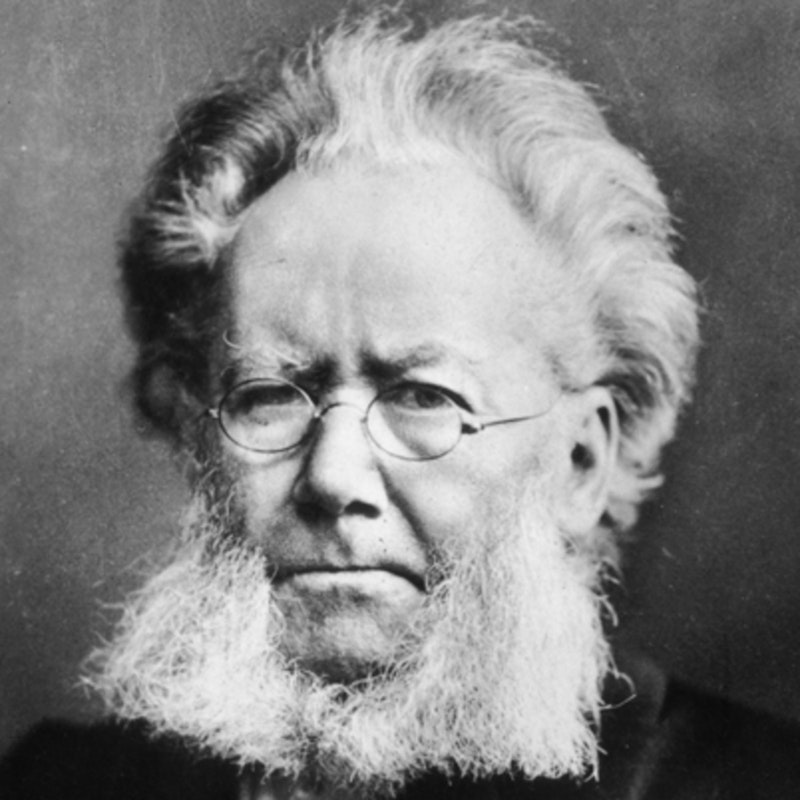

Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People has seen a resurgence within the past year, as President Trump has unknowingly referenced its title to disparage the press. Our political climate has amplified the most common interpretation, shared among American critics, journalists, and dramaturgists, of the 1883 play—that it’s about how a fascist government censors the truth and conditions its citizens to believe in a false reality. If the President was familiar the Norwegian playwright, he might skip the literary allusion, considering that the local government was working with the press, not against it, in order to subdue the dissenting protagonist.

Dr. Stockmann lives and works in an unnamed Norwegian village where he tries to warn the townspeople that the water’s poisoned. The mayor, who’s his older brother Peter, can’t let this information leak because it would compromise the success of the local spa, which is the village’s main tourist attraction and source of income. Despite being framed by his brother and the press as an enemy to society, the doctor, in his valiant endeavor towards transparency, stands tall as “a man of intense, personal courage”—that’s how he’s described in the trailer for the 1978 film adaptation, starring Steve McQueen as Stockmann. If only good and evil were as conveniently delineated in the original An Enemy of the People. Ibsen’s play is much trickier with its politics than its most common interpretation, which undergirds the film, would like the viewer/reader to think.

Stockmann is not exceptional in the scheme of Ibsen’s men. Helmer in A Doll’s House is no less condescending and self-absorbed than later men like the titular character in John Gabriel Borkman or Rubek in When We Dead Awaken—and all three are so despicable that, to varying degrees, each of their wives abandons them. Although his wife and kids remain by his side, Stockmann isn’t an anomaly for the playwright. Perhaps An Enemy of the People isn’t quite about how fascism silences its liberal dissenters, as the common interpretation goes, but how insular, scabby men such as Stockmann have the capacity to screw everything up and play an unintentional role in enabling fascism to prosper. The shared corruption between the mayor and the press is infuriating to see unravel over the course of the plot’s five acts, but it’s also cathartic to witness a snide, performative activist getting his comeuppance.

Prior to the timeframe of the play, Stockmann, who’d been serving as the spa’s “medical officer,” was contributing pieces to the local newspaper about the health benefits of going to spas such as the one he works at (the 18th century equivalent of sponsored content). But he learned that toxic waste was festering in the soil and infecting the water pipes, so he wrote a letter to the Spa Institute’s board warning them not to build there. Peeved that the board members didn’t believe him and planned to build there regardless, he took a water sample from the spa and sent it to a chemist at the nearby university, from which he receives a letter back during Act One: Yes, the water was indeed contaminated. “[B]ack then nobody wanted to listen to me,” Stockmann boasts to his household about the board-members. “Well, now I’ll launch a broadside at them, believe me.”

Based on his giddy reaction, Stockmann’s endeavor towards revealing the truth during the next four acts ends up reading like a drawn-out, petty Told-ya-so. Of course he already knew he was right without the scientific corroboration; he’d prewritten a report to send to the mayor, the chairman of the Spa Institute’s board. Looking for an envelope, he asks after the maid—”Oh, what the hell’s her name again?”—who goes out to deliver the report and chemist’s letter to his older brother. The first act closes with Dr. and Mrs. Stockmann joyously dancing around the house together, while the grave implications of his findings don’t seem to weigh on him or anyone else under his roof. What really matters is the fantastic opportunity being posed by this environmental calamity: Now he gets to lead a revolution!

Stockmann fantasizes about representing the citizens, though he’s never depicted interacting with them, other than in Act Four when he’s giving a speech and, evoking eugenics, deems the assembled collectively inferior due to their biological makeup. He’s insulated from the class of people he claims kinship with; he doesn’t even know the name of his own maid. He’s unable to place himself outside of the contexts with which he’s already familiar, which is why his conception of revolution doesn’t extend beyond continuing to write inflammatory articles in the newspaper. He thinks that once citizens read his article about the spa water being poisoned, they’re going to throw him “a parade, or a banquet,” or award him a lot of cash “for a token of honour.”

He displays a constant need to assert himself by bombarding the townspeople with his articles—a quality that is unsurprisingly integral to the centrist-liberal pundits of today. When Jonathan Alter haughtily blurts “Don’t Believe Critics, Education Reform Works,” or Jonathan “Scab” Chait and Mark Lilla glibly bemoan identity politics, they’re asserting themselves just like Stockmann. Here’s how you, the dumb and irrational, are wrong; and here’s how we, the sensible white guys, are right. They claim to be looking out for liberalism, yet their condescending attitudes end up bolstering dangerous trends in conservatism.

Stockmann’s personal activism is actually a front for his impulsiveness and obsession with garnering clout, and it’s these two qualities that ultimately lead to his undoing. As he plummets and can’t help pushing himself deeper down, his brother benefits. The doctor’s concluding line—“The strongest man in the world is he who stands most alone”—reveals that he’s a serious threat to community solidarity since he’s that unwilling to reflect upon himself, even after being faced with the consequences of his destructive, ungovernable arrogance. The play’s title mockingly deploys the epithet used by the mayor and his minions, but it also suggests that liberals can be bad guys, and maybe Stockmann truly was an enemy all along.