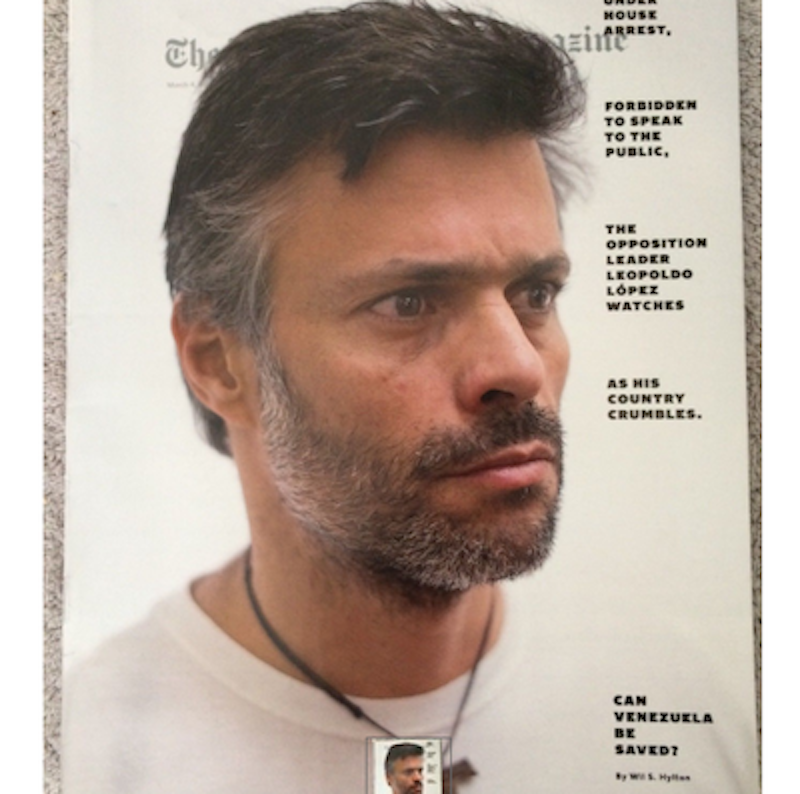

Last March, The New York Times Magazine ran a fawning, beatific profiles about Venezuelan opposition figure Leopoldo Lopez. The story was headlined, “Can Venezuela Be Saved?” If the country could be saved, the article made clear, Lopez was its only hope.

Right away readers knew they were dealing with a heroic, epic figure because the story opens by comparing Lopez to Martin Luther King. “He has become the most prominent political prisoner in Latin America, if not the world,” Wil Hylton wrote, in one of many dubious assertions. Lopez is hardly a household name and to the extent he is, it’s because the U.S. media has been writing PR for him for several decades.

Many world leaders love Lopez, Hylton writes, among them Angela Merkel, Emmanuel Macron and Justin Trudeau, and he’s “that rarest of political causes on which Barack Obama and Donald Trump are in agreement.” The boot polishing got worse from there; the story was illustrated with photographs that Lopez could use if he wants to put together a modeling portfolio. “On the spectrum of American politics,” we’re told, Lopez “would probably land in the progressive wing of the Democratic Party.” Just the sort of thing that would make denizens of New York’s Upper West Side—the Times’ core demographic—love him.

There was a follow up piece by Hylton a week later in the Times magazine (“Leopoldo López Speaks Out, and Venezuela’s Government Cracks Down”), a short item about the challenge of taking Lopez’s portrait for the story since he was under house arrest (rather easily solved it turns out; his sister visited his home and snapped the photographs) and two reverential The Daily podcasts during which Hylton and host Michael Barbaro marveled at Lopez’s saintliness. In one segment, Hylton interviews Lilian Tintori, Lopez’s wife, and almost tearfully prods her to say that her husband is “married to Venezuela.”

This is pure garbage. Lopez has suffered at the hands of the Venezuelan government, but no regime on the planet would have tolerated his activities given that he has been trying, with U.S. support, to overthrow the government for more than a decade. Given the violence routinely inflicted on dissidents and poor people in much of Latin America, Lopez’s “plight” is rather unremarkable and indeed quite comfortable.

He’s "surrounded all day and night by the Venezuelan secret police,” writes Hylton. Why yes, he is, while serving house arrest at his lavish family home in the suburbs of Caracas.

Lopez is a fraud: read this brilliant profile of him in Foreign Policy by Roberto Lovato—an extraordinarily rare critical look—to know how badly Hylton was played, and how he collaborated with his subject, the Venezuelan opposition and the Trump administration, the latest U.S. regime that is seeking to overthrow the leftist government.

Now, with President Trump actively pursuing the overthrow of President Nicolas Maduro—and replacing him with Lopez’s protégé, Juan Guaido, recognized last week by the U.S. as Venezuela’s “interim leader”—the Times story looks like a small piece in a propaganda time war against Venezuela dating to 1999. That’s the year Hugo Chavez was elected president and he was re-elected, always in free and fair balloting, three times. Maduro, his last vice president, won a special election in 2013 after Chavez died, by less than one percent of the vote. He was reelected in a landslide last May. The election was boycotted by most of the opposition, and the United States and many other governments refused to recognize the results.

Since 1999, successive U.S. administrations have sought regime change in Venezuela, among them that of George W. Bush, which supported an unpopular coup attempt in 2002. But none have been more aggressive than Trump, who last fall “held secret meetings with rebellious military officers from Venezuela to discuss their plans to overthrow President Maduro,” the Times reported.

(Curiously, American oil companies active in Venezuela, such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, have not said much publicly about Trump’s attempt to overthrow Maduro. Hopefully that’s because they know -- as the president should -- that war is bad for business, but they have a fortune at stake and they may decide they’ll make more with Maduro done. One expects that the voice of these oil companies will have a large and possibly decisive impact on what Trump ends up doing. The other decisive factor will be if the Trump administration can convince enough disgruntled military officials to betray their country and remove Maduro. There is, as I note below, plenty to be disgruntled about if you are an average Venezuelan but selling out your sovereignty to a foreign power can never be justified, no matter how much Yankee Gold you are offered.)

Hylton’s piece is typical of the way the U.S. media has followed the government line. It's reminiscent of the sycophantic coverage in the run up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, when the press corps collectively served as shoeshine boy for Ahmed Cahaba, the corrupt, despised CIA-funded Iraqi “opposition leader.”

Like a lot of the coverage, Hylton’s story reads like it was scripted by a lobbyist for the Venezuelan opposition—and it turns out it was. The lobbyist is Rob Gluck, managing director of High Lantern Group. The contract, which has since been terminated, was for up to $15,000 a month and was signed by Tintori, Lopez’s wife.

Imagine if the Times had allowed a writer to profile Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman—lovingly fellated here by the columnist Thomas Friedman, with or without lobbyist guidance is not clear—in a story at least partly arranged by a PR hack for the Saudi regime paid for by one of the crown prince’s wives? Or if Pravda had profiled Joseph Stalin on the basis of information provided by one of the Soviet leader’s paid propagandists? It wouldn’t look good, would it?

More on Gluck and Hylton later.

I detest the leadership of the Venezuelan opposition and admire Chavez, but my opinions are well-informed. I first traveled to Venezuela in 1993, when Chavez was in prison for leading coup against the famously crooked, U.S. media- and government-backed government of Carlos Andres Perez.

CAP, as he was known, had ordered out Army troops to shoot demonstrators—hundreds or even thousands were killed, the exact number was never determined—against an IMF austerity plan. CAP later died in disgrace in Miami, where he lived lavishly in exile, when he wasn’t doing the same in New York and Santo Domingo. His wife and his mistress had an angry, public feud about where to bury his remains and divide the money he had stolen from the Venezuelan people.

I traveled to Caracas again in 2004, when a U.S.-funded opposition campaign to recall Chavez spectacularly crashed and burned. I then worked for The Los Angeles Times and the government, through a small leftist PR shop where a friend of mine worked, offered me an interview with Chavez on the eve of the vote. The PR shop knew I was sympathetic to Chavez—I wrote about him in 1993 for The Nation—and that I was the only person in the U.S. mainstream media who might write anything favorable about him.

But the Times, whose top editor was Dean Baquet, now executive editor of The New York Times, didn’t trust me so sent along one of its Latin American bureau chiefs, Carol J. Williams, as my babysitter. It was a nightmare working with Williams, who was completely anti-Chavez. When the Times’ local photographer told her he intended to vote against the recall, she tried to pressure him to work early on the day so he wouldn’t be able to cast a ballot.

Williams and I couldn’t stand each other and on Election Day we split up and wrote separate stories. Williams, who talked to her friends in the elite and other U.S. reporters, wrote a story for Page 1 that strongly suggested Chavez would be routed, saying that his “power base is estimated by pollsters to be about 30 percent.” I spent the day in the barrios and wrote a piece, “Support for Chavez Unwavering in Slums of Venezuelan Capital,” that predicted Chavez would defeat the recall since he was loved by the poor majority.

The recall was crushed with 58 percent of the population opposing it and my editor on the Times’ Washington investigative unit said I’d saved the newspaper from humiliation. But for most of the Times’ top editors, I was the untrustworthy reporter and Williams—who spent most of her time in Venezuela hanging out with Western reporters who hated Chavez and who all wrote nearly identical stories based on their echo chamber conversations—was the seasoned, neutral old pro.

Incidentally, even Hylton acknowledged that Chavez had been “wildly popular” with the poor. “During his tenure, unemployment fell by half, the gross domestic product more than doubled, infant mortality dropped by almost a third and the poverty rate was nearly halved,” he wrote. “Under his watch, income inequality dropped to one of the lowest levels in the Western Hemisphere.” But that was it in terms of anything positive. “Chávez also possessed an autocratic impulse,” Hylton wrote. “Over the course of 14 years in office, he dismantled the country’s democratic institutions one by one.”

One could just as easily argue—especially now that the government might be overthrown—that Chavez should’ve been far harsher towards an opposition that was on the payroll of the United States and determined to subvert and overthrow his elected government. Instead, he and Maduro allowed the opposition to stage huge protests and control much of the media.

If Chilean President Salvador Allende had been more ruthless, Augusto Pinochet would never have taken power on September 11, 1973 and probably would’ve died in prison. And, relatedly, when news outlets and the U.S. government endlessly call Maduro a dictator, be skeptical.

That said, I have a lot of problems with Maduro. I’m not sure if it was his intention or whether he’s been pushed towards authoritarianism by U.S. pressure—in addition to support for the opposition, economic sanctions that are bleeding the country and starving its people—but I oppose many of his policies and actions.

I also feel badly for the Venezuelan people. Whether because of U.S. policies or Maduro’s, no doubt both, they’re suffering. “Venezuelans living in the US, and many on Twitter, are mostly from wealthier fams,” Boots Riley wrote on Twitter on January 23. “They aren’t SIMPLY Venezuelan. They have class interests that aren’t the same as poor Venezuelans.”

That’s not true. I lived in Miami for much of 2017 and part of 2018 and spoke with hundreds of Venezuelans from all over the class spectrum. They left because they were hungry and had few options. Furthermore, there are multiple accusations of corruption against Maduro and his family, and a lot of them are credible.

I still believe much of the opposition sucks and it’s worse than the government. If they forcibly take power they’ll deploy violence against their opponents, with no outrage from the U.S. media or government, far more routinely and frequently. I also can’t stand U.S. media and government hypocrisy about Latin America. Far worse violence and poverty is common across the region. Brazil has a fascist leader who was elected after the local elite dummied up the bogus “impeachment” of an elected leftist. Violence against the poor, dressed up as crime fighting, is out of control.

Dictatorial and “democratic” governments in Colombia have spent decades, again with little protest from the U.S. government or media, slaughtering poor people and targeting leftist activists. It’s sort of like Richard Nixon’s failed attempt to pave Southeast Asia with dead people in the 1960s and 70s and pretend he supported democracy while backing thugs.

I’d also note that Bill and Hillary Clinton, in public and private life, kissed the ass of the worst Colombian killers in hopes of making money, some of it for the Clinton Foundation. One of the Clinton Foundation’s biggest donors allegedly ran a concentration camp for workers in Colombia.)

Finally, let me state the obvious: I oppose U.S. intervention in Venezuela. I believe Trump is being stupidly led into war by his most hawkish advisors and the ghastly Florida Sen. Marco Rubio.

Anyway, back to Hylton and Gluck.

High Lantern Group, which promoted Lopez in the media, ran his website and handled at least some of his social media, is a little known but powerful D.C. firm. The contract promised it would turn Lopez into South America's Nelson Mandela and was worth as much as $15,000 per month.

One has to wonder where all that money came from. Lopez's mother paid the PR firm, one very well-placed source told me. The contract, no longer in effect, was signed in August 2017. It calls for the PR firm to peddle Lopez in the media and brags that High Lantern has extensive ties to reporters.

The Times magazine and Hylton pimped Lopez in March 2018, seven months after the contract was signed. The story says Hylton first met Lopez through an unnamed and mysterious "intermediary." Might the intermediary have been Gluck? And what did High Lantern do for Lopez and how much contact did it and Gluck have with Hylton?

I emailed Gluck some time back to ask about all of this. He wrote back:

We're not working with Leo in a formal way at the moment and haven't since the beginning of the year. He is a college classmate of mine [at Kenyon] and close friend—and I've tried to do what I can over the years to provide support to him in what has been an egregious, and at times dire, situation.

I later spoke to Gluck on the phone and he was reluctant to say much. He did say he wasn’t sure if he was the "intermediary" mentioned in the Times magazine profile, but said he may have been and that Hylton reached out to him through Lopez's lawyer.

I emailed Hylton late last week for comment. I wrote:

I’m on deadline now, writing about your story for NYT mag on Leopoldo Lopez and how much help you got from Rob Gluck, who I interviewed around the last time I communicated with you.

—How much did Gluck help you? He is a PR hack and lobbyist for Lopez, and had a contract with Lopez's wife to get positive media about him. Do you see that as a conflict since you wrote so much fawning copy about Lopez and his wife?

—Who was the "intermediary" who introduced you to Lopez?

—Your profile was a blowjob, to put it mildly. Any regrets?

I haven’t heard back from him. If I do, I’ll happily update this story.

Much of U.S. coverage reads like it was dictated by the State Department and lobbyists for the Venezuelan opposition. On January 24, CNN International had on Lilian Tintori to talk about “20 years of dictatorship” in Venezuela.” (H/t Sam Husseini.)

“There are millions of people in Venezuela who elected and support the government that Trump is trying to overthrow, but they are made invisible by an American corporate media that has salivated over the right wing takeover of Venezuela for decades,” Rania Khalek had aptly noted on Twitter the day before.

As noted, I have problems with Maduro, but at times you take sides and right now there are only two. I’m for him and against the U.S. and the rancid old oligarchy, as Chavez called the opposition, which is masquerading as a democratic force only with the help of Hylton and other media accomplices.