ever meet. Fifty years have passed, and I’m still right on both counts.

Corning’s unusual first name (after 40 years in office, some believed his real first name was “Mayor”) is a Latinized version of the Greek erastos, meaning beloved. He was brilliant (Yale ’32, Phi Beta Kappa, with a dual major in history and English literature), precocious (Assemblyman at 26, State Senator at 27, Mayor at 32), and hardworking (he worked a 60-hour week). He inherited wealth and made more through his political connections. His insurance agency, Albany Associates, wrote 90 percent of Albany County’s insurance, meaning some $1.5 million in annual premiums; as he was a city, not a county official, the law found no conflict of interest.

At the height of his power, his authority over the city and the county of Albany was absolute. A local newscaster once told him on camera, “…you hold such power that if you told the Common Council to meet in pink lingerie, they would.” Corning replied, “I think you go too far. Blue lingerie, perhaps. But pink is too much.”

Kennedy has written elsewhere that Corning was uninterested in the truth. I disagree. Corning’s capacity for deceit was merely a weapon in his intellectual arsenal. Like Talleyrand (who would have found him a kindred spirit), Corning believed language existed to conceal truth.

Most people who rely on lies to get through the day eventually lose touch with truth. Corning never did. After all, you don’t have to believe your own lies. When lucidity was required, his gifts for written and oral expression made him utterly, often brilliantly, clear. The same gifts let him obscure, obfuscate, and evade. At the height of his power, he played the press and the people like grand pianos.

Even Kennedy was not exempt. The story goes that some 60 years ago, as a working reporter, during a press conference, Kennedy told Corning that a recent visitor had said the abandoned buildings in Albany made it look like a ghost town or a demolition project, and asked for his response. The Mayor replied that a well-known television commentator had come to Albany and seen all the construction and said it was one of the most vital, growing cities in the Northeast. After the press conference, Kennedy asked the Mayor, “Who was the well-known television commentator?” And the Mayor asked, “Who was the recent visitor?”

I imagine the Mayor’s sparkling joy as he declaimed his most famous epigram, “Honesty is no substitute for experience.” How could any intelligent reporter with a sense of humor resist someone so brazen, magnificently audacious, and in command of his wit that, when asked his favorite color, replied, “Plaid.”

In Roscoe, Kennedy creates a character, Alexander Fitzgibbon, whose personal and political careers are nearly identical with Corning’s. The resemblances are purely intentional. So are the resemblances between numerous persons and characters. Dan O’Connell seized power over the Democratic Party and then over the city and the county of Albany with the help of his brothers between 1919 and 1921. So had Patsy McCall, the crude, violent, corrupt party boss in Kennedy’s novel, who has been “in politics since he was old enough to deface Republican ballots.” But to suggest that Kennedy has merely copied the facts and changed the names is wrongheaded. In fact, Fitzgibbon and McCall, despite Kennedy’s artistry, are simply not as tough or as coarse as their models. It would be difficult for them to be. No one would believe it.

At its heart, the novel lives in a corrupt world. Thus, Kennedy quotes Roscoe’s dead father, Felix Conway, a disgraced ex-mayor, in a passage, “Felix Declares His Principles to Roscoe”: Never buy anything that you can rent forever.

This has particular resonance in Albany County: a wonderful scandal of my youth dealt with a Democratic loyalist contractor who leased a Jeep to the city for $988 a month. He had paid $800 for it used.

Also: “Give your friends jobs, but at a price and make new friends every day.” This may explain why, for example, the Empire State Building employed 60 janitors for 102 floors while the Albany County Courthouse employed 72 for six. Every year, the county employees contributed three percent of their salary to the organization. You didn’t need to shake down the banks for campaign funds if your own people provided the loaves and fishes.

And: “People say voting the dead is immoral, but what the hell, if they were alive they’d all be Democrats. Just because they're dead don’t mean they’re Republicans.” On a similar note, I recall reading of a state investigation in the 1940s into the 78 voters registered out of a single Albany boarding house. The investigator found only 22 cots. The landlord explained that the voters slept in eight-hour shifts. This meant, of course, that the other 12 guys had to sleep standing up.

Finally, Kennedy’s pols, though drawn with affection, are never twinkling benignities out of Frank Capra. This is as it should be: machine politicians liked to think of themselves as means of rough justice, bringing coal and food to the poor. Albany’s machine bosses were tough, ruthless men for whom democracy was always spelled with a capital D and politics merely another way of making a living.

Stendhal used the word crystallization to define the process by which the creative mind transforms mere fact to fiction. The analogy was drawn from certain German salt mines, where one might leave behind a tree branch and on returning some years later, find it encrusted with salt crystals, like tiny diamonds. So Kennedy’s memories of a small American city were transformed by time and imagination into enduring art.