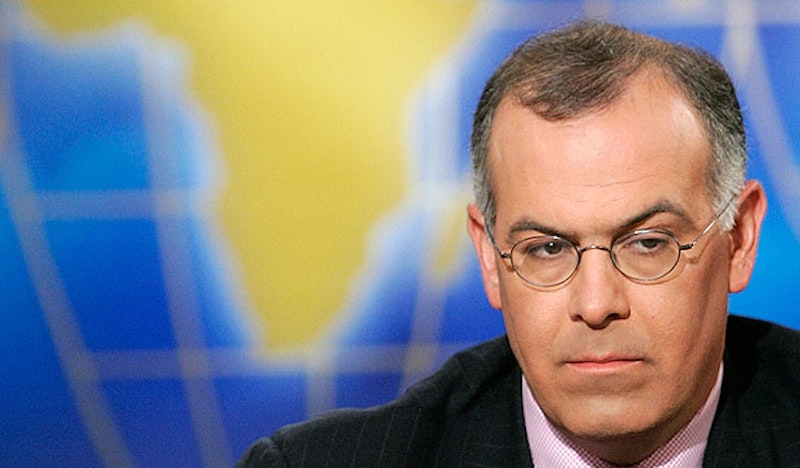

Somehow, in the deluge of hyperbolic praise for Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book Between the World and Me, David Brooks’ obligatory hot take isn’t the one that got me most steamed. I doubt anyone can top A.O. Scott’s ridiculous assertion that Between the World and Me is “essential, like water or air,” but if anyone can make you cringe, it’s Brooks. Naturally, he writes his response as a letter to Coates, just as the author’s book is addressed to his son. A very Brooksian move that sets you up for all the worst “All Lives Matter” and condescending nonsense about “black on black crime,” but surprisingly, Brooks has few qualms and little to quarrel with Coates. He concedes “maybe the right white response is just silence for a change,” and that Between the World and Me “filled [his] ears unforgettably.” I wonder what he would’ve said a year ago. In any case, the clueless clickbait hack takes issue with Coates’ “disturbing challenge of the American dream,” and the immediately proves the author’s point by proudly stating that his ancestors chose to emigrate to America, while Coates’ ancestors, bound in chains, had no choice.

Unable to wholesale reject Between the World and Me’s “excessive realism” (what?), Brooks claims that Coates distorts American history: “This country, like each person in it, is a mixture of glory and shame. There’s a Lincoln for every Jefferson Davis and a Harlem Children’s Zone for every K.K.K.—and usually vastly more than one. Violence is embedded in America, but it is not close to the totality of America.” At least not for a middle-aged white Boomer. Living in a segregated city like Baltimore, the split between worlds is impossible to ignore. The violence, white supremacy, and utter lack of care or sympathy from a corrupt city government that continues to funnel money into the Harbor while allowing West Baltimore to go weeks without water in the winter—that’s tangible, visceral. “Dreamers” are contained within the main arteries of Calvert, St. Paul, and Charles Sts. East and West Baltimore operate under different rules, neglected and ravaged every day. College students, tourists, and residents of the arteries are urged to stay within narrow safe zones, furthering the chasm between two worlds that are separated by single sidewalks.

Brooks goes on: “In your anger at the tone of innocence some people adopt to describe the American dream, you reject the dream itself as flimflam. But a dream sullied is not a lie. The American dream of equal opportunity, social mobility and ever more perfect democracy cherishes the future more than the past. It abandons old wrongs and transcends old sins for the sake of a better tomorrow.” Again, this is easy for someone like Brooks, but he’s never been randomly stopped and frisked, never had a family member killed by overzealous police, his neighborhood isn’t willfully starved of resources. For Coates, growing up in West Baltimore, it’s easy to understand why he rejects the American dream as a malicious, racist lie. He’s lived that violence, and when he ends his book observing the boarded up buildings, beauty shops, churches, and liquor stores, and rain coming down in sheets—anyone who lives in this city sees these things every day, and you’d have to be a complete dolt not to connect the dots. At least Brooks leaves himself open to criticism, unlike the disgusting fawning from the left for this book, the kind of praise that absolves them of responsibility and accusations of racism and ignorance. For once, Brooks actually licks the humble pie that covers his face.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992